Sylvia Raphael was known in Israel as a Mossad agent who had participated in a whole slew of heroic operations that took place all around the world, the most famous of which was the Lillehammer Affair – a 1973 assassination attempt in Norway on Ali Hassan Salameh, following the murder of the Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics. The operation was a fiasco, since an innocent man was murdered due to an identification error.

A new photography exhibition, which opened a few weeks ago at the Yitzhak Rabin Center in Tel Aviv, 18 years after Raphael’s death, presents a new and lesser-known side of her: her life as a photojournalist, using the cover name Patricia Roxborough, while she worked as a Mossad agent in the Middle East and around the world.

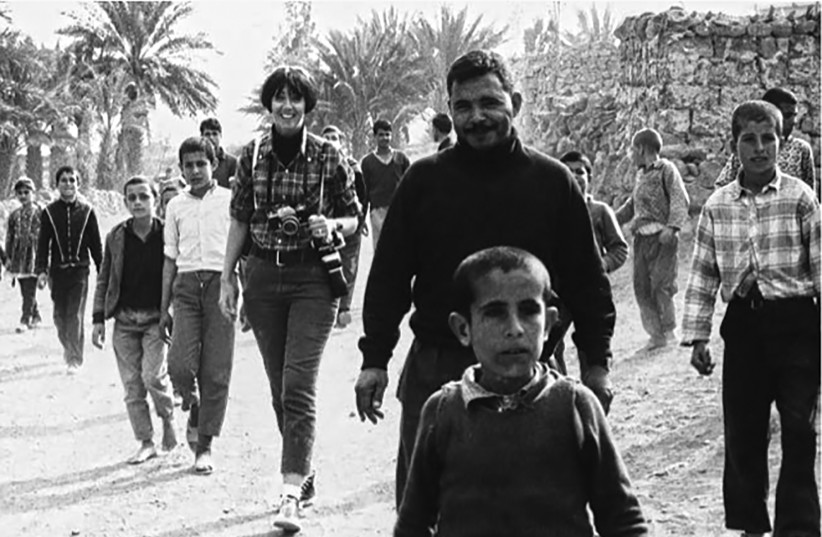

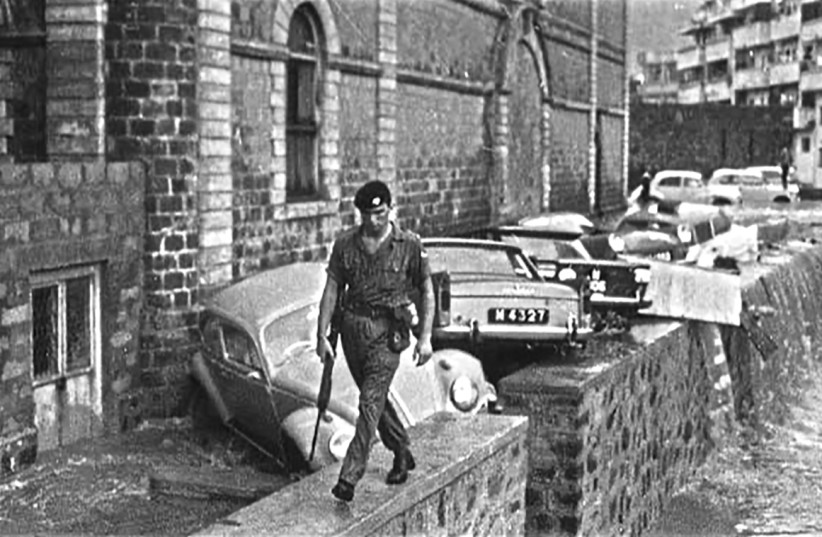

The exhibition displays 47 photographs taken by Raphael in Egypt, Djibouti, Yemen and Jordan, as well as at film sites and cultural events in Paris and the UK. Some of the photos feature images from street protests in Aden, Yemen; a social uprising in Djibouti; and PLO training camps in Jordan. “We’ve also included five photographs of Raphael herself,” explains Ilan Schwartz, the force behind the exhibition, who has been engaged in entrepreneurship and finding technological and logistical solutions in the art world for the past 14 years.

Schwartz first learned about Raphael’s story from a book he read. “My mind kept going back to the fact that she used her cover as a photojournalist to place herself in conflict zones in the 1960s and 1970s. One thing that made me extra curious was that she wasn’t even Jewish – her father was Jewish. She’d grown up in South Africa, and yet in 1963 she’d come to volunteer in Israel on her own. She made a tremendous personal sacrifice.”

Schwartz was incredibly curious about Raphael’s life. In his research, he discovered rare photographs taken by Raphael that had never been seen by the public. “For over eight years, I’d been trying to gain access to this treasure, and finally a year ago I received a green light from Israel’s Prime Minister’s Office.”

Tamar Arnon and Eli Zaguri, the exhibition curators, sorted through all the negatives of photographs taken by Raphael as they prepared for the exhibition. “The idea behind the exhibition was to tell the personal side of Raphael’s life,” Schwartz explains.

“We decided not to focus on her work as a Mossad agent, but instead to show her tremendous contribution to Israel. She was a trailblazer who gave up so much of her private life for the sake of a country that was not the country of her birth. This was the first time the public was being exposed to the artistic side of her amazing story.”

Although she never officially converted to Judaism, Raphael, who was born in 1937, saw herself as a Jew. Her first home in Israel was at Kibbutz Gan Shmuel, and soon after her arrival, she joined the ranks of the Mossad. After training for a year in Canada, Raphael began participating in missions throughout Europe and the Middle East, with Paris as her base.

After the Lillehammer Affair, Raphael and her colleagues were arrested in Norway. At the trial, Raphael was found guilty of aiding and abetting a murder and was sentenced to five years in prison. After negotiations with the Norwegian government, all the Mossad agents were released after serving one-third of their sentence. Upon her release, Raphael married her Norwegian defense attorney, Annæus Schjødt, who’d been hired by the Mossad to represent her. She was deported from Norway, so she returned to Israel with Schjødt and the two of them made their home on Kibbutz Ramat Hakovesh.

In 1978, the couple moved back to Norway, where Raphael devoted her time to volunteering at charity organizations. In 1992, she decided to return to the country of her birth, and so the two of them moved to South Africa, where Raphael lived until her death from cancer in February 2005. In accordance with her wishes, her body was brought back to Israel, and she was buried at Kibbutz Ramat Hakovesh.

CO-CURATORS ARNON and Zaguri, a couple who lived in London for 28 years, are internationally recognized for their work with museums, collectors and private galleries. “This is of course not the first time that an artist’s talents were discovered only after their death,” Arnon says. “We’ve seen this countless times in our work.”

Two years ago, they returned to Israel, met with Schwartz and began sketching out their plan for the exhibition. “I knew who she was right away, but we had no idea that we’d end up spending thousands of hours working on this project. We loved Raphael’s interesting photographs from the start, but nothing could have prepared us for what we would encounter later on.”

What did you discover?

That Raphael was a fascinating woman, and that every person who met her fell in love with her. A good photographer needs to be able to make people feel comfortable, and sometimes to even take an active role in the filming. Raphael was skilled at all of this. People loved her – it didn’t matter if the subject was an Arab sheikh or a Bedouin in his tent or a Hollywood star in Paris. She understood how to skillfully break the ice with everyone.

How did this affect her photographs?

One of the most uncommon aspects of her photographs is that she didn’t just take photographs of these individuals – oftentimes she would appear in some of the photos beside them. Usually, the photographer remains behind the camera, but because of her outgoing personality, sometimes she would turn the camera around. That is what makes this exhibition so distinctive. We were not aware of this when we began our research.

The 1960s and 1970s were the golden age of photography, especially photojournalism, and photography exhibitions in museums were quickly gaining popularity. “Raphael began working at a time when photography was first becoming recognized as an important art form,” Arnon continues. “Stories about Mossad adventures and the operatives carrying them out were very exciting; but as an art curator, my goal was to show her talent as a photographer. She could very well have been Annie Leibovitz, for example, if she had chosen photography as a career instead of as a cover story.”

THROUGH THE photographs on display, it is clear that Raphael’s life as a photographer and as a Mossad agent blended seamlessly. She went on trips to numerous countries in Africa and the Middle East, for which she was sent by a French photo agency. She also covered Hollywood stars and was able to get shots of famous movie stars like Yul Brynner, Danny Kaye, Eli Wallach and Brigitte Bardot. “At first, we only saw photographs she’d taken in the Middle East, but apparently her talent had been obvious to her bosses, since she was sent to cover movie sets and stars. While we were looking through all the negatives, I couldn’t believe how many legendary movie stars she’d encountered.”

"While we were looking through all the negatives, I couldn’t believe how many legendary movie stars she’d encountered."

Tamar Arnon

According to Arnon, one of the biggest challenges in creating this exhibition was in the restoration process. “We were tasked with restoring photographs that had completely faded, and working with negatives that were in pretty bad shape. Luckily, we had access to a software that was immensely helpful, which we would not have had at our disposal had we undertaken such an exhibition, say, twenty years ago. We received help from people who specialize in this type of restoration.”

“For hours we sat bent over looking at negatives with a magnifying glass while we tried to discern what we were seeing,” added Schwartz. “When you suddenly realize that you’re looking at an image of Danny Kaye when he was like 38 or 40, you have to stand back for a second and rub your eyes before believing that’s who you’re actually seeing.”

“It was incredibly exciting tracing the path she’d taken, especially in her early years,” Arnon explains. “Slowly, we began to grasp the path she’d taken, and what her thought process might have been. We discovered that she was a strong, independent woman who knew how to connect with people. All of these skills helped her turn out to be an excellent Mossad agent. It was important to us as curators to present her as a woman who was worthy of admiration for her artistic talent as well.”

In one of the historical photographs, Raphael is pictured standing just a few meters away from Anwar Sadat and Gamal Abdel Nasser. “She came as close as possible to the important leaders of the era,” Arnon continues. “She was in Yemen during shelling. She hid under a car but continued taking pictures. She was so courageous. Nowadays, war photojournalism is a profession, but very few women choose this career. And she did this 50 years ago, in the Middle East and Africa, without any fear.”

“The Middle East is a very male-centric place, and it’s crystal clear where women are situated within the hierarchy,” adds Schwartz. “And then you see the photographs of Raphael in the 1960s as she walks around inside refugee camps in Jordan, with a huge smile on her face, surrounded by men and children. No one is bullying her, and she does not appear frightened. She radiated a special feeling to the people around her. As if she was trying to tell them: ‘I’m here. I’m part of you. Don’t be afraid.’ She didn’t walk around with bodyguards, an escort or a technical assistant. It was just her, and she did everything on her own. That’s why she was able to create such intense feelings of intimacy with the people she photographed.”

Translated by Hannah Hochner.