Financial journalist Daniel Gross is of proud Syrian-Jewish stock on his mother’s side. Yet the historian and author of nine books knew about the very private billionaire Edmond J. Safra in only the vaguest terms.

“I knew him as a rich guy and a banker who lived in different places,” Gross laughs. “I thought I had some privileged insight because firstly, I’ve been a financial journalist for 30 years, and I’ve interviewed a lot of the major figures in global finance at a very high level. Secondly, Safra is the biggest name in the Syrian Jewish community.”

Gross, the author of the newly released A Banker’s Journey: How Edmond Safra Built a Global Financial Empire, spoke to the Magazine to get to the heart of the man who made monumental contributions to the State of Israel, while never actually claiming citizenship or owning a home here.

<br>The timing was right

Edmond J. Safra has been dead for nearly 23 years. When Gross received the request of the Edmond J. Safra Foundation to write this biography, it came with the express cooperation of Safra’s widow, Lily, who sadly passed away just weeks before the release of this book.

Gross was granted access to a trove of private archives and more than 300 interviews that traced the story of Safra’s life, from his childhood in Beirut as the son of Banque de Crédit National owner Jacob Safra, to his shocking demise in a fire at his home in Monaco in 1999.

“Edmond had been sent by his father to Milan at age 15 to literally run around the central banks of Europe buying gold. When he was 20, and the family needed to get out of Beirut, it was Edmond who decided the family were going to Brazil,” he says. “He couldn’t get citizenship in Europe. America wouldn’t take people. His father was already in his sixties, and Edmond was effectively a surrogate father for his two younger brothers. He paid the tuition of his brother Joseph at boarding school in England. There’s a great letter he wrote to the dean of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania in 1957: ‘Can Joseph come for just two years and take banking courses?’ Edmond had this sense of self-possession. He had already been doing business by the time he was 22 with the Rothschilds, but Wharton didn’t know him from anybody. The answer was no.”

Family and personal papers in seven languages formed the backbone of this biography. Besides offering a deep dive into the international banking climate of the second half of the 20th century, Gross shows how Safra was perceived by the international banking community in extremes. He was a financial prodigy whose ethics reached deep into the Torah; and as a feared competitor globally, he could be reviled for his old-fashioned way of keeping his banks close to his sleeve, installing family and members of the displaced Syrian and Beirut Jewish communities in banks that operated from Brazil, the US, Europe and, eventually, the Far East and Israel.

“Part of what makes it very compelling to me is that to be a Jew in the 20th century was to be displaced. We know an awful lot about Europe, Eastern and Western Europe. We know some about the Sephardi experience – Morocco, Yemen, Iran, Iraq, etc. – and comparatively little about Syria, and especially the Lebanese, which is a very unique community. The Beirut Jewish community was about 6,000 people at its peak before the founding of the State of Israel, so it was pretty small. The Great Aleppo Synagogue in Syria has a cornerstone from 300 CE, which is one of the longest continuous Jewish communities in the world. Beirut didn’t form their big synagogue until 1927. So even though it was only 150 miles away as part of the Ottoman Empire, that community only formed and crystallized in the late 19th century, early 20th century,” he says.

Gross notes that many Jews who landed in Beirut, like the Safras, had come from Aleppo and Damascus. “In 1947-1948, you had pogroms in Aleppo and you had pogroms in Baghdad. The Israelis went and brought everyone out of Morocco. In 1948 they brought everyone out of Yemen. Beirut had this sense of coexistence, where the Jews were not only sort of protected but part of the establishment. Through the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, there was a functioning Jewish community in Beirut, and Edmond was going to Beirut till the time of the civil war. That’s a very different kind of experience than much of the rest of the experience of Jews in the Arab world,” Gross says, adding that Safra was someone who had multiple identities.

“He was a banker and a philanthropist. He was an heir to a multi-generational banking family, and also an entrepreneur who did start-ups. He maintained his Lebanese citizenship and passport throughout his entire life, after the civil war and after the Israeli invasions. He still owned his father Jacob’s Banque de Crédit National, BCN, the bank that his father founded in 1920 and continued to operate until his death in 1999. He had other banks in the world worth billions. Yet he clung fiercely to this little bank and to his citizenship.”

“He was a banker and a philanthropist. He was an heir to a multi-generational banking family, and also an entrepreneur who did start-ups. He maintained his Lebanese citizenship and passport throughout his entire life, after the civil war and after the Israeli invasions. He still owned his father Jacob’s Banque de Crédit National, BCN, the bank that his father founded in 1920 and continued to operate until his death in 1999. He had other banks in the world worth billions. Yet he clung fiercely to this little bank and to his citizenship.”

Daniel Gross

In both Aleppo and Beirut, the Jewish communities had formal councils to make sure people were taken care of, and the Safra family, being what Gross describes as almost the aristocrats of this community, were the leaders among the leaders of the formal organization. Jacob Safra, Edmond’s father, had been the president of the Beirut Jewish community.

“From a very young age, the mantle of leadership, of sponsorship, of both Beirut and Aleppo communities fell on Edmond’s shoulders. It was his personal wealth and his banks which were the vehicles for protecting people’s savings, for helping them get started in exile.”

The letters Gross discovered among Safra’s personal documents went like this: “I’m fleeing Beirut, I need a job,” and Edmond would respond: “Come to Brazil. I have a job for you.” In São Paulo, the Safra brothers had set up Banco Safra. Another letter read: “We’ve got to get out of Beirut. We’re going to New York.”

By the 1960s, Edmond had founded Republic Bank and was in the process of turning this small bank into the 14th-largest in the United States. “Come to New York. I have a job for you,” Edmond would write back.”

Safra’s loyalty to the Beirut and Syrian Jewish communities came at a steep price, though.

“Edmond was doing business in the ’40s and ’50s with Saudis and Kuwaitis,” Gross says. “He had networks with Sephardi Jews all over the world and into the Arab world generally. He felt that he had to keep a low profile regarding his identification with Israel because if he didn’t, then the Jews in Beirut and Syria would suffer. They were effectively hostages in some way, and he was looking after them.”

Philanthropy in Israel

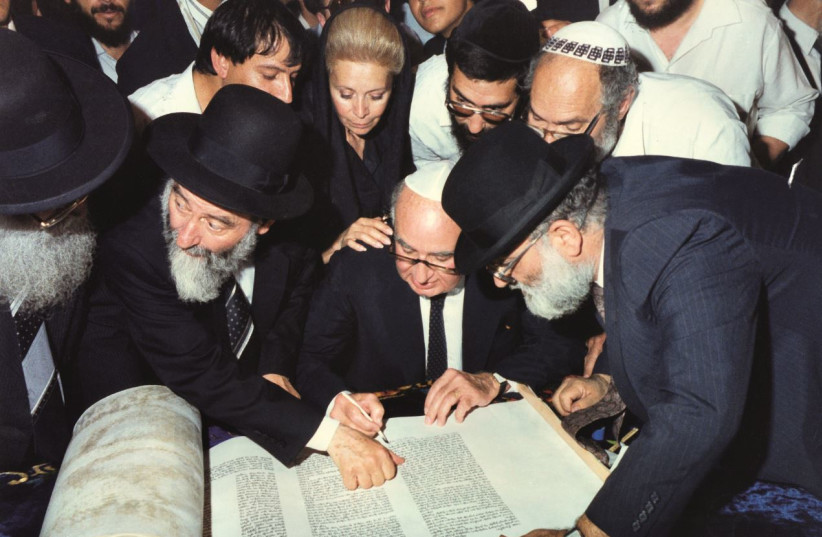

Gross discovered that the Safra family had been among the biggest supporters of Porat Yosef, the yeshiva in Jerusalem’s Old City created by Aleppo Jews, dating back to the 1940s and ’50s.

Safra, like his father Jacob before him, had a particular reverence for Rabbi Meir Baal Haness, a Roman-era Tannaitic scholar, whose grave in Tiberias became a shrine for both Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews. Edmond sent money to Tiberias to renovate the Baal Haness ruins in his father’s name in the 1950s.

In 1977, Beirut Rabbi Yaakov Atiya made aliyah, settled in Bat Yam and over the next four years, Safra single-handedly built the synagogue, leading to his first true visit to Israel since a stopover at Lod Airport in 1947. A few years earlier, in 1975, he had created the Fondation Terris, pledging $1 million to support the construction and maintenance of Sephardi synagogues and religious institutions in Israel. The work would be overseen by a committee that included Chief Rabbi Ovadia Yosef and two government representatives.

“Barely 6% of Sephardic Jews in Israel attended college, and many were pushed into vocational schools. Edmond’s goal was to give Sephardic children a better chance of integrating fully into Israeli society through opportunities for higher levels of education by establishing, in 1977, the International Sephardic Education Foundation, ISEF.”

Daniel Gross

“Barely 6% of Sephardic Jews in Israel attended college, and many were pushed into vocational schools,” Gross writes in A Banker’s Journey. “Edmond’s goal was to give Sephardic children a better chance of integrating fully into Israeli society through opportunities for higher levels of education by establishing, in 1977, the International Sephardic Education Foundation, ISEF.

“There are many records of him supporting charities in Israel, but he was always a little cagey about public identification with Israel’s political leaders. He would meet privately with Moshe Dayan. He was involved in emergency fundraising in the wake of the Yom Kippur War but was keeping it quiet publicly because he feared what would happen not only to his businesses but also to the Jewish community in Beirut and Aleppo, with whom he was identified, if he was too public,” Gross says.

In the 1980s and ’90s, with most of the remaining Jewish population out of Lebanon and Syria, Safra started coming to Israel more frequently, and his philanthropy came to light with the naming of Jerusalem’s municipal campus Safra Square in honor of his parents. At auction, he purchased the manuscript of Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity to give to the Israel Museum. In 1991, the Safra brothers expanded their banking activities in Israel with the purchase of FIBI, the First International Bank of Israel.

<br>Vendetta and vindication

Gross notes that there was always this question about how the Safras made their money. “His companies were publicly held, and you could be a shareholder. It wasn’t a secret as to how they were making money. But his view of banking was at odds with, say, what CitiGroup or JP Morgan did. His view was that his first responsibility was to his depositors. In the US, we have deposit insurance. In Lebanon, there was no deposit insurance. Your deposit insurance was your name. You borrowed on your family’s name, and if you didn’t pay back, that was a mark of shame.

“His view of banking was that first, ‘I’m going to protect my depositors, and as a result I’m not going to lend to people I don’t know. I’m not going to make credit cards so that anyone could borrow money from me. I’m not going to make mortgages.’ He would lend to very large established companies, and he would lend to governments because governments generally paid back their debts. And he would lend to the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. From his perspective, he would rather make a loan at 4% that was guaranteed by the World Bank than at 8% to somebody else and have to worry about being paid back,” Gross says, adding: “Edmond didn’t respect organizational charts. He would call a bank manager or a lower-level loan officer if he wanted information – and many junior people enjoyed a direct connection to the boss.”

The only book to be written about Edmond Safra until now has been Vendetta: American Express and the Smearing of Edmond Safra, a work that looked into a secret operation involving American Express and its hired spies, double agents and journalists-turned-henchmen bent on a mission to harm Safra. Author Bryan Burrough penned nearly 500 pages to vindicate Safra, leaving Gross a broader agenda to focus on less sensationalism and more on the enormity of Safra’s banking and philanthropic legacy.

Safra had married Brazilian-born socialite Lily Watkins, whose mother was Ukrainian-Jewish and father was a Scottish-Jewish engineer. They married in their forties and never had children together, although family photographs show Safra relaxed and clearly reveling in his role as a family man to Lily’s surviving children and grandchildren from a previous marriage. The Safras never quite recovered from the tragic news of the death of Lily’s son Claudio and their grandson in a car accident in Brazil in 1989.

Lily Safra passed away this summer at age 87 from pancreatic cancer. Chairwoman of the Edmond J. Safra Foundation, which supported hundreds of organizations around the world, an A-list guest and entertainer to Europe’s highest royals, her death in Geneva marked the end of an era.

“Edmond didn’t play golf, tennis or have many leisure pursuits, but collecting was a passion he shared with Lily,” Gross writes. “He loved the chase of bidding, calculating relative value, and understanding the dynamics of auctions in the same way he loved delving into markets and hunting for deals, whether it was paintings, drawing, sculptures, carpets, furniture, decorative objects or watches.”

It’s fun to speculate what Safra’s reprise would have been to this impressive overview of his life both inside and beyond banking. Daniel Gross discovered that “Edmond would often respond in Hebrew with the first line of Ecclesiastes, Kohelet, saying that everything is vanity, everything man does ultimately is futile, for the world continues to turn and the sun rises and sets as before, and man cannot alter things in any meaningful way.”

And yet, here it is, in Israel and far beyond: proof that Edmond Safra may have proven Ecclesiastes wrong. His family legacy is alive and well, primed to continue for only heaven knows how many more sunrises and sunsets.

A Banker’s Journey: How Edmond J. Safra Built a Global Empire, by Daniel Gross, is available in hardcover and Kindle editions.

The writer is an artist and the author of The Wagamama Bride: A Jewish Family Saga Made in Japan.