“Without our traditions, our lives would be as shaky as – as a fiddler on the roof!”

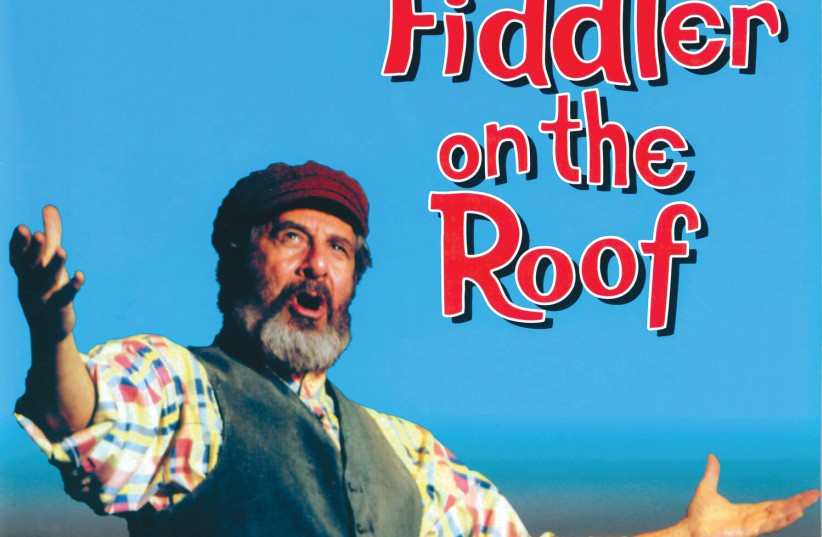

Fiddler on the Roof is back! A new production by Gadi Tzadka and his Teatron Ivri repertory company, starring and directed by Natan Datner, opened in Tel Aviv on July 3.

This beloved musical about life in Anatevka, a fictitious Russian shtetl, first premiered on Broadway on September 22, 1964. It ran for eight years and 3,300 performances, and was then made into a film, directed by Norman Jewison, in 1971.

How can one explain the universal popularity of a musical about poverty, God, tradition and the challenge of marrying three daughters in a Russian village? In 1964, the Beatles premiered on the Ed Sullivan Show and Fiddler competed with My Fair Lady. What was the appeal then of a musical about a Russian Jewish shtetl? And what is its appeal today?

Tradition, tradition! Tradition!

Tradition, tradition! Tradition!

Who, day and night, must scramble for a living,

Feed a wife and children, say his daily prayers?

And who has the right, as master of the house,

To have the final word at home?

I learned a great deal from Barbara Isenberg’s fine 2014 book, Tradition: The Highly Improbable, Ultimately Triumphant Story of Fiddler on the Roof – the World’s Most Beloved Musical. Much of what follows is based on Isenberg’s painstaking research.

What is the source of the title?

The famous paintings by Marc Chagall. His 1912 “Le Violoniste,” which is on loan to Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, shows a fiddler flying free in space; one of his feet is shown against the background of the roof of a farmhouse. But it could also stem from the painting “Green Violinist” , 1923-24, that features a violinist hovering above roofs.

According to Isenberg, there really was a fiddler on the roof – Chagall’s drunken violinist uncle. When virtuoso violinist Isaac Stern played over the initial film credits, he recounts that he purposely played slightly off-key – just as Chagall’s inebriated uncle would have. Now that’s being faithful to the source.

<br>Which Yiddish stories inspired it?

Sholem Aleichem’s beloved, timeless stories about life in the fictitious shtetl Anatevka. Born Solomon Rabinowitz, Sholem Aleichem wrote 300 short stories, five novels and several plays, all in Yiddish. He was commonly known as the Jewish Mark Twain.

When he came to the US, Isenberg recounts, Mark Twain met him and told him, “I wanted to meet you, because I understand I am the American Sholem Aleichem!”

Sunrise, sunset

Sunrise, sunset

Swiftly fly the years

One season following another

Laden with happiness and tears

What words of wisdom can I give them?

How can I help to ease their way?

<br>What is the historical context of Fiddler on the Roof?

The suffering and privation of Jews in Russian villages, resulting in massive migration to the US and Canada of three million Jews between 1881 and 1914. Among them: my grandfathers and grandmothers, mother and father, aunts and uncles.

The terrible massacre of Jews – men, women and children – in Kishinev in 1904 was a direct cause of my own family’s decision to emigrate. Those Jews who stayed died in the Holocaust.

<br>What explains the universal popularity of Fiddler on the Roof?

The librettist Joseph Stein attributes it to “the way the people of Anatevka harnessed their internal strength, dignity, humor and unique talent for survival.” Resilience in the face of crises is a recurrent, never-ending theme of life, then and now. It strikes a chord.

“Every time I do Fiddler, it coincides with something going on in the world. People losing their rights and losing their homes. That’s what makes it timeless.”

2012 producer

<br>Were the authors all Jewish? And was this no coincidence?

All three authors were Jewish. Stein, who wrote the text; Sheldon Harnock, who wrote the lyrics; and music composer Jerry Bock. All were descendants of immigrants from the Old Country.

Fiddler was a “valentine to our grandparents,” the three said. “I felt I had tapped a source that would not run dry, and I think that came from having nourished it without being able to express it all my life!” Bock wrote.

Norman Jewish directed the Fiddler film. In a documentary, Isenberg recounts, he is seen wiping away tears as the scene unfolds of Anatevka’s families prepare to leave the land they love. For him, too, Fiddler was intensely personal.

The power of Fiddler reached far beyond Jews – there have been 15 Fiddler productions in Finland alone. Why would Finns find pathos and inspiration in the story of Tevye the Milkman, and his tribulations about his family, God, the poverty-stricken shtetl and his unmarried daughters?

“Every time I do Fiddler, it coincides with something going on in the world,” a producer of a 2012 version explained. “People losing their rights and losing their homes. That’s what makes it timeless.”

In an interview with Channel 11, Datner reiterated this point, stating how relevant Fiddler was today in the face of the vast flow of five million refugees from Ukraine.

<br>Which actor played the quintessential Tevye?

Chaim Topol. The 1971 movie, starring Topol, has been seen by one billion people. Topol played Tevye on stage and screen, performing the role more than 3,500 times in shows and in revivals, through 2009.

A touching scene shows Topol addressing God directly. “Dear God,” Tevya says plaintively. “Did you have to send me news like that - today of all days? I know, I know, we are the chosen people. But once in a while, can’t you choose someone else?”

If I were a rich man

Ya ba dibba dibba dibba dibba dibba dibba dum

All day long, I’d biddy biddy bum

If I were a wealthy man

I wouldn’t have to work hard

Ya ba dibba dibba dibba dibba dibba dibba dum

Lord, who made the lion and the lamb

You decreed I should be what I am

Would it spoil some vast eternal plan

If I were a wealthy man?

Isenberg explains how this was set up. A piece of white cardboard with a Magen David on it was hung from the camera, so that Topol always looked to the same place when addressing, and arguing with, God.

I find this very personal and touching. My late grandmother Rivka used to say frequently zal got haltn meyn rekht hant (May God hold my right hand!) And she firmly believed He did.

For the Jews of the shtetl, God was personal – someone you talked to, argued with, even admonished. For them, God was imminent, not distant or remote.

<br>What is the enduring secret of <em>Fiddler</em>’s popularity?

The immense power of a universal narrative – a human story. Novelist Jean Paul Sartre once observed that people are tellers of tales: we live surrounded by our stories and the stories of others. Everything we see, we see through those stories, and we live our lives as if recounting a story, he said.

Economist Robert Shiller, a Nobel Laureate, took Sartre one step further:

“The human brain has always been highly tuned toward narratives, whether factual or not, to justify ongoing actions.”

Fiddler touches human hearts universally. That is why Fiddler is not really back.

Because it never left. And never will.

Through Fiddler, audiences down through the generations navigate rites of passage, through weddings, bar mitvahs, and deaths, joys and sorrows, triumphs and catastrophes.

Fiddler will continue to speak to future generations, as it has to past ones, with compassion and hope. ■

The writer heads the Zvi Griliches Research Data Center at S. Neaman Institute, Technion, and blogs at www.timnovate.wordpress.com