"I was so lucky to work with my father,” says Nadav Lifshitz, youngest son of prominent Israeli artist Uri Lifshitz.

“My mother was always very much involved with my dad’s work, and I was always close to my father, but during my adolescence we, naturally, had our differences. When I turned 18 we became very close, and during the last six years of his life we worked together in the studio. It was wonderful,” says Nadav, an artist in his own right.

Uri Lifshitz (1936-2011) grew up in Kibbutz Givat Hashlosha. His early work was characterized by a lyrical abstract style. In the early 1960s, he changed directions to figurative art. Lifshitz never received formal training but studied briefly with artist Chaim Kiewe. His works are characterized by postmodern semiabstract paintings with bold and passionate brush strokes.

Lifshitz began painting in the 1950s in the kibbutz. In the 1960s and 1970s he was one of the founders of the “10 Plus” group, which offered an alternative to the lyrical abstract style of the New Horizons (Ofakim Hadashim) artistic movement, the dominant art movement in Israel at the time, with founding members such as Yossef Zaritsky, Avigdor Stematsky and Yehezkel Streichman. Lifshitz participated in the last New Horizons exhibition.

The Uri Lifshitz building, located in the south of Tel Aviv, was the artist’s studio for many years and was reopened by Nadav and his mother, Dorit Lifshitz, as a home for his artistic bequest, an exhibition space and research archive.

New exhibition, 'In favor of illusion' offers new perspective

A new exhibition there, “In favor of illusion,” offers a new perspective of the beloved artist’s work, both in the way it looks at itself and the way it relates to artistic trends in Israeli and international art at the time, as well as toward other arts, such as literature.

“My father used to refer to himself as a historical painter. He was always connected to expressive, figurative and even pop art sometimes. But he associated himself with a genre of painters from Da Vinci to Goya and Velazquez."

Nadav Lifshitz

“When we opened this house, the decision was to begin at the beginning, to start from something that already exists. And we chose his one-man show at the Helena Rubinstein wing of the Tel Aviv Museum in 1973,” Nadav says, showing works stored in their archive, including some rare sketches and etchings from the artist’s early years. “It was of the utmost importance for us to place the project in its historic context. It was his first big show, and it was our opening exhibition here. The works were also his first using his projection technique, so really you can look at them as the works with which he defined his art, his painting.”

“Visiting this house, where Uri worked and created his art, allows visitors to really delve deep into his art, his creative process,” says Dorit Lifshitz. “It took a lot from us both. In the last two years, Nadav put everything else, including his own art, aside, and we dedicated every moment to creating this center. Difficult? It is a lot of work, but when you do something you really believe in, something that is so close to our souls, it makes it easy.”

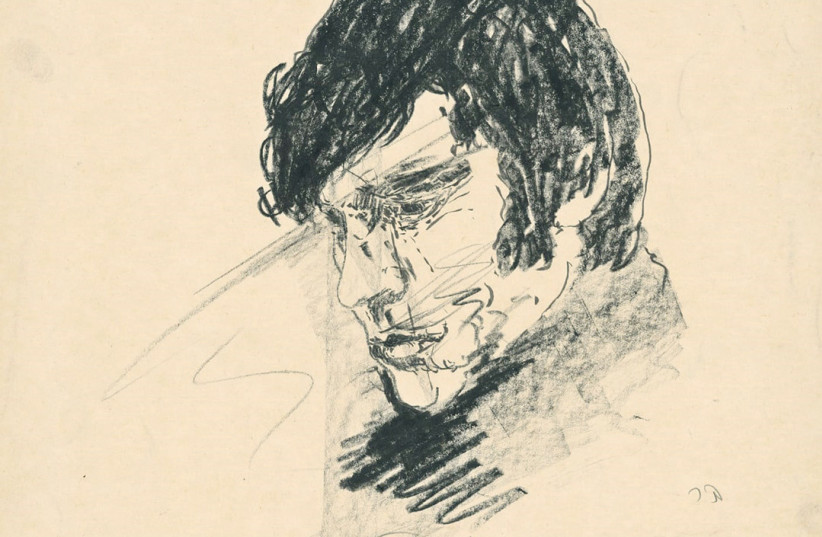

THE NEW exhibition has two points of departure: the first is a portrait of poet Yotam Reuveni (1949-2021), created by Lifshitz soon after Reuveni’s first book, In Favor of Illusion, was published. The second point of departure is a drawing which represents the transformation of the artist from abstract personal painting to figurative nonpersonal art, in which the physical body is removed and reappears as an image, a memory.

The exhibition includes about 20 large-scale oil paintings, as well as many small-scale drawings on paper.

“This is our third exhibition since we opened the center,” says Nadav. “This used to be his studio; here, he worked. Since he used projection, the windows were always covered. The space was open and crowded,” he says. “There were heaps of works, canvases, paint.

“We decided to turn the studio into the exhibition space,” says Nadav showing me the top floor. “We left the walls exactly as they were. It was important for us to keep the dialogue with the history of the building, too. After 1948, the building became industrial, so you can still see where the pipes went. We didn’t cover it. We wanted the layers of the history to show.

“My father used to refer to himself as a historical painter. He was always connected to expressive, figurative and even pop art sometimes. But he associated himself with a genre of painters from Da Vinci to Goya and Velazquez. They were his pertinent group, so to speak. Later, he also took historical and current events as subjects for his works. He painted large-scale portraits, hundreds of them. Many were of public figures, actors, artists....” continues Nadav.

“While going through the works, I stumbled upon a portrait of the late Israeli writer and poet Yotam Reuveni. This portrait is different. It is much smaller than the other ones, but also different in other aspects. He usually painted people looking forward, en face. Reuveni’s portrait is a profile. I didn’t know much about Reuveni. I found his first book, In Favor of Illusion, a wonderful book. And I found many things that connect between his writing and my father’s art – the relation to one’s body and the body that is being drawn into an imagined world to find an escape from the real world, the real body.

“Father suffered from a heavy stutter since his early childhood. Communicating was very difficult for him, and he was a very introverted child. He felt that art was a way to reach out to the world, but the abstract painting kept him locked inside. He believed that the way for him to communicate with the world went through the body; not his own body, but through painting and drawing the human body – meaning, through figurative art.”

For Lifshitz, schizophrenia meant the battle between his inner world and the outer world, a battle he experienced constantly since his childhood in the kibbutz, his relationship with his mother.

“He was called Uri after a sister that passed away, and his childhood was tainted by this tragic event. He wanted to go out of his body, which he experienced as damaged. He wanted to free himself from his traumatic army experience [Lifshitz was a soldier in the famous unit with Meir Har-Zion and Arik Sharon]. He believed the figurative art would save him,” continues Nadav. “He always started with some abstract and then developed the figure from that. The Schizophrenics was also the first time he used text as part of the art.

“The transformation to figurative drawing started first in small, sometimes blunt, sketches – sexual scenes, severed body parts. But you have to remember that at the same time he was still painting abstract. But the figures kept bursting out of him, together with texts written in mirror writing. He found his escape.”

Participating in group exhibitions, Lifshitz met Igael Tumarkin, and they immediately became friends.

“Their place in the Israeli art world is similar, and they really appreciated each other,” says Nadav. Tumarkin introduced Lifshitz to Shaya Yariv from Gordon Gallery. Yariv came to see the works in the kibbutz and bought everything at once. “He literally bought everything that was in the studio, some 1,000 works, including oil paintings, sketches – everything. The two signed a life contract and became brothers. They really loved and respected one another. My father also had a close relationship with Helit, Shaya’s wife, and her father, the poet Avoth Yeshurun, who later wrote a poem about Dad,” smiles Nadav.

That was at the end of the 1960s, and suddenly Lifshitz saw a way out. He, of course, shared his new fortune with the kibbutz and his wife, and then accepted Amos Kenan’s invitation to join him in Spain.

“My father used to describe it as an amazing experience. He landed in Madrid and stopped stuttering. Just like that. He was 30, and he stuttered all his life, and there he suddenly stopped. Not only that, his mirror writing disappeared from his drawings, and he started writing normally. Many bodily sensations he suffered from as a child were gone. He used to say that he was reborn. He started to talk. When he returned to Israel, he had a large show with paintings inspired by Goya.”

The new exhibit started with the portrait of Reuveni, explains Nadav. “My father felt connected to many writers who influenced him – people like Adam Baruch and Amos Kenan, as well as others. Reuveni was an outsider. Pinhas Sadeh wrote in the forward of Reuveni’s book that ‘it is not in favor of the illusion, but in favor of the confession.’ I like it. Confessional writing – like Rousseau.”

During the COVID-19 closure, says Nadav, he and his mother found themselves with time on their hands.

“We decided to go ahead with the project,” says Dorit. “It gave us time for self-examination, time to dive into the body of works. It allowed us a different point of view to his creation.

“In the last years of his life, Uri, Nadav and I were together all the time. After his death, Nadav lived here. Nadav lives here, and he told me that he tiptoes around because he feels that he is in a holy place. It took time to be able to look at the materials and organize everything. Now all the works, the history and his life story – everything is here. We are building the project and we are patient.

So far, it works well. People come here, as groups or alone; they wonder in, and if they want we give them a tour. They can spend time here looking at works and books in the archive, and it is free. You can order a guided tour, both in Hebrew and in English.”

“The tour depends a lot on the participants,” says Nadav. “I go with what people are interested in.”

Uri Lifshitz House, 2 Abarbanel Street, Tel Aviv, open Thursday, 4 p.m.-8 p.m. and Friday-Saturday, 10 a.m.-2 p.m. Admission is free.