On a small side street off Tel Aviv’s famed Rothschild Boulevard stands a seemingly insignificant house. As humble as the man who was once the owner, the building’s unpresuming exterior is wholly unrepresentative of the amazing story within it.

Inside the 53-sq.m. studio is a colorful array paintings, portraits and photographs. Bookshelves hold personal narratives, and homemade structures tell the story of creativity, humor and love for theater.

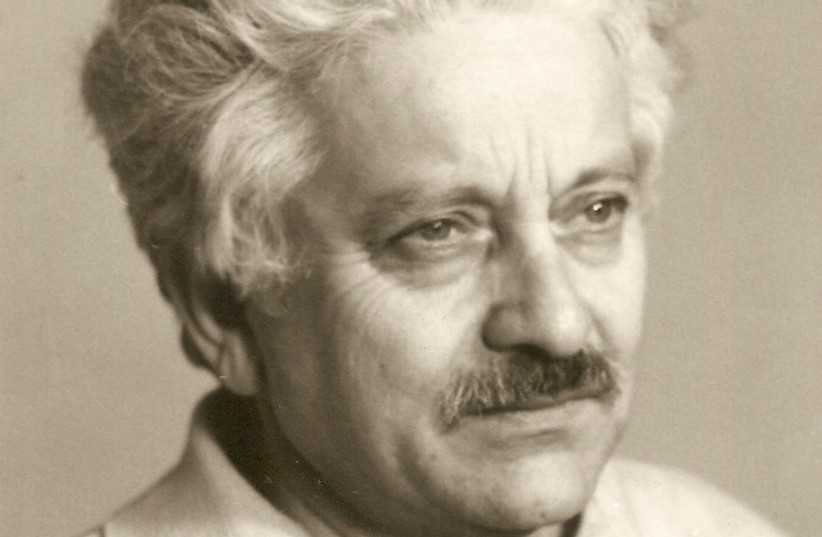

This small museum contains the entire life story of Joseph Bau, one of the first graphic artists in Israel.

One of Israel's first graphic artists

Bau built the studio in 1960, two years after arriving in Israel from war-torn Krakow. Having studied design in his early years in Poland, his dedication to art was interrupted by the outbreak of World War II.

It was this very love of art that saved his life, explained daughter Clila Bau, owner and director of the museum. During his first year at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow, Bau’s calligraphy teacher announced an optional lesson in German Gothic letters. Bau was the only student who decided to attend.

When Bau and his family were taken to the Krakow ghetto, the Nazis were looking for someone who knew how to write Gothic letters, and he was the only one. So he began working for the German police while simultaneously using his skills in letter-making to forge documents for the Jewish underground.

“The funny thing is that the Nazis were looking everywhere for spies, and they didn’t know that the biggest spy was sitting right in their office,” laughed Clila.

Bau’s two daughters, Clila and Hadasa, have been running the museum for 25 years in hopes of continuing their father’s legacy. However, they are at risk of shutting down the museum that has kept their father’s memory alive for years.

“My parents’ heritage will disappear if we close. We are petrified. Such an important story, such an important museum… you don’t have a museum like this anywhere else in the world,” Clila said.

“My parents’ heritage will disappear if we close. We are petrified. Such an important story, such an important museum… you don’t have a museum like this anywhere else in the world.”

Cilia, daughter of Joseph Bau

Bau, the Holocaust and Schindler's list

BAU’S 13-year-old brother had already been killed in the Krakow ghetto when Bau he was taken to the Paszow concentration camp, along with his parents and his other brother. There, Bau met Rebecca Tennenbaum, a nurse who served as the manicurist of Amon Goeth, commander of the concentration camp.

Dressed as a woman, Bau smuggled himself into the women’s barracks. With two rings fashioned from a small silver spoon he had traded his bread rations for, he married Rebecca, whom Clila described as “the strongest woman she’s ever known.”

Following the release of Stephen Spielberg’s famous film Schindler’s List, people from all over the world flocked to interview the couple, dubbed “the most romantic couple ever.” But it wasn’t only love that motivated the young pair to marry, according to Clila.

“They got married from love but also to give other people hope. To show them that life will continue,” she said.

Just as her father, Clila remembers her mother as a hero who saved many lives during the Holocaust. Rebecca knew nine languages and would return to the barracks to warn women of news she had heard from the Nazis as she tended to them.

“One day my mom heard they were making a list,” Clila recalled. “It ended up being Schindler’s list.” She recounted that Rebecca convinced one of the men compiling the list to write her husband’s name instead of hers.

“My mom went to Auschwitz and my father to Schindler’s camp. She didn’t tell my father [about it] for 50 years because she did it out of love. She didn’t want him to feel like he owed her anything.”

A cartoonist in Poland, writing on the Holocaust with humor

Following the war, the couple moved back to Krakow, where Bau continued studying design. He became a renowned caricaturist and designed cartoons for four newspapers.

“My father was very successful in Poland,” Clila explained. “But he never told us any of this because he was always so humble. We would tell him, ‘You are a genius,’ and he would always respond, ‘No, I’m just a simple painter.’ I learned most of these things from my mother’s diary.”

However, Bau was anything but a simple painter. “He was an author, and a poet, and a painter, and an animator, and a graphic designer. And he was a photographer, and he was the best father and the best husband. I can go on and on and on because he was multi-talented,” Clila said.

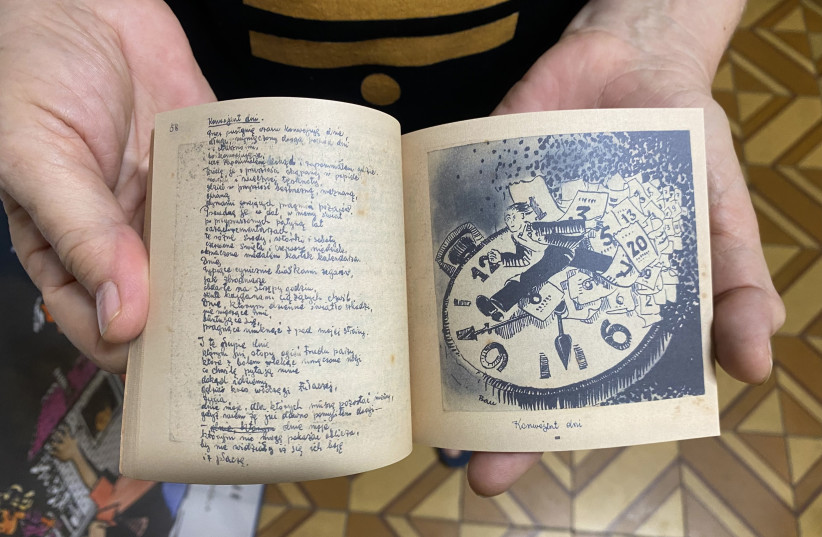

The author of 10 books, Bau had a fascination for the Hebrew language. In Brit Milah, he explores the logic and humor of the Hebrew language, often portrayed through amusing cartoon drawings. His most well-known book, Dear G-d, Have You Ever Gone Hungry? narrates his experiences in the Holocaust with a collection of poems, memoirs, sketches and, most importantly, humor.

“He never lost his humor. Even in the most difficult moments, he would find something funny to say,” Clila recounted.

Bau received plenty of criticism for writing about the Holocaust with humor, according to his daughter. But that was his way. “In the most horrible situations, he used to say something and poof, everyone would laugh,” she said. “This is a huge talent. It was his own unique style of humor. Black humor, but humor none theless.”

Moving to Israel

AS BAU began to feel a tighter control over what he could and could not publish in Polish newspapers, he decided in 1950 that it was time to move to Israel. He became one of the first graphic artists in the country and began designing fonts for many famous movies.

“For each movie, he made special letters. And when someone came here and said, ‘Bau, you made such beautiful fonts, can you design the same for my movie?’ My father would say, ‘Close the door on your way out. I never do the same thing twice.’ He was full of ideas. As we say in Hebrew, ‘They came out of his sleeve,’” Clila said

In 1960, Bau had the idea of creating his own animation studio. Clila recalled that when her father told Rebecca that he wanted to build his own studio, she responded, “But we don’t even have money for food.” He replied by saying that it would be no problem because he would build everything by himself. And he did.

Bau’s unique creations are showcased in the museum today, including the world’s smallest movie theater, according to Clila.

There’s a sewing machine made from an engine and parts from the family’s kitchen. Also, there’s an animation table made from the arm of an old X-ray machine. And, most eye-catching, a drawing of a naked Bau above the sink with two bars of soap hanging below, which he instructed his daughters to add.

However, the artist’s animation studio is not everything it seems to be. “For a while, my sister and I thought that our father was simply an artist,” Clila explained. “But one day, there was an exhibition in the Knesset, and our father was featured there. That is how we found out that he was the main graphic artist for the Mossad.”

Bau forged documents for the Mossad, the national intelligence agency of Israel, and its spies. He even made the papers for Eli Cohen – the famed Israeli spy who was caught in Syria and hanged in May 1965 – and the team that caught Adolf Eichmann in Argentina.

“My father lived a double life, and his studio was a cover for his activities,” Clila said.

The Joseph Bau House Museum

ALTHOUGH BAU’S studio now bears the name the Joseph Bau House Museum, it is not officially considered a museum, his daughter explained. “According to the authorities, we have to be 200 sq.m. to be officially considered a museum. We are only 53.”

Because of this, the museum does not receive public funding, and Hadasa and Clila have struggled to keep the museum’s doors open.

“They are going to tear the building down and kick us out. And we don’t want that,” Clila said.

What the closure of the museum could entail, however, is more than the memory of Joseph Bau – it also comes with a big loss in Holocaust remembrance.

Today, if you go to the place where the Plaszow concentration camp once stood, you see nothing. Poles can be seen riding bikes and playing ball, recalled Clila from her visit to Krakow.

Part of Bau’s inspiration for his novels came from his goal of continuing a dialogue about the Holocaust. “That’s why my father wrote his books with humor,” Clila explained. “Usually people are afraid to read about the Holocaust because it’s hard to do. But my father wanted many people to read about his experiences. And he succeeded greatly.”

For Clila, it’s difficult to understand why the Culture Ministry refuses to support her father’s museum. The COVID-19 pandemic, lack of public funding, and overall absence of advertisements have left the two daughters unsure about the future of Bau’s animation studio. “If someone will give us money, we will even name the museum after them,” Clila laughed sadly.

“If we don’t talk about the Holocaust and you don’t talk, what will happen? In a couple of years, someone will come and tell me that the Holocaust didn’t exist. You can see it in my father’s drawings,” she said. “He would not like us to be bystanders like the chess pieces in his painting.” ■

To learn more, visit: www.josephbau.com/?module=category&item_id=26 www.causematch.com/en/josephbauhouse/