The story of Henrietta Szold, a heroine to humanism, Zionism and equality, is in many ways the story of modern Jewish history leading up to and in the wake of the First and Second world wars. The experiences that incited her to act and the pivotal work she did influenced the Jewish world tremendously.

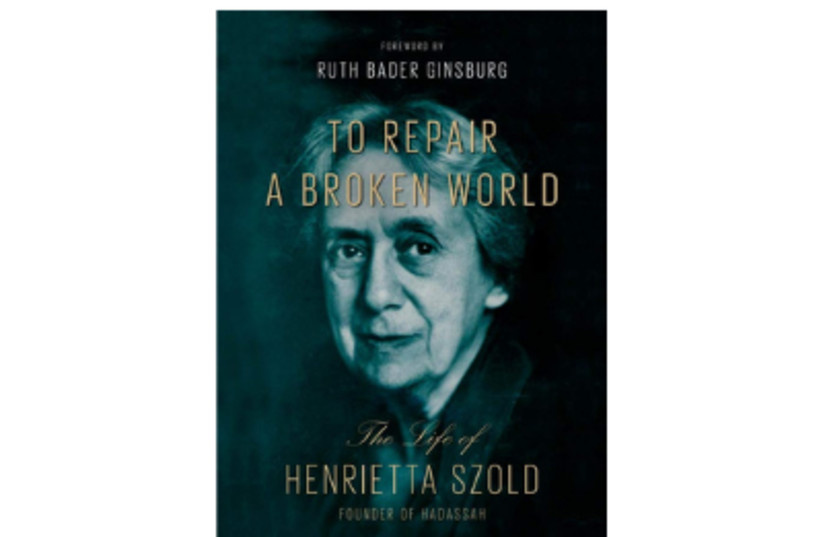

To Repair a Broken World, Modern Jewish History Professor Dvora Hacohen’s salute to Szold’s life, reveals the enormity of Szold’s achievements in a period when prejudice toward women and Jews put her at quite the disadvantage.

Szold’s childhood in Baltimore was marked with the Civil War, news of antisemitic pogroms in Eastern Europe, and disputes between American Jewry’s Reform and Conservative movements. Szold followed her father’s footsteps in supporting the abolition of slavery and equality for all. She was outspoken, writing from a young age about the injustice of the Trefa Banquet, an attempt to bring all Jewish congregations in the US together under the Reform movement, where Orthodox attendees were served a meal including seafood, frog, pigeon, and other non-kosher delicacies.

Szold also criticized the cruel treatment of Eastern European Jewish refugees by American Jewry. But speaking up against these issues was not enough for Szold.

Despite never having attended college, the self-taught Szold was bright, creative, practical and single-mindedly determined. Seeing the plight of uneducated and impoverished immigrants in her city, Szold established by herself a night school to teach English, providing all those wishing to attend with the tools to find work and assimilate into American culture. Other cities across America soon followed suit and modeled their night schools after Szold’s.

Her success was not publicly acknowledged until many years later, when she was awarded the key to New York City and an honorary doctorate from Boston University. In fact, most of her early work, including extensive editing, translation and proofreading for the Jewish Publication Society, went uncredited because she was a woman. She also felt that the man she had fallen in love with at the time had used her solely for her gifted writing and editing skills, causing her to feel shattered and useless.

Certain that Jews required a safe haven from the antisemitism spreading quickly across Europe and even in America, Szold was then at the forefront of American Zionism, just as the Zionist Congress in Europe first convened. After visiting Palestine under Ottoman rule, Szold realized that the country was in no condition to absorb Jewish immigrants. While there she witnessed destitution, disease and a frightening sight of “clouds of flies swarmed around... children’s faces and eyes.”

Though she felt crushed by heartbreak and sorrow in her personal life, Szold was stirred by the dire circumstances of her fellow Jews across the world. Inspired by women such as the Jewish poetess Emma Lazarus, who wrote the “The New Colossus” inscribed on the Statue of Liberty requesting that America allow refugees to pass through its borders, and American nurse Lilian Wald, who had established the Henry Street Settlement in New York City for community social work and healthcare, Szold formulated a grand idea: she would establish an organization to encompass all the obstacles and predicaments she had thus far encountered.

Szold formed the American women’s Zionist organization Hadassah, which became an “anchor for Szold’s efforts for the empowerment of women and for the struggle for their equal rights” both in America and Palestine, where “poverty and disease had a disproportionate effect on women who were forced day in and day out to care for children,” Hacohen writes. Hadassah’s first project was to establish a neighborhood clinic in Jerusalem, modeled after the Henry Street Settlement and Jane Adams’ Hull House, which offered medical care and supplies, health education, and support for mothers. The clinic soon branched out to other major cities. Hadassah’s medical clinics arrived just in time, as starvation and disease had engulfed Jewish communities in the country by the outbreak of World War I.

Toward the onset of World War II, Szold was again charged with a vast responsibility. She oversaw the Youth Aliyah movement that rescued well over 30,000 children from the grips of Nazi Germany, bringing them to Palestine and placing them in kibbutzim and other communities. Youth Aliyah member Shimon Sachs said of Szold: “She gave voice to the anguish in our hearts and to our fears in the Diaspora.”

Szold buried herself in the work she so believed in, sacrificing her personal life and health to support others. She never married nor had her own children, yet she mothered the lonely and terrified children survivors of the Holocaust and looked after the welfare of her fellow Jews living in Palestine and the Diaspora.

Hacohen’s retelling of Szold’s life sheds light on the magnitude of Szold’s courage and determination in an extremely rich and well-researched account. She elegantly pieces together historical documents and personal letters collected across continents to create a revealing and inspirational narrative.

To Repair a Broken World is a must-have on the bookshelf of every Jew who values the history and individuals who fought for his survival. It is a tribute to a period of Jewish history not addressed often enough, and not just to Szold but to the many Jewish figures of that time who paved the way to a Jewish homeland, and sought endlessly to repair a broken world in one of its darkest hours.

To Repair a Broken World

By Dvora Hacohen

Harvard University Press

400 pages; $35