It is not uncommon for ambassadors presenting their credentials to President Isaac Herzog to do so in Hebrew, having painfully learned the short, transliterated text, and practiced either with someone in their office or with Gil Haskel, chief of protocol at Israel’s Foreign Ministry.

As far as the ambassadors are concerned, saying a few words in Hebrew as they present their letters of credence and the letters of recall of their predecessors is a courtesy, a sign of respect for the country in which they are serving and for its head of state.

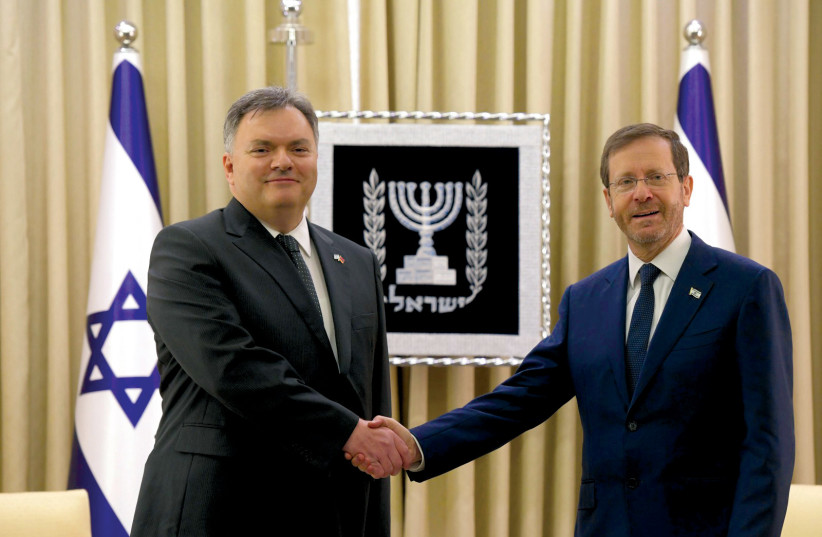

But it was definitely more than that in April, when Arman Akopian, ambassador of Armenia, continued to speak in fluent Hebrew after presenting his credentials. Herzog was amazed – even more so when he learned that Akopian, who is not Jewish, but is very familiar with Jewish religious customs and traditions, is also fluent in Arabic, Aramaic and Syriac. In fact, he has a PhD in Semitic Philology.

He was always interested in foreign languages, possibly more than he might otherwise have been if his father had been not a diplomat, serving as ambassador to Lebanon and to Greece. Much of Akopian’s childhood was spent in Lebanon, where there is a large Armenian Diaspora community. Among themselves, the Armenians – even those who have never lived in Armenia – speak Armenian, but in the street, everyone spoke Arabic. Several years later, when Akopian was a student at the university in Yerevan, he went on a year-long exchange trip to Jordan, where he improved his Hebrew by watching Israeli television.

Academically inclined by nature, Akopian was convinced that his future lay in academia. When head-hunted by Armenia’s Foreign Ministry and offered a job, he initially refused. But the Foreign Ministry was persistent and he finally consented.

Most Armenian diplomats are recruited from language schools, explains Armenia’s honorary consul in Israel, Tsolag Momjian, a third-generation Jerusalemite. There is a school for the languages of the Middle East and another for European languages. Armenia’s Foreign Ministry wants its envoys to be fluent in the languages of the countries to which they are posted, because that is a vital factor in the success of their work.

In 1991, after Armenia achieved independence, Akopian came to realize that what Armenia needed was soldiers and diplomats. “It didn’t need professors.”

Akopian spent a year at the Foreign Ministry, and in 1992 was part of the delegation of the president of Armenia during the latter’s visit to Egypt. Akopian’s academic training and experience stood him in good stead. He moved quickly through the ranks, and in 1995, at age 33, he was appointed head of the Foreign Ministry’s Middle East division.

In 1998, he paid his first and only visit to Israel as a member of the delegation of the foreign minister. Israel has changed greatly in the interim, he observes. “There’s a lot of construction and new buildings, much better infrastructure.”

Unlike other new ambassadors who spend a lot of time exploring the country, Akopian’s travels are mostly between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Of course, every ambassador who lives and works outside the capital travels to Jerusalem for meetings with the president, the prime minister, the foreign minister, members of Knesset and religious leaders.

Part of Akopian’s job is to maintain contact with the Armenian diaspora, and as most of the Armenian institutions in Israel are in Jerusalem, he spends a lot of time in the capital, while the embassy remains in Tel Aviv.

Asked whether the embassy not moving to Jerusalem is due to the close relationship that Armenia has with Iran, Akopian replies that Armenia’s bilateral relations are not contingent on third parties, though he does concede that the recorded history of Armenia’s relations with Iran goes back 2,600 years and can be found in stone, on parchment and on papyrus.

Moreover, unlike Israel, Armenia is a land-locked country, and it has only two ways to get to the sea: via Georgia to the Black Sea in the north, and via Iran to the Persian Gulf. So even though there have been ups and downs, Armenia must stay on good terms with Iran.

One of the ambassador’s first calls in the capital was to Armenian Patriarch Nourhan Manougian, the 97th Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem. The first was appointed in 638 CE.

Akopian describes himself as “the most secular person you’ve ever met,” but he takes a great interest in the languages, history, religion and customs of the peoples of the Middle East. In the course of conversation, when asked about Jesus and whether he would speak Hebrew if there was a Second Coming, Akopian said Jesus did not speak Hebrew because it was not a spoken language in his time. He spoke Aramaic.

Akopian, who has studied Christianity, Judaism and Islam in depth, thinks that “organized religion is a corporation,” adding: “All religions are created by man, so how do you know which is the right one?”

For all that, he doesn’t see anything strange about putting the Armenian Patriarch at the top of his must-visit list. “Can you imagine that an Israeli ambassador would not visit the chief rabbi of the country to which he is posted?” he asks. “An Israeli ambassador can’t ignore the Jewish community and its leaders, and I can’t ignore the Armenian community and its leaders.”

“An Israeli ambassador can’t ignore the Jewish community and its leaders, and I can’t ignore the Armenian community and its leaders.”

Arman Akopian

Another early visit that he made in Jerusalem was to the Hebrew University. He intends to visit all of the country’s universities, but the Hebrew University is special because it has an Armenian Studies program, and conducts an annual memorial event to honor the memories of the victims of the Armenian genocide. Akopian was among the speakers at this year’s commemoration.

Contrary to what is generally believed, in various talks with Turkish delegations with the aim of normalizing relations, Armenia, according to Akopian, has never made acknowledgment of the genocide perpetrated by the Turks against Armenians as a condition for normalization. Convinced that sooner or later relations will be normalized in conjunction with the changing world order, Akopian says that there are other considerations that must be agreed on as both countries move towards normalization: candid diplomacy, economic interests, opening of borders, direct flights, people-to-people contacts, and all the other usual agreements that make for good bilateral relations. “At this point talks between Armenian and Turkish delegations do not include recognition of genocide,” says Akopian.

This does not mean that Armenia has placed the genocide issue on the sidelines of history. “There’s not an Armenian child in the world who doesn’t know about it,” contends Akopian.

Israel recognized Armenia soon after it achieved independence in September 1991. So did Turkey, but whereas Israel entered into diplomatic relations, Turkey did not. But it seems that rapprochement between the two countries is closer than ever before. Previous attempts failed, because agreements were not ratified. But with Russia now perceived as the arch-enemy of Europe, talks are moving at a faster pace, and progress is being made. Current talks, at Armenia’s insistence, are without preconditions.

As for the genocide issue – despite Israel having not recognized it, Akopian credits Jews with bringing it to the attention of the world. It was first reported by Henry Morgenthau Sr., the German-born Jewish lawyer who was US ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1913 to 1916. Then in 1933, Austrian Jewish author Franz Werfel in his novel The Forty Days of Musa Dagh wrote about how the Armenians were shot, drowned, starved and tortured – sometimes in their own homes. The book inspired Jewish resistance against the Nazis, says Akopian.

Equally dismayed by the Armenian genocide, Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin was always just a step ahead of the Nazis when they invaded Poland. In 1940, he managed to get to Sweden, and in 1941 was permitted to enter America. He is credited with coining the word “genocide,” and writing a draft for the Genocide Convention Treaty, which was presented with the support of the US to the UN General Assembly.

In more recent years, the Armenian claim of genocide was supported by such international luminaries and experts on Holocaust history as Elie Wiesel and Yehuda Bauer, though noted historian Bernard Lewis dismissed it as just another episode in history.

Akopian understands that Israel’s reluctance to publicly recognize the Armenian genocide, even though there have been Israeli politicians and academics who have done so, is not based solely on political and diplomatic interests, but also out of a fear that it would deprive the Holocaust of its uniqueness. Akopian argues against that saying: “Every genocide is unique. You can’t compare one to another.”

Reiterating that the genocide acknowledgment is not a condition for a bilateral relationship, Akopian explains: “It’s not a political issue. It’s a moral issue, and one of historical justice.”

Getting back to his contention that bilateral relations are not influenced by third-party considerations, he is reminded that Armenia recalled its ambassador to Israel during the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan. “That’s because Israel supplied arms during a war,” Akopian retorts. Armenia had no objection to Israel selling arms to Azerbaijan in peacetime, but “the expectation was that during a war it would stop supplying arms.”

Until three years ago, Armenia did not have a resident ambassador in Israel. Akopian is the second, but Israel does not have a resident ambassador in Armenia.

The Jewish community in Armenia, though harking back 2,000 years, is tiny. Before independence, there were approximately 1,000, says Akopian, but afterward, many migrated to Israel and elsewhere. However, there is a rabbi and a functioning synagogue. According to Akopian, Rabbi Gershon Burstein emphasizes the importance of the synagogue being in full view of Turkey’s Mount Ararat, where according to legend, Noah’s Ark came to rest.

While in Israel, Akopian wants to maintain and advance the dialogue between the two countries. He also hopes to boost trade relations and people-to-people diplomacy, and even more importantly, humanitarian cooperation. He would like to see the resumption of direct flights that were stopped before the pandemic, and is looking for opportunities to establish direct links that will benefit tourism in both directions.

In this context, he is particularly interested in health tourism, and on the Armenian side can offer expert, affordable dental treatment. A lot of people come to Armenia for dental treatment, he says.

But where the greatest bilateral opportunities exist are in the fields of hi-tech and renewable energy. Armenia, like Israel, has few natural resources, but is very technologically advanced, and built its first computer in the early 1960s.

Though not religious, Akopian believes in karma. While standing at the entrance to the Jerusalem Waldorf Astoria, he was passed by one of the guests who happened to be Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu.

Perhaps that chance moment in Jerusalem was a mystical hint of future diplomacy. ■