Throughout 2014, US secretary of state John Kerry worked around the clock to get talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority off the ground. Kerry was representing president Barack Obama, and the two of them believed that the time was ripe for brokering a historic peace agreement and that the founding of an independent Palestinian state, with the Green Line as its border, would make it possible for the two nations to make peace with each other.

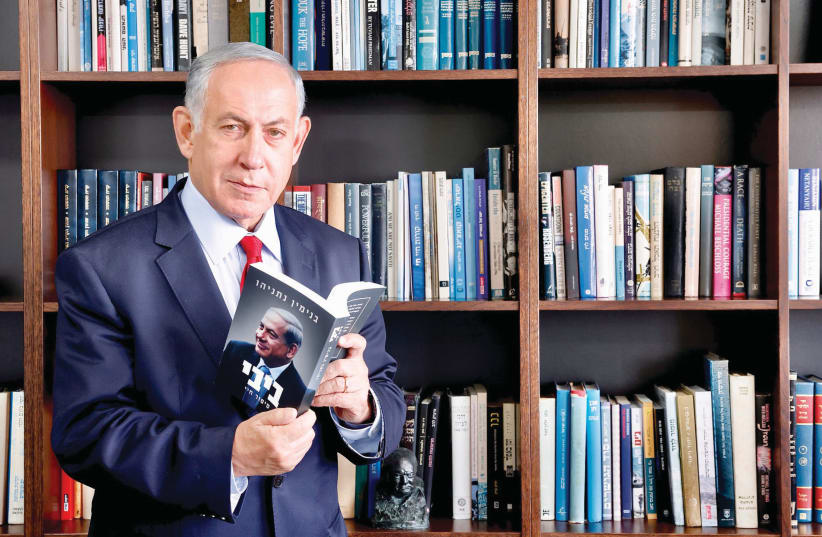

In his new book, Bibi: My Story, Benjamin Netanyahu provides a detailed exploration of how throughout the Obama administration, he worked fervently to thwart the creation of an independent Palestinian state.

That same year, three Israeli teens were kidnapped at the Gush Etzion intersection, and a few weeks later, Israel found itself immersed in a fierce war with Hamas in the Gaza Strip. Throughout Operation Protective Edge, ministers Avigdor Liberman and Naftali Bennett demanded that the IDF send forces into the Gaza Strip in an effort to overcome the Hamas leadership. Netanyahu refused unequivocally to even consider this option. In his book, Netanyahu describes how he withstood the pressure to upgrade the military operation into a full-scale war in the Gaza Strip with the goal of overthrowing the Hamas regime.

These two events took place concomitantly during that period: Israel was feeling international pressure to withdraw from the West Bank, as well as domestic pressure to send IDF ground forces into the Gaza Strip. Netanyahu takes pride in the fact that he managed to fend off this pressure from both sides. He managed to refrain from setting off on a political adventure with Obama and Kerry, and also from going out on a military adventure with Liberman and Bennett. Netanyahu succeeded in holding back from making peace and also from making war.

This doubly cautious behavior – refraining from both military and diplomatic activity – is typical of Netanyahu’s behavior throughout his political career. His double caution led to disappointment for those who believed in the power of diplomatic agreements to heal reality, as well as for those who believed in the power of military operations to achieve this healing.

People on both sides believed that Netanyahu’s refusal to engage in bold actions that would mold a new reality meant that Netanyahu was giving up on his ideological goal. His detractors were not always aware that this double caution was not a result of his sacrificing his beliefs, but instead was the result of his full realization of them.

What are Netanyahu’s beliefs?

In his autobiography, Netanyahu outlines the vision that has guided him during the years he was the finance minister and prime minister: “There is no longevity guarantee in the life of nations,” Netanyahu declares. In his view, the destruction and annihilation of a country are in the realm of real possibility. Moreover, Netanyahu claims that exalted values do not guarantee the survival of a nation: “Being a moral people will not save you from occupation and massacre.”

“Being a moral people will not save you from occupation and massacre.”

Benjamin Netanyahu

“Being a moral people will not save you from occupation and massacre.”

According to Netanyahu, the only way to guarantee the continued existence of the Jewish people is by transforming the State of Israel into a country with exceptional capabilities and strengths. One of the prerequisites for this formula for building up a strong Israel is economic success, since this would enable the country to acquire military capabilities. The combination of economic power with military power results in diplomatic power. According to Netanyahu, these three powers, when bound together, will ensure the survival of the State of Israel.

For people who grew up espousing the values held by Israel’s Labor movement on the one hand, or alternatively by Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, this vision seems weak and watered down. In fact, for ideologues from Labor or the Religious Zionist movement, it is even difficult to call Netanyahu’s worldview a vision. According to Berl Katznelson, the socialist-Zionist movement’s great ideologue, the State of Israel has a lofty purpose: to establish a model socialist society that will be a light unto the nations. For Kook, the religious-Zionist’s great ideologue, the State of Israel has a lofty purpose: to revive the prophetic spirit and pave the path to the redemption of humanity.

So according to Netanyahu, what is the purpose of the State of Israel? The very existence of the state is its objective. This is conservative thinking in the literal sense of the word. This is the source, among others, of Netanyahu’s double caution: caution of peace and caution of war. After the exile ended, the State of Israel became a fait accompli. The goal of a Zionist leader, according to Netanyahu, is not to alter reality but to preserve it.

Netanyahu’s conservative vision has deep roots in the history of Zionism. Ze’ev Jabotinsky was opposed to all attempts to add any additional values to Zionism. Social Zionists tried to add social values to Zionism, and Religious Zionists tried to add religious values. Jabotinsky called these attempts shatnez [literally, cloth containing both wool and linen, which is forbidden by Jewish halachic law]. Jabotinsky advocated for monism.

If monotheism is the belief in one God, monism is the belief in one value, and for Jabotinsky that one value was Zionism. The State of Israel is not a means to attain a great ideal, the state is the great ideal. The state is the goal, not the means.

NETANYAHU LEARNED about Jabotinsky’s monism from his father, historian Prof. Benzion Netanyahu. Throughout the book, Netanyahu describes his relationship with his father as similar to the relationship between a student and his teacher, or even like the relationship between a devotee and a hassidic leader. Netanyahu accepts his father’s ideology without any reservation, criticism or questioning.

This is what the chain of transmission looks like according to Netanyahu: Netanyahu the elder was a devoted student of Jabotinsky, and Netanyahu the younger was a devoted student of his father. Between Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the founder of the Revisionist Movement, and Benjamin Netanyahu, the current leader of this movement, there is only one person.

This rare situation is apparently a one-off occurrence. Between Bezalel Smotrich, for example, and Rabbi Kook, there are at least four mediating figures: Smotrich’s rabbis are students of Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, the son and student of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook. Between Merav Michaeli, the current leader of the Labor Party, and David Ben-Gurion; or between Zehava Gal-On, the current leader of the incarnation of Mapam, and Yaakov Chazan, there are many more links.

However, between Netanyahu and Jabotinsky, the connection is almost direct – just one person separates the movement’s founding leader from the current leader who is realizing the movement’s goal.

Netanyahu the elder, however, did not pass this tradition on to his son in a neutral way. Netanyahu the elder did not just pass on Jabotinsky’s legacy – he interpreted it, reshaped it and expanded upon it. According to Benzion Netanyahu, the existence of the Jewish people is not guaranteed. The people of Israel are not an eternal people, and it is possible that they could become extinct and disappear from the face of the earth.

In his 1993 book A Place Among the Nations, Netanyahu gives expression to his father’s spirit, which asserts that after the Holocaust, the Jewish people could have become extinct and disappeared. “At the close of World War II, it was not clear at all that the Jewish people would survive… After four millennia of unparalleled struggle for their place under the sun [the Jewish people] would have finally yielded to the forces of history and disappeared.”

According to both father and son, the Jewish people are in a precarious state. Just like what happened to other nations, like the Girgashites and the Jebusites, the Acadians and the Sumerians, the Jewish people could also disappear. This is why the State of Israel has such great historical importance. “The State of Israel is not only the repository of the millennial Jewish hopes for redemption,” Netanyahu writes, “it is also the one practical instrument for assuring Jewish survival.”

This is how the survival of the Jewish people became the objective of the State of Israel. Only someone who agrees that the existence of the Jewish people is fragile and that its continuity is not self-evident can empathize with the vision of the Netanyahu family. But not everyone agrees with this. In fact, according to Benzion Netanyahu’s creed, the original sin of the Jewish people is their lack of awareness of the existential threat that is always lurking around the corner.

The ultimate aim of every creature is to protect itself, and each organism acts instinctively out of self-preservation. Animals develop sharp senses that provide them with advanced warning of threats, which in turn enables them to escape danger. Benzion used to say that even insects can incredibly, quickly, identify a hand that is about to swat at them, giving them time to escape. Not only do healthy organisms have these natural and healthy senses, but so do healthy nations. And yet, the Jewish people is not a healthy people, Benzion Netanyahu alleged.

Benzion Netanyahu engaged in research about Don Isaac Abravanel and valued his writing greatly. And yet, he still considered Abravanel to have failed as a leader. Why? The reason is that despite all the warning signs that foreshadowed the impending disaster that was closing in on the Jews in Spain, Abravanel didn’t recognize them and did not warn the members of the Jewish community of the approaching dangers.

And if Abravanel is the anti-hero, then who, according to Benzion Netanyahu, is the true hero? Netanyahu the elder identified two heroes: Theodor Herzl and Ze’ev Jabotinsky. In contrast with Abravanel, Herzl and Jabotinsky successfully foresaw the impending disaster.

Decades before World War II, Herzl predicted that European Jewry was facing annihilation. Years later, Jabotinsky traveled around Europe, giving speeches to indifferent and naive audiences that failed to understand how precarious their reality really was. He hurled prophetic words at them describing this reality in detail: “I’m warning you, a catastrophe is swiftly hurtling toward us… You fail to see the volcano, which at any moment will erupt and begin emitting the fire of destruction.”

Benzion Netanyahu developed a unique and interesting talent for judging historical figures. The hero is measured by how well he can foresee the future and recognize the catastrophe that is just around the corner. By this standard, Jewish history is full of failed heroes.

ONE OF the most prominent characteristics of Zionist writing is criticism of the Diaspora Jew. Zionist thinkers are all in agreement that the personality of the Diaspora Jew is flawed, and their only dispute is the question of what exactly these flaws were.

According to Katznelson, the Jewish people lost their productivity while in exile; according to Ben-Gurion, it lost its statehood; according to A.D. Gordon, it lost its connection with nature; according to Rabbi Kook, it lost its connection with the spirit of prophecy. According to Benzion Netanyahu, while in exile the Jewish people lost their instinct to identify existential danger.

Among all of the ideas espoused by Netanyahu the father, this is the concept that had the most dramatic influence on Netanyahu the son. Similar to Benzion Netanyahu, Benjamin Netanyahu also examines and judges the greatness or insignificance of historical figures according to the question of whether they are capable of recognizing and predicting catastrophes. Again, this is an original and unusual benchmark to use for measuring the greatness of historical figures. In the Netanyahu family, a leader is not judged by what he built but by what catastrophe he prevented.

For our purposes, this is a very important point, since this is the yardstick by which Netanyahu measures the success of his own career. Throughout his autobiography, in which he summarizes his life’s work, Netanyahu describes again and again how he foresaw impending disasters and issued warnings accordingly.

He is the person who in 1993 identified the dangers of the Oslo Agreements; who in 2005 foresaw the dangers of a unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip; who in 2011 predicted the dangers inherent in the Arab Spring; and, of course, above all, he is the one who warned the world of the great danger a nuclear Iran poses for the State of Israel. The narrative goes like this: The father identifies the problem, and then the son implements the solution.

According to Netanyahu, this chain of transmission does not begin with Jabotinsky but with Herzl. Jabotinsky is the successor of Herzl, Benzion is the successor of Jabotinsky, and Bibi is the one who finally brings this glorious tradition to fruition. There is much truth in this. Herzl did indeed predict the future. He foresaw the coming extermination of European Jewry and understood that the solution was to create a state that would prevent the annihilation and guarantee the continued existence of the Jewish people.

And yet, Herzl had another side. He believed that a Jewish state was not an end in and of itself. Herzl wrote that a Jewish state was a means that would uphold values that were greater than the state itself: “And I truly believe that Zionism would not cease to be the ideal, even after we obtain statehood in the Land of Israel. Because Zionism, as I understand it, is not only the aspiration to acquire a plot of land that can serve as a safe place for our wretched people but also the aspiration to become a moral and spiritual people.”

Herzl authored two books about Zionism: In 1896 he published The Jewish State, and in 1902 he published Altneuland. These two books are quite different from each other, both in their nature and with regard to the vision they espouse. The Jewish State is an action plan, whereas Altneuland describes a utopia.

Antisemitism is at the heart of the first book, and the concept Herzl presents in it is simple and sharp: The Jewish state is the solution to hatred of the Jews. In contrast, in Altneuland, Herzl writes that the problems Zionism will solve are not just connected to Jews but to all humanity. How? Herzl foresees that the state which the Jews will establish will be a country of innovation. In their country, the Jews will create technological and political knowledge that will help all of humanity to solve the world’s ailments and problems.

Herzl’s two books about Zionism cover both aspects of Herzl’s Zionism. In The Jewish State, Herzl writes about how the world is a dangerous and hostile place for the Jews; therefore, there needs to be a state for them to escape to. In Altneuland, on the other hand, he writes that the purpose of a state is not to provide the Jews with a place to hide from the world but rather a place where the Jews can stand firm and from which they can heal the world.

Benzion’s Zionism was the Zionism espoused in The Jewish State, not in Altneuland. The purpose of the Jewish state was to defend itself from the world, not to repair the world, i.e., half of Herzl. And here is where we are offered a glimpse into the difference between the father and the son: In Benjamin Netanyahu’s Zionism, there are actually fingerprints of Altneuland.

Just like in Herzl’s utopia, the State of Israel is indeed a start-up nation, full of innovation and entrepreneurship. And as in Herzl’s utopia, the State of Israel’s technological strength makes it a model for inspiration to the rest of the world. There is, however, a difference here between Netanyahu and Herzl: Herzl believed that fixing the world was the purpose of Zionism, whereas for Netanyahu, Israel’s special status in the world is a means for ensuring the continued existence and survival of Zionism.

For Herzl, the Jewish state is at the service of the Altneuland, whereas for Netanyahu it is exactly the other way around. For him, the Altneuland was designed to guarantee the survival of the Jewish state.

BENJAMIN NETANYAHU is not passively inheriting his family’s traditional ideology; he’s added a layer of his own to it. Netanyahu’s ideology is a synthesis between Jabotinsky’s alarmism and American capitalism. The Jewish people, according to Netanyahu, has its advantages and disadvantages. Its advantages are its talents; the Jewish people are extremely talented; therefore, it is destined to prosper. Its disadvantage is its naïveté. The Jewish people are naïve; therefore, the Jews are always in existential danger. Netanyahu’s vision is to create a situation in which the virtues of the Jewish people compensate for its shortcomings.

The things that are preventing the Jewish people from breaking out and thriving are excessive bureaucracy, a centralized economy and heavy taxes. Therefore, if we reduce taxes, privatize companies and remove bureaucratic obstacles, according to Netanyahu, the genius of the Jewish people will be free to create an expanding and powerful economy. And a strong economy can support a strong military. In other words, a free-market economy will release Jewish talent, and this Jewish talent will create the power needed to compensate for the naïveté of the Jewish people. In short, capitalism is the answer to alarmism.

Indeed, throughout his book, Netanyahu expresses pride in two basic elements: He is proud that he was able to identify the dangers before anyone else, and he is proud of the economic reforms he initiated and led, which were meant to help everyone in Israeli society. According to the Netanyahu paradigm, the State of Israel is not surviving in order to thrive. The opposite is true – we need to thrive in order to survive.

This reversal is the result of the existential condition the Jewish people have found themselves in. The existence of the Jewish people is standing on shaky legs, and that is why we need to mobilize our genius and prosperity in order to not disappear from the face of the earth. According to Netanyahu, the Jewish people are the only nation that needs to demonstrate genius in order to achieve normalcy.

Bibi’s brother Yoni had been slated to be the political leader that would emerge from the Netanyahu family. He was destined to be the figure that would bring his father’s dreams to fruition in the Israeli political arena. At least this is what is expressed in the various biographies written about Netanyahu. According to the conventional narrative, Bibi was Yoni’s replacement. Bibi was the default choice, the one who took the leadership role upon himself after the eldest son fell in battle.

In his book, Netanyahu deflates this narrative with sophisticated literary finesse. The book opens with a dramatic scene in which Benjamin Netanyahu, along with his fellow combat soldiers and his commander Ehud Barak, overtake a Sabena airplane, kill the terrorists and rescue the hostages. Just moments before the military operation is set to begin, Yoni approaches Bibi and asks him to fill in for him.

This is not the first time that Yoni had requested that Bibi replace him. When Uzi Yairi, commander of the General Staff Reconnaissance Unit, recommends that Bibi begin the IDF officers’ training course so that afterward he can return to his unit as an officer and unit commander, Bibi considers doing so and presents this dilemma to his older brother.

During this conversation, Yoni makes a strange suggestion to his brother: “Tell him I’ll take your place.” Yoni’s suggestion is accepted, and that’s how Yoni ends up in the General Staff Reconnaissance Unit. This decision made by Bibi, the younger brother, is what led to his big brother Yoni joining that unit. As we know, Bibi later completed the IDF officers’ training course and remained in the unit. Nevertheless, the reason Yoni joined the General Staff Reconnaissance Unit at that time is that Yoni requested to switch places with Bibi.

Throughout the book, Netanyahu reiterates how much he admired his brother Yoni. There are two times, however, in which he explains that this admiration was bidirectional. In a letter Yoni wrote to his girlfriend, he said the following about Bibi: “I think he is the person I love most in the entire world.” A close friend of Yoni’s told Bibi about a conversation he’d had with his older brother in 1968, in which Yoni spoke about his younger brother in an almost prophetic manner: “He spoke about you with such admiration and love. I’ve never seen such a strong love between a person and their younger brother. Yoni chuckled and then said that one day you’d be prime minister. He didn’t go on to explain what he meant, and I didn’t ask him to.”

According to the narrative Netanyahu builds in his book, the reality is the opposite of how we’re used to imagining it. Bibi is not the one who replaced Yoni; in fact, it is Yoni who tried a few times to take Bibi’s place. And when Bibi took on the leadership position of the country, it wasn’t in place of Yoni but instead was the realization of Yoni’s dream.

AUTOBIOGRAPHIES usually contain two components: events and relationships. The narrator chooses the central events that impacted the direction his/her life has taken and the meaningful relationships that shaped his/her path, and then weaves them together to form a narrative.

Bibi: My Life Story covers all the significant events that took place during Netanyahu’s life, starting with his childhood, in which he interacted with some of Jerusalem’s greatest intellectuals; his teen years in the US; his IDF military service; his university studies; then onto diplomacy and finally politics. The book also answers the question of what were the most important relationships that shaped his character and the path he took in life.

Many of the people who have spent time dissecting Netanyahu’s character refer to the existence of a human triangle with three vertices: Sara Netanyahu, his wife; Yair Netanyahu, his son; and Benjamin Netanyahu. In the various writings about Netanyahu, it is commonly accepted that the internal dynamics of this human triangle are the key to understanding Benjamin Netanyahu’s political behavior.

This book, on the other hand, presents readers with an alternative human triangle that includes Benzion Netanyahu, his father; Yoni Netanyahu, his older brother; and Benjamin Netanyahu. The internal dynamics of this triangle do not, however, explain all of Netanyahu’s political behavior but do help clarify Netanyahu’s vision, which then leads to the ideological decisions he makes throughout his career.

In his early years, Netanyahu moved between his genius father and his heroic brother. When he was a child, he lived overseas with his parents, which was necessitated by his father’s career. He returned to Israel just before the Six Day War in order to reconnect with his brother. He pursued academic studies under his father’s guidance but aspired to have a meaningful military service in the IDF, following in the footsteps of his older brother.

Netanyahu was informed of Yoni’s tragic death when the phone in his apartment rang on July 4, 1976. It was his younger brother, Iddo, calling to tell him that Yoni had been killed. Netanyahu, who had been living in Boston at the time, took it upon himself to travel to his father and mother to give them the devastating news in person.

The long drive from Boston to Ithaca, in upstate New York, was described by Netanyahu as “the seven longest hours of agony.” This trip plants a painful and powerful image in the minds of the reader: Once again, Netanyahu finds himself between his brother and his father, and this time under the most difficult circumstances of all.

The tragedy did not change Netanyahu’s existential experience as someone who is being pushed along by two energetic forces. In fact, one of the most dominant concepts covered in the book is that not only did Yoni’s death not destroy the triangle, but it strengthened the force among the three vertices. It also gave the triangle new meaning: From now on, his goal in life was to continue Yoni’s struggle on the one hand, while simultaneously fulfilling his father’s ideology.

In Netanyahu’s mind, it was possible to carry on with Yoni’s struggle by expanding the war on terrorism in the political realm. Netanyahu founded an institute named after his brother, edited books and organized conferences, all in an effort to create a legacy for Yoni: We must fight against terrorism and never capitulate.

There are numerous examples of Netanyahu’s efforts to fulfill his father’s ideology, but above all in Netanyahu’s mind was the effort to replicate the historical heroism advocated by Herzl and Jabotinsky, who predicted what the future held and warned us to prepare for the impending disaster.

This effort came to fruition in his historic role as the person who alerted the world to the danger of a nuclear Iran. In the days of mourning that followed his father’s death, the main question that occupied Netanyahu was “Did my father truly and sincerely believe that I would succeed in leading the State of Israel in its efforts to thwart the Iranian threat to our existence?”

There’s no doubt that Yoni would have supported Netanyahu in his fight against a nuclear Iran. And yet, from what he writes in his book, it appears that Netanyahu experienced his struggle against terrorism as the continuation of his older brother’s path, and the struggle against Iran as the realization of his revered father’s path. On the face of it, not only was there no conflict or tension between these two struggles, but they actually complemented each other.

And yet, history is full of irony. In October 2011, these two giant struggles to which Netanyahu had devoted his life collided with each other. The moment Netanyahu signed the Gilad Schalit prisoner swap deal and freed more than 1,000 terrorists in exchange for one Israeli soldier was also the moment Netanyahu turned his back on Yoni’s legacy as he himself understood and defined it. How did Netanyahu justify this decision?

In those same days, Netanyahu was trying to gain broad consensus for an Israeli military operation against nuclear facilities in Iran. Netanyahu knew that an operation of this magnitude would require consent from the Knesset cabinet. Netanyahu also knew that opposition to the deal by senior members of Israel’s defense establishment would prevent approval from the political echelon.

The only way out of this imbroglio, according to Netanyahu, was to upgrade his public status: “In order to overcome opposition by the heads of Israel’s security establishment and secure a majority vote in favor of executing the attack, I would have to strengthen my status in the eyes of the Israeli public.”

Netanyahu’s explanation for his conduct regarding the Schalit deal is cumbersome and strange. This is how it is structured: Achieving the release of Schalit will lead to a surge in sympathy for Netanyahu. This sympathy would enable him to receive approval for the military operation from Israel’s political echelon. In other words, Netanyahu was willing to make compromises on terrorism in order to thwart the nuclear threat hanging over Israel.

According to this narrative, in one moment in October 2011, the Netanyahu family triangle collapsed in on itself. When singular historical circumstances put Netanyahu between his brother and his father, Netanyahu chose to follow his father’s path.

The Zionist movement was fraught with divisiveness and discord, but the most important rift of all, according to Netanyahu’s narrative, was not between socialism and capitalism, nor was it between conservatives and liberals, nor between the religious and secular communities. The real divide was between people who were naïve and those who had a realistic understanding of the dangers in the world.

It is quite surprising, then, to discover that when Netanyahu looks at reality from a broad historical perspective, he hardly refers to the well-known controversies that have led to so much stratification in Israeli society these days, such as the dispute over the authority of the Supreme Court, for example, or the rift between the first Israel and the second Israel. These topics are barely touched upon in the book. The real ideological conflict, according to Netanyahu, is between people who understand reality in a sober and painful way, and those who err on the side of self-deception, which prevents them from seeing the ever-present danger.

Netanyahu understands the history of Zionism in the following way: The mortal sin of the Left before World War II is that it did not foresee the impending disaster and did nothing to prevent it from happening. The mortal sin of the Left after the founding of the State of Israel is that it did not foresee the disaster of a Palestinian state and did nothing to prevent it from coming into existence.

Nevertheless, the way Netanyahu views reality makes it difficult for him to show ideological rifts within the current Israeli society. The reason for this is that from his point of view, and regarding this specific matter, the rift in the political sphere has for the most part repaired itself and dissipated.

THERE IS a consensus among most Israelis with respect to their understanding of the world we live in. Most Israelis have internalized the fact that this world is not a friendly place for Jews, and when it comes to matters of national security, we must rely solely on ourselves. Most Israelis oppose the establishment of an armed Palestinian state in Judea and Samaria. And indeed, there is unanimous support for efforts to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons. In other words, the new Israeli understanding is a practical acceptance of the narrative advocated by the Netanyahu family.

There are essential matters that are not connected to the conflict, about which Israelis do in fact disagree with one another, but these topics were barely touched upon in Netanyahu’s book. In contrast with the past, when Israelis were split into different camps over political issues, at the current time most Israelis agree with Netanyahu vis-à-vis security issues.

Benjamin Netanyahu’s victory in the battle over public consciousness is his father’s victory in the battle over ideology.

However, paradoxically, Netanyahu’s victory has turned into his biggest current problem. Now that his rivals have adopted the ideas for which he has fought, Netanyahu is having a hard time distinguishing himself from his rivals. The implicit agreement that prevails among the Israeli public regarding core political issues means that the Israeli Left no longer functions as a heavyweight ideological rival for Netanyahu.

That isn’t to say that Netanyahu doesn’t have any worthy political rivals who are talented and effective, it’s just that they are coming from the center of the political spectrum, and they hold similar stances on security issues. A clear sign of the absence of such a figure in Israel, someone who is the ideological antithesis of Netanyahu, is the place that Barack Obama occupies in the book.

Netanyahu writes the following about how he handles interactions with Obama: “I’ve never had to contend with a more difficult challenge.” Obama is described as a smart, talented figure who holds a worldview that is the polar opposite of the worldview held by Netanyahu and his father.

From Obama’s point of view, the world is a much less dangerous and hostile place, and by turning to “the better angels of our nature,” we are able to create a society that is more just and fair, without having to use force or threats. In other words, the naïveté that in the past characterized many Israelis has dissipated. As a result, when Netanyahu is searching for a figure that represents the naïveté that in the past characterized a large portion of Israeli society, he is now forced to choose someone who is not Israeli.

Benzion Netanyahu himself was privileged to see this change during his lifetime. The book includes a section of the last speech Benzion ever gave, which took place at his 100th birthday party at the Menachem Begin Heritage Center in Jerusalem. As usual, Benzion referred to the “increasing threats that could lead to the destruction of the Jewish people” and continued, as was his custom, saying that in order to overcome them, we are in need of “enormous mental power.” But then, Benzion added a statement that was very unlike anything he had ever said before. He stated that “The people of Israel are currently showing the world that they have such mental power.”

This uncharacteristic statement constitutes a dramatic pivot in Benzion Netanyahu’s understanding of reality. His life’s work was to point out that the Jewish people was not equipped with the necessary mental power to protect its existence, and yet at the end of his life, he apparently took a new look at Israeli society and saw that it had indeed acquired the mental power that would enable it to “look danger in the eye… and be prepared to enter the campaign the moment the chance of success seemed reasonable.” Benzion concluded, saying: “It is my belief, my wholehearted belief, that our people will repel the danger that threatens our existence. And with this expression of faith, I conclude my talk.”

These optimistic words came out of the mouth of a pessimistic historian. Benzion Netanyahu, the genius ideologue, came to understand at the end of his life that a great change had taken place in the Israeli consciousness – a change that was in large part due to actions taken by his son, who was his successor.

OCCASIONALLY, THE most important part of a book is precisely what has been left out. Among other things, the book describes the story of the Zionist movement and the State of Israel. In the story that Netanyahu presents here, there’s no room for Kibbutz Degania, Kibbutz Ein Harod and all the other large communities created by the Second Aliyah and the Third Aliyah. Neither is there room for the founding of Kfar Etzion, Ofra and Kedumim. The pioneers from the Labor Zionist movement and from the Gush Emunim are also missing from the story Netanyahu is telling.

None of this is accidental. According to the Netanyahu family, Zionism was a political and diplomatic achievement, not a success resulting from efforts made by pioneers who physically settled the land. For the Netanyahu family, the forefathers of Zionism are Herzl, Nordau and Jabotinsky, not Gordon, Katznelson and Rabbi Kook. According to Netanyahu, Zionism is the movement that saved the Jewish people long before it was the act of bringing about the redemption of the Land of Israel.

In one of the most honest revelations in the book, Netanyahu expresses empathy for the Uganda Plan. Netanyahu assumes that had he been living in the time of Herzl, he may not have supported this plan, but he does identify with the dilemma. The Uganda Plan was meant to save the Jewish people, and saving the Jewish people is the almost exclusive purpose of Zionism.

Netanyahu’s understanding of the Uganda Plan can be seen throughout the book in all the places where he displays careful flexibility with respect to territoriality.

As we know, throughout the years he served as prime minister, Netanyahu stated on more than one occasion that he would be willing to agree to territorial compromise on the West Bank. His followers often wonder if these proclamations were part of Netanyahu’s political cunning or if perhaps he really meant what he was saying.

If that’s the case, then, it is interesting that in his autobiography, in which Netanyahu himself serves as the official commentator of his legacy, he once again identifies with all of these proclamations. It turns out that he does not identify with the political approach that absolutely opposes the return of territories within the framework of a peace agreement. So long as the Jordan Valley remains in Israeli hands and the IDF retains freedom of movement in the entire region, Netanyahu is willing to make territorial compromises.

Netanyahu is a link in a very specific stream of Zionism: a Zionism of saving the Jewish people, as opposed to the Zionism of redeeming the land. Netanyahu’s zealousness applies only to the defense of the people of Israel, not to the holiness of the Land of Israel. Netanyahu’s hawkish stance is mainly reflected in his suspicion of the Palestinian national movement, and not in a deep emotional attachment to the Jewish settlement movement. A right-wing defined by suspicion, and not a right-wing defined by holiness.

Apparently, this is a rare combination. Usually, people express both of these sentiments together. People who are highly suspicious of the world outside of Israel’s borders also tend to attribute holiness to the Land of Israel. And people who do not consider the Land of Israel to be holy generally tend to be more naïve about the world outside of Israel.

Interestingly, neither the younger nor the elder Netanyahu considers the Land of Israel to be holy, and yet neither do they trust anyone who is not from Israel. This is a cold, sober and rational stance, both regarding human nature and the nature of the land. Humanity in its essence is not good, and neither is the land in its essence holy. And this is the premise the leader of Israel must follow.

Even though this premise is not accepted by the far Right and the far Left, it is nonetheless an expression of the widespread intuition of most Israelis that is not spoken about enough: restrained pragmatism when it comes to the Land of Israel, and unrestrained suspicion when it comes to Israel’s security.

There is a large gap between the self-portrait Netanyahu has fabricated about himself in recent years through his speeches on TV and posts on social media and the self-portrait he weaves in his book. The Netanyahu we’ve seen on social media passionately conveys feelings of persecution, deprivation and victimhood.

Conversely, in his autobiography, these feelings come across in a much more subdued manner. Although there is a chapter in the book that serves as a kind of defense of his legal entitlement and as an indictment against the system that is prosecuting him, this has all been condensed into one short chapter that is swallowed up in a very rich and long book.

In contrast to most of the appearances and public statements that Netanyahu has made in recent years, the book rarely describes his battle against Israeli governmental institutions and certain communities in Israeli society. Instead, it focuses on his struggles against Israel’s enemies and Israel’s critics.

Netanyahu’s decision to shrink the amount of space he allotted in his book to his personal legal battle and instead allocate a generous part of the book to his ideology was an important choice made by a person with a highly developed historical awareness, who is leaving Israeli society with an important document that presents the self-awareness of one of Israel’s most influential political leaders.

All roads lead to the paradox that is Netanyahu. No other individual in Israeli politics is as controversial as Netanyahu. His supporters adore him, and his detractors loathe him. His supporters tend to hate everyone who does not support him; his detractors, who are the mirror image of his supporters, tend to hate everyone who supports him.

Therein lies the tragic gap between Netanyahu’s image and Netanyahu’s ideology. At the beginning of the third decade of the 21st century, Netanyahu’s character is the basis of a hurtful and paralyzing controversy, while Netanyahu’s ideology is the basis for broad and hidden agreement.

Translated by Hannah Hochner.

The article was first published in Makor Rishon and is republished with the paper’s permission.