In 1924, the first Islamic books arrived at the nascent National Library of Israel, then part of the newly created Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The Zionist executive purchased from Ignac Goldziher – a Hungarian Jew who was one of the most important scholars of Islam in the 20th century – a research library of 6,000 volumes that formed the basis for the library’s Arabic and Islamic Studies Collection.

Today, for the third year since the corona pandemic began – and with the National Library’s project to digitally scan its entire collection almost complete – the library has launched its Hebrew and Arabic “Ramadan Online” project in honor of Ramadan, which among other online programming includes the showing of pages from three of the rare manuscripts from the collection.

The NLI’s Islam and Middle East Collection is one of the region’s leading collections of its kind, featuring over 150,000 Arabic volumes, and thousands of manuscripts and rare books dating from the ninth to the 20th centuries. It encompasses 2,500 Islamic manuscripts in Arabic, Persian and Turkish, including some manuscripts that were included in the Goldziher collection.

The major part of the manuscript collection, however, was donated by Abraham Shalom Yahuda, a Jewish Jerusalemite born into a Baghdadi-Ashkenazi family in 1877. Fluent in Arabic, he was a leading scholar of Jewish and Islamic studies, and one of the most important collectors and traders of Arabic manuscripts in the 20th century.

“He had a good eye for quality, and found, purchased and sold internationally incredible manuscripts,” said Dr. Samuel Thrope, curator of the NIL’s Islam and Middle East Collection.

The Islamic manuscripts in the Yahuda Collection include examples of all major fields that make up Islamic scholarship, Thrope said. These include rare and beautiful copies of the Koran, copies of the hadith – which records the traditions and sayings of the Prophet Muhammad – Islamic law, philosophy, literature and a number of mystic Sufi texts.

The manuscripts span from the ninth century, a mere 200 years after the Islamic conquests of the Middle East, to the 19th century. Despite printing having already begun in the Arabic world and Ottoman Empire, people were still writing manuscripts even at that late date, said Thrope.

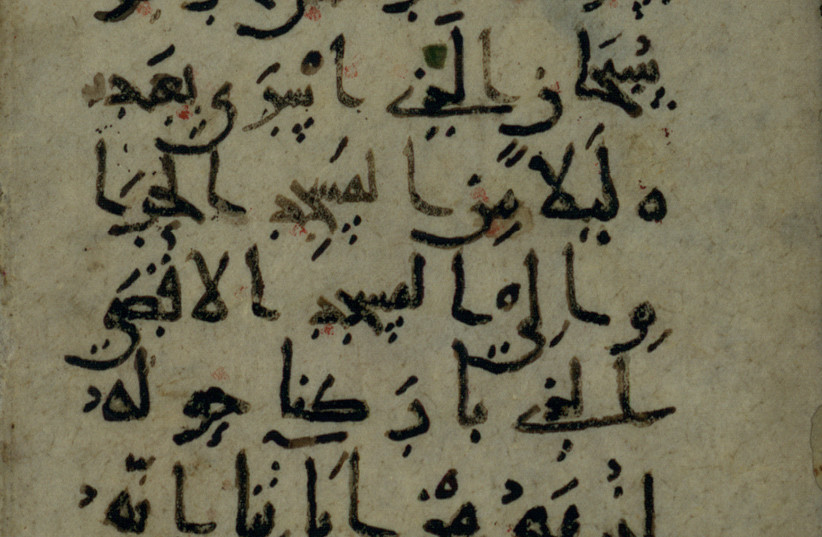

The three manuscript pages presented with digital annotations in Ramadan Online include an early ninth-century Koran from Iran. This early Koran contains a colophon, or publisher’s imprint, at the end, with information about the scribe written in Persian using an Arabic script called kufic. It contains golden written embellishments of the names of the Koran’s chapters in the shape of a palm tree.

Also in the holiday project is a page from a 16th-century Koran that includes chapter 2, verse 185, which refers to Ramadan. It is beautifully written on paper partly in gold and partly in blue ink made from lapis lazuli, representing the transition from parchment to paper that happened earlier in the eighth century.

This unique Koran from the Yahuda Collection was written in Iran under the Safavid Empire, noted Thrope, which turned Iran into a majority Shi’ite region, while most of the Islamic world follows the Sunni tradition.

Among the differences of the two traditions is the Shi’ite belief in the inherent holiness of Muhammad’s family to the 12th and last imam, including his cousin and son-in-law Ali, who is mentioned in the Shi’ite version of the Declaration of Faith. This declaration was written in gold with a great deal of prominence on the final page of this Koran.

The manuscript later became part of the Ottoman royal library, patrons of Sunni Islam, and this portion of the declaration was covered in gold leaf.

“This is a lesson of how manuscripts are mobile works of art that can be created by one individual or group and then redirected and repurposed,” said Thrope, noting that as manuscripts were bought and sold, different owners inscribed their own names on it leaving an historical trail.

“In this way, we can understand the intellectual history of the manuscript, who read it, and where and how it was moving,” he said. “A manuscript is much more than a book. Studying a manuscript is like doing an archaeological dig. You unearth different layers of text as history, as material, as art, as provenance.”

The third page that forms the holiday online manuscript display is from a 15th-century copy of Sahih al-Bukhari, one of the six major collections of Sunni hadith based on the teachings, sayings, traditions and practices of Muhammad.

“The science of hadith studies the authenticity and transmitters of the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, in many ways like Talmudic discussions of earlier rabbinic statements,” explained Thorpe.

Though not a part of Ramadan Online, Thorpe said a manuscript from the collection that stands out for him is a 19th-century manuscript from the Goldziher library copied in Egypt, apparently specifically for him at his behest. The manuscript includes his own handwritten notes, reflections and corrections in Arabic and German in the margins.

“It is amazing to have this,” said Thrope. “What makes it most important for me is that it is a testament to the continuation of Islamic intellectual traditions and how it crosses borders.

“Goldziher was a Hungarian Jew who was an expert in and admirer of Islam. It speaks a lot of what we are trying to do in the library: enabling this kind of scholarship that allows people from different backgrounds and different stories, different passions, to take part in this civilization.”