In recent months, almost a decade since her husband’s death, the nocturnal dreams of Jenny Oscar have become more vivid. “We are in the car,” she describes, and her eyes open. “Hillel, my late husband, is in the driver’s seat, and I’m sitting next to him. I look at him from the side, and his beauty is breathtaking. It’s afternoon. We’re driving on an empty road in the south of Israel, and the sky is painted a reddish blue. Our car is the only one driving on the straight road that never ends. We don’t talk at all, but I remember feeling peaceful and calm. Then, in one moment, Hillel suddenly moves his right hand from the steering wheel and turns up the volume of the music playing on the radio. I think it was a French chanson. Something by Edith Piaf, if I’m not mistaken.”

Hillel’s widow says that at that point, she turns her head to the right, notices a stop sign, and suddenly hears the screeching of brakes. “That’s when I wake up.”

Jenny has been devoting the last period of time to in-depth consultations with several fortune tellers (\among them Turkish coffee cup readers; tarot card wizards; and experts in deciphering encrypted secrets by reading a crystal ball) who are trying to interpret the dream for her and find out if there is a message hidden there.

“In the first years after his death, I wasn’t able to dream about him at all,” she sighs. “Suddenly he comes to me every night. I just can’t understand why now? What is he trying to tell me? I know Hillel. It’s completely clear that he’s trying to convey a message to me in this dream, don’t you think?”

Jenny doesn’t really wait for an answer. We are sitting in her apartment in Ashdod (about 50 km. south of Tel Aviv), where she is currently nannying for her three-year-old grandson, who keeps running around the house holding a racket and kicking a ball. “’Hillel, come to the table, honey. Your lunch is ready.’ He’s just like his grandfather. He’s always chasing a ball,” she says.

A distance of over 14,000 kilometers separates the city of Ashdod in Israel and Macksville. New South Wales, Australia. These two geographical ends also embody mental and cultural gaps.

From Israel to Australia: A tragic coincidence

While Jenny is constantly trying to lull her restless grandson to a nap in their cramped Middle Eastern home, father and daughter Greg and Megan Hughes are sitting in the stands at the Sydney Royal Calf Show looking for the best genetics to breed the herd that the family has nurtured for many years. Until about a decade ago, Greg had another partner on the calf trading trips. “I used to come to Sydney with my son Phillip,” he recalls. “These were very special moments for us. We waited for this for a whole year. A few quality days with my son. Just him and me.” Through these trips, Greg says he was able to remark his son’s soaring popularity. “Every year, I saw more and more people rallying around him. I always knew that my son was talented in cricket, but I could never understand how much he was loved.”

Since Phillip’s death about a decade ago, his sister, Megan, occupies the seat next to the driver. In recent years, she has been attending the Faculty of Business at the University of Sydney. During her vacations from school, she goes on trips across the continent with her father to expand and improve the family herd of calves. “Cricket was Phillip’s passion, but cattle and farming are his legacy,” she says.

The last week of November 2014 will be remembered as one of the deadliest weeks in the history of cricket. On November 25, 2014, Phillip Hughes was hit in the neck by a bouncer during a Sheffield Shield match at the Sydney Cricket Ground, causing a vertebral artery dissection that led to a subarachnoid hemorrhage. The Australian team doctor, Peter Brukner, noted that only 100 such cases had ever been reported, with “only one case reported as a result of a cricket ball.” Hughes was taken to St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney, where he underwent surgery, was placed into an induced coma and was in intensive care in critical condition. He never regained consciousness and died on November 27, three days before his 26th birthday.

Two days later, on a sunny Saturday in Israel, former national captain Hillel Oscar left his home in Ashdod for a game in the local cricket league, where he was to serve as umpire. Oscar was not wearing a protective helmet, since the likelihood of injury is regarded as extremely low. “Just before he went out to the cricket match, like every Saturday, Hillel told me he was going to have a minute of silence in memory of a cricketer who was killed in Australia. He said he would take a picture of it and send it to me so I could upload it to the Twitter and Facebook accounts of the Israeli Cricket Association. Instead, I received the sad news of Hillel’s fatal injury,” says Jenny. One of the players told her that the incident happened when a batsman struck a ball with tremendous power, and it rebounded off the stumps and hit Oscar. “The ball flew in the direction of the umpire with great force, struck the wicket, and hit him in the face,” the player said.

Oscar had a heart attack after the injury. A team of medics performed CPR on him and took him in critical condition to Barzilai Hospital in Ashkelon, where he was pronounced dead a few hours later. The message from the hospital’s spokeswoman, Ayelet Kidar, was succinct: “A cricket umpire arrived at the medical center who was seriously injured by being hit by the game ball. After CPR on the field and in the hospital, unfortunately, he was pronounced dead.”

It is quite complex to try to compare the two. Phillip Hughes’s future was still ahead of him, while Hillel Oscar was due to celebrate his 59th birthday shortly after the incident. The game’s popularity in Australia is also immeasurably greater than that in Israel, but it seems that in order to put together the incredible timelessness and chilling similarity between the two cases, it is necessary to go all the way to India. A few hours after Hughes’s funeral, the President of India, Narendra Modi, tweeted on his Twitter account: “Heart-rending funeral in Australia. Phil Hughes, we will miss you. Your game & exuberance won you fans all over! RIP.”

A few days later, Moran Asraf, Hillel’s bereaved daughter, saw on her cellphone screen the international area code of India. “During the shiva [the week-long mourning period in Judaism for first-degree relatives], we received condolence calls from old childhood friends of Dad who grew up with him in Mumbai. I was convinced that it was a similar call.” But, to her astonishment, at the other end of the line was the representative of the Israeli embassy in New Delhi. He wanted to link her to the president of the giant country. “I was shocked for a few seconds and didn’t know what to do,” she recalls. “Without thinking, I passed the phone to Nouriel, my uncle. It was a strange moment. In Israel, no official from the state called to console, and suddenly the president of India wants to talk to us?”

“It was a short conversation, but I felt President Modi’s sincere participation in our grief,” says Nouriel, the bereaved brother. “Over 40 years have passed since our family immigrated to Israel from India. We are very happy here, even though Israel has not always given us the feeling that we, the immigrants, really belong to the country. Speaking Hindi after so many years was an extraordinary moment that managed to bring me back decades, to my childhood years in India,” he recounts.

The manner of integration of the Indians in Israel can be somewhat reminiscent of the difficult reception of cricket in the country. Long before the State of Israel was founded, the possibility of cricket in a Jewish state was visualized by Theodor Herzl. In his book Altneuland (“The Old New Land”), he painted a picture of Jews playing cricket on the green fields of the Promised Land.

The Ottoman Empire was not a cricketing country. In 1902, the Jewish state was a dream, and cricket there was a dream within a dream. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Balfour Declaration in 1917, and the subsequent British Mandate brought both dreams a little closer to realization. The earliest cricketing story in Mandatory Palestine that comes to mind is of a match in the 1920s, when Prof. Norman Bentwich, the British Mandate’s Jewish attorney-general, was fearful of losing his place in the cabinet after dropping a catch in front of Sir Herbert (later Lord) Samuel, the high commissioner.

Israel was founded in 1948 and during its first years, the cricket played was very sporadic in nature, and little is documented of its existence. However, since the 1960s, Jewish immigrants from Commonwealth countries have played a vital role in the sport’s resurgence. Indian Jews belonging to the Bene Israel community founded the country’s first cricket club, in the southern city of Beersheba. The national league, consisting of 10 clubs, was also set up during this time. Estimated to number 80,000 today, the Bene Israeli community maintain their Indian roots through their shared love of Indian food, Bollywood movies and, of course, cricket.

“Hillel’s whole life was around cricket,” continues his brother. “I’m a year older than him, and from a young age we were inseparable, even though we were very different in character: Hillel was a lifer, and I was more conservative and obedient. When we went to school together, my mother ordered me to hold his hand and make sure he entered the classroom. However, this almost never happened .While walking, he would let go of my hand, run to the nearby cricket ground and just watch the games. At one point, the players on the field invited him to join. When one of the teachers came to visit our home, our parents asked him about Hillel’s academic performance. The poor teacher didn’t even know he had such a student.”

In the mid-1970s, when Hillel was 15 years old, the family immigrated to Israel. “We had a very good life in Mumbai,” continues Nouriel. “The only reason the family chose to leave India was because we didn’t go to a Jewish school and were very far from the Jewish community. Our parents were very worried that we would meet non-Jewish girls and marry them. They could not accept such a fate. Within a year, Father liquidated his business, sold the house, and we moved to Israel.”

Unlike the brothers who flourished in the new country, the acclimatization of the parents in Israel was complex. “From the moment we landed in Israel, at the airport they re-spelled our last name. In a few minutes, we turned from the Awasker family to the Oscar family. ‘It just sounds better in Hebrew,’ the official at the border control told my parents.”

Nouriel also says that the family’s standard of living dropped greatly. The family was sent to remote settlements in southern Israel near the border with Egypt. The father of the family had to support his children through odd jobs. “Two years after we moved to Israel, Hillel and I enlisted in the army and integrated into Israeli life. For the parents, it was more difficult. They were quite lost in the new country. Although Jews, they did not really belong. It was not easy to see this.”

For the pair of brothers, on the other hand, the only problem was the Israeli cricket culture. More correctly, the almost complete absence of the game in the world of Israeli sports.

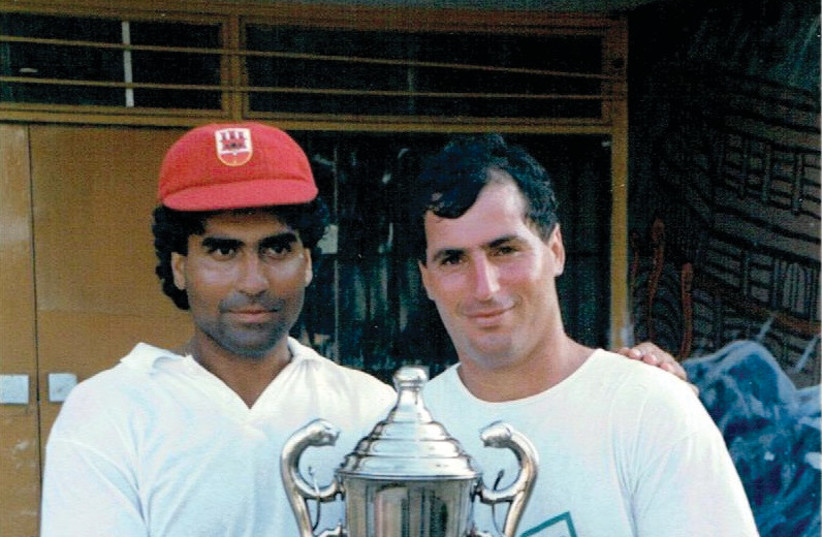

“In those years, the cricket fans in Israel numbered a few dozen,” recalls Felix Avitan, who would later become Hillel’s close friend on the Israeli national team. “We were constantly looking for players. One day a rumor spread that there was a cricketer who had come to Israel from India. I will never forget the first time I saw him bat. He was clearly the best batsman who had ever played in Israel. A few years later, we founded a cricket team together, Ashdod A, and Hillel played for it\ until the day he died. He contributed a lot to the team’s success and marched it to achievements, wins and state championships. He knew how to respect every player, and everyone loved him. I miss him to this day.”

Over nine years have passed since the death of their son, and the Hughes family continues to grieve. Over the years, the family has waged a persistent legal battle against the Australian Cricket Association, after which they decided to abstain almost entirely from media appearances.

“Phillip’s death, as tragedies of this type tend to do, wounded all four of us in different ways,” says Jason Hughes, whose eulogy for his brother has garnered nearly 10 million views on YouTube. “I can tell you that I miss my brother very much. He is really missed on a daily level. I have so many things to tell him. I still can’t dream about him.”

When asked “Did you know the story about the Israeli referee Hillel Oscar, who was killed on the cricket field 48 hours after your brother’s case?” he replies as follows:

“I think I’ve heard something about it before, but I didn’t pay that much attention to it. I was busy gathering my family and trying to get through that horrible time together. Anyway, it’s terrible. Obviously. You are welcome to give them my condolences. Maybe, sometime in the future, we will also be able to establish some kind of contact. I am not a person who deals with mysticism, but there is no doubt that there is a chilling similarity between the two cases. Death on a cricket field (sigh). Go figure!” ■