BUENOS AIRES — Argentina set a new national record for the number of athletes it sent to the Maccabiah Games in Israel this year — 657 players, in a total delegation of 786, including coaches and other staff.

But there were far more Argentine athletes in total at the games. They were just wearing different countries’ uniforms.

Take for example the Netherlands’ female hockey team, which had a couple of Argentine players on its roster, or the under-16 Paraguayan soccer team, which used 15 Argentines to create a team large enough to qualify for competition.

Then there were the entire Uruguayan under-35 and under-45 teams — made up entirely of Argentines.

The phenomenon was the product of the Games’ rules, which in some cases allows players with residencies in multiple countries the opportunity to play for any of those nations — and which organizers have been flexible about — in combination with the sheer amount of Argentines who play in competitive amateur Jewish sports leagues, especially soccer ones, back home.

"The Jewish Olympics"

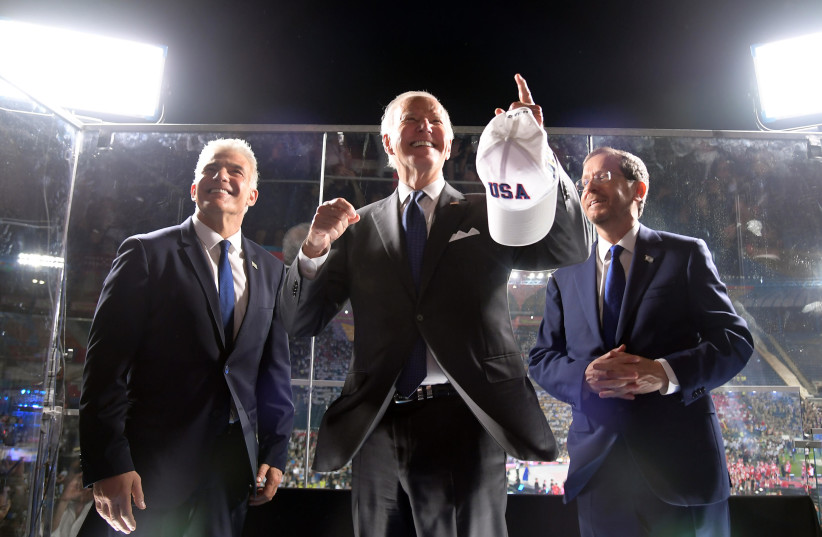

The Maccabiah Games, often nicknamed the Jewish Olympics, takes place every four years in Israel, bringing together many of the best amateur Jewish athletes from dozens of countries. The 2022 tournament, which ended on Tuesday, received a headline news boost when President Joe Biden attended the opening ceremony earlier this month. Around 10,000 athletes participated this year.

The competition is eagerly anticipated in Argentina, a country with arguably the world’s highest-quality levels of amateur Jewish sports leagues. Each weekend, thousands of athletes sweat their t-shirts throughout the country at Jewish community clubs that have strong ties to Israel.

The case is particularly true for soccer: The Jewish soccer league under the umbrella of FACCMA — the local Federation of Maccabean Institutions — is the second largest of its kind nationwide, only surpassed by the country’s top pro league, the Argentine Football Association. FACCMA is the largest member of the Latin American branch of the Maccabi World Union, with 55 affiliates and a network of more than 50,000 members.

The Argentine phenomenon began even before the start of the Games. The under-18 soccer teams for Argentina and Uruguay squared off in an exhibition match in Haifa on July 13 — except all 22 players on the field were from Argentina, friends from Jewish leagues back home. To give an idea of the interest: over 180 players had applied for only 22 spots on Argentina’s U-18 squad.

The under-55 Uruguayan soccer team was a mix of 15 Argentinians and 9 Uruguayans, directed by an Uruguayan coach. They had met four times to get to know each other, including once at a training camp in Punta del Este, a coastal Uruguayan city frequented by many Argentine Jews in the summer.

Argentine Adrian Krochik praised the Games’ flexibility, which allowed him to participate as a member of the under-55 Uruguayan team. But there was one thing he missed, as a member of Uruguay’s official delegation: “the opening ceremony, under the Argentine flag,” he told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

The Argentines who play for other countries represent “a small number among the 10,000 athletes who participate in the Maccabiah, but they provide real support to the smaller delegations,” said Rabbi Carlos Tapiero, vice director of the Maccabi World Union, which runs the Games.

For Paraguay’s delegation, it was the first time in 20 years that the country was able to send a team to participate in group play, as opposed to individual competitors, according to Mariano Mirelman, head of the World Jewish Congress’ Paraguay communal organization. The WJC estimates that there are around 1,000 Jews in Paraguay — compared to the hundreds of thousands who live in Argentina.

Guido Becher, an Argentine currently living in Colombia, wanted to form an over-45 Colombian soccer team with his friends but didn’t have enough local players to do so. He called a friend from Cleveland, two in Los Angeles, one in Switzerland — and 11 in Argentina.

Even though the final roster only had six Colombian players and a Colombian coach, the team contributed to what became Colombia’s largest-ever delegation to the Games.

“It’s emotional for me to see that even with the economic problems in my native country, all my friends made a great effort to reach the event,” Becher said.