Rabbi Benny Lau is one of the most well-known and charismatic rabbis in both Israel and abroad. He has published deeply learned books on the prophets and on the biographies of the ancient sages, and he is an excellent teacher and lecturer.

Until recently, he served as senior rabbi of Jerusalem’s famous Ramban Synagogue, led the Israel Democracy Institute’s Human Rights and Judaism in Action project. He is currently director of the enormously popular 929 Tanach B’Yachad Bible study initiative, and is married to Noa with whom he has six children and three grandchildren.

Lau is also the scion of one of the finest rabbinic families in Israel, the Laus, and counts among his illustrious family his uncle Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau, a former Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel, as well as his cousin, Rabbi David Baruch Lau, the current holder of that title.

Bringing the Tanach back to the people

Yet all this is secondary to his main efforts to bring the Hebrew Bible – the Tanach as it is known in Hebrew – back to the people. If this seems a strange mission for someone who could easily have been the head of a rabbinical seminar (yeshiva gedola), it is not hard to find the reasons:

“Most Israelis over 60 studied Tanach in school. The majority of Israelis younger than that are still exposed to Tanach, so that in every house in Israel you will find a Tanach, whether the family is religious or not. The difference today is that the book is closed.”

Rabbi Benny Lau

“Most Israelis over 60 studied Tanach in school,” he tells The Jerusalem Report. ”The majority of Israelis younger than that are still exposed to Tanach, so that in every house in Israel you will find a Tanach, whether the family is religious or not. The difference today is that the book is closed.”

But surely Zionism, even in its secular dimension, was deeply embedded in the Tanach; how is it that Zionist Israel should have forgotten this fundamental text?

“When I speak about the Zionist movement, the part that brought them to establish the state in Zion was the dream of the return to Zion as written in the Tanach,” says Rav Benny (the nomenclature he prefers). “Every impulse of the movement was that it wanted to return to the land, the language, the culture, the geography, the history, as written in the Tanach. A people without a language, a culture, a geography and so forth would return to become ‘normal.’

“That was the engine that moved them to create their identity with the return to Zion. That was the generation that was. For the generation that I encounter, both them and their parents, the Tanach is no longer thought of as giving an identity. The people no longer know the Tanach. If they do know something about it, they think of the Tanach as chauvinist, as violent, a text that legitimizes racism, and the conquest of territory inhabited by others.

“If an Israeli aspires to be a democrat, and a liberal, how can he or she relate to the Tanach? Religious Zionists have made the Tanach the opposite of being the inspiration of the nation. The Tanach has now fallen into the hands of people identified with nationalism, and of ownership. They have ambushed the Torah. The population that I am trying to reach is that which has to be offered the Tanach anew, in order to bring them back to something that was lost. To give people the opportunity to encounter their tradition, but in an open way, open to dialogue, to questions, to challenges, to questions about conquest, democracy, liberal thinking, a tradition open to all languages and conversations.”

Creating the 929 Bible study initiative

The result of this analysis led Rav Benny to create 929, which corresponds to the number of chapters in the Tanach. It is the project to which he has devoted much of the last 10 years. He in fact gave up the Ramban Synagogue to turn his undivided attention to his innovative project.

“Truthfully, Ramban, despite its success, only frustrated me,” he admits. “I needed to break entirely from the rabbinic world and devote myself to 929. Today, I have a team of 25 people to help with the work. We have a budget of 10 million shekels a year, all from donations. There are 200 groups throughout the country. There is no end of work to do. Every day we have a virtual campus. I see it as a movement of return to the roots, to the sources.”

Virtual biblical study is made possible because of modern technology. Through the Internet, Rav Benny and his team are able to reach many more students than in an ordinary classroom – more than a quarter of a million in Israel alone, and many more abroad.

There are no exams, and no homework (unless it’s voluntary.) People join because they are attracted by the biblical narrative, its language, its stories, its teachings, and of course by the charismatic teacher who leads them day after day, week after week, through a text that has challenged the Jewish people and the world at large for three millennia.

THIS SHIFT away from a deeper knowledge of the Tanach, according to Rav Benny, could be found in the period between the Six Day War and the Yom Kippur War. “That is when a split became more apparent. You can put your finger on when it started. If you examine what happened to religious Zionism, you will find that it created a very specific type of politics around the land, and around the Torah. They would claim that something is written in the Torah, or that this is what the prophets really meant. This is their interpretation.

“Contrariwise, those who were not familiar with the Tanach pushed it away, sensing that it was irrelevant, or at least for them. So today a pupil in the general, secular educational framework will not have had more than an hour or two of Tanach studies from grade two on, and by the time he reaches secondary school, he knows nothing. If you ask him the names of the tribes – he won’t know, ask him about stories in the Tanach he won’t know, or ask him about the prophets, he doesn’t know. These are the basics. A pupil who has learned in a regular secular school knows nothing of his history, of the roots of his identity. I ask what will become of his children. What will become of the next generation. They have lost the thread.

“The goal I have is to awaken this connection, by way of the stories, by way of the language. This is not coercion, 929 is not a hegemony. We present many opinions. Our learning is a partnership for everyone. The message at the center of our program is that the Tanach is yours. It is an attempt to encounter the Israeli in his house, to help both children and their parents.”

By way of illustration, Rav Benny shows a video made by the 929 team, showing how dire the situation is. It features a young school pupil about to take an examination in Bible. But he realizes that he has had no time to learn about the subject matter of the test, which happens to be about King Saul. The video then shows actors taking him through a very truncated, if somewhat comical version of King Saul’s career. It is enough to provide the pupil with the knowledge he needs for his exam.

“That’s the level that we are at. It is very low, but that reflects our situation.”

Some religious individuals oppose his approach. They are upset that this is the way he does this work. He quotes non-Orthodox opinions and even non-Jewish ones! But it doesn’t worry him.

“It’s a free market. Someone who comes to the lessons comes of their own free will. We don’t force anyone.”

The Tanach is of course a complex text. It contains narratives, laws, prophecies and warnings, wisdom, literature and songs. It is not always consistent, and it leaves many questions unanswered. These are often left to the parallel Oral Torah to discuss and try to resolve. But Rav Benny is not focused on what the ancient sages have to say.

“It is 929, without the sages,” he explains. “We’re dealing here with the child who doesn’t know how to ask. Who is 929 aimed at? At youngsters from Holon and Bat Yam, Rishon Lezion, at eight million Jews in Israel. That’s the audience. I don’t go to the academy, nor to the yeshivot. I go to the people.”

Each group that meets under the aegis of 929 studies the Tanach according to their outlook.

“I don’t come along and say that this is the meaning of this passage. It is open to a wide variety of interpretations.”

What is it like to sit in on one of the lessons that Rav Benny is inspiring?

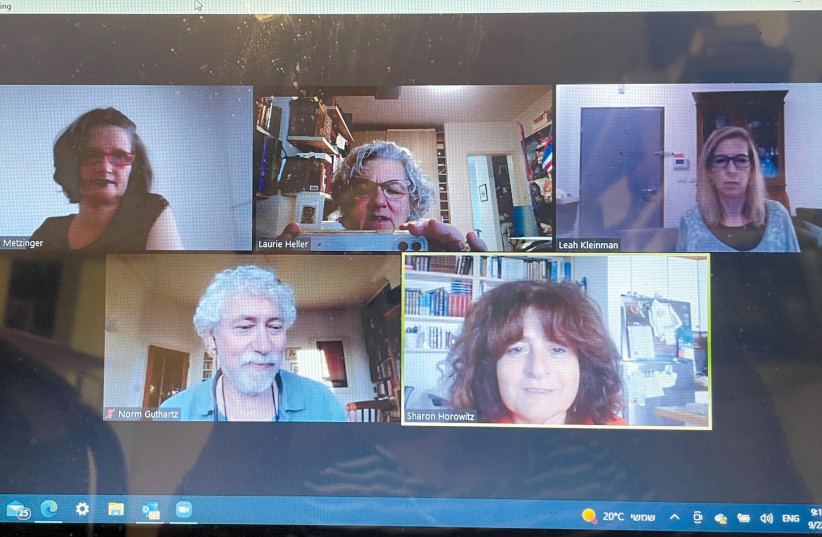

I did just that, via zoom, and saw how this group examined a particular passage from the Book of Numbers. One person had prepared the lesson while others weighed in with their own comments. Everyone was free to relate to the text according to their own understanding. In this way, the discussion, which took over an hour, revealed problems in the text as well as arguments between some of the traditional commentators, for example between Rashi and the Ramban. The discussion also examined the meaning or meanings of the Hebrew words used. This particular group was mainly “Anglo-Saxons” for whom Hebrew is not native, but one could feel the enthusiasm as they discussed the texts, very much bringing it alive and relevant to their own times.

One question remains for Rav Benny on the relevance of his teachings: what about the most outstanding issues in Israel today? Does that not concern him?

“I am not a public figure. I am no longer the head of a community, nor am I a political person. I am not part of the rabbinic establishment. I am not the address for a discussion of the situation in Israel. I teach Tanach, that is enough for me.”

Did he not want to influence others?

“In my own way, yes. But I won’t enter any other field. I have my private opinions but they will stay private. All questions about the future of the country or its politics do not interest me. To teach the Tanach, this is the goal I have set myself.”

LAU TURNS to those already versed in the religious texts: “Those who study it intensively are mainly the national religious group. They know their Tanach, they can quote it at will. They study it a lot. From the middle of the 1980s, they took over from the pioneering youth of the secular youth movements and became the movement of the religious youth movements. But in so doing they became fanatics.”

Rav Benny then observes something that might be a surprise to many. “The Haredim never study Tanach as such. If they learn it, it is via the Talmud, but they don’t study Tanach as an independent text.”

The success of Rav Benny’s project speaks for itself. Thousands of Israelis now come together to study what the late George Steiner called the book, and in its original language. The demand for these lessons has also burgeoned into English so that a much wider population of readers can benefit from the deeper meaning of this sanctified text. This bottom-up approach attracts more and more devotees.

Laurie Heller is one such student. She is part of an English language group that meets via zoom each week to discuss a chapter of Tanach. The group is able to read both Hebrew and English. Laurie, for example, studied at Yeshiva University in New York, and others in the group have varied backgrounds “We even had a female reform rabbi who was visiting Israel,” she recalls. “By studying a chapter at a time – unlike studying a weekly portion, which incorporates a number of chapters – we are able to go deeper into the text. We use all sorts of source texts. I am currently using Rav Steinsaltz’s commentary, though I have used more classical texts in preparing my study. What I gained from this study (and she is now into her third round) is the historical context of the Tanach. I have a timeline that I didn’t have before, and it makes everything clearer. There are also events for the groups such as a session at the President’s Residence, which is very encouraging, to know that the president of Israel is also behind this project.

“The English sessions are helped by the American-based branch of 929, so we don’t hear that often directly from Rav Benny, although from time to time he appears in English on Zoom. What is wonderful about the program is that it includes commentaries from all sorts of sources – whether Orthodox or not, or Jewish and non-Jewish. I value the diversity. If you want to live in the modern world, you have to know what other people say.”

Laurie, who emigrated many years ago from the US, is convinced that studying the Tanach in Israel is essential: “It’s the basis. If we don’t have that, why are we here?” ■