The Maccabiah Games, often referred to as the Jewish Olympics, take place in Israel every four years, two years before and two years after each Olympic Games. The ravages of corona resulted in a one-year postponement of the 2021 games, but nevertheless, Maccabiah 2022 attracted 10,000 athletes representing 62 countries, while 30,000 spectators watched the games.

Visiting US President Joe Biden, on an official visit to Israel at the time, made Maccabiah history by becoming the first US president to attend a Maccabiah opening ceremony.

One of the participating athletes, a member of the Australian delegation, was an old friend from Johannesburg whom I had not seen in 18 years, Trevor Wainstein, now a resident of Perth, Western Australia.

We arranged to meet at his hotel in Netanya, not far from the Wingate Institute, where many of the Maccabiah sporting events take place. Meeting him held a huge bonus for me, in that I met his roommate, Roman Gronsky, like Trevor, a senior or Master Swimmer. While Trevor was a member of the Australian delegation, Roman was head of the Czech delegation as well as a participating swimmer. A short chat with Roman during which he gave me snippets of his family history and his personal story convinced me that this man was a hero in the same mold as Yehuda Hamaccabi, whose name and heroic deeds are kept current by the Jewish games having been named as the Maccabiah, in his honor.

The story of Roman Gronsky

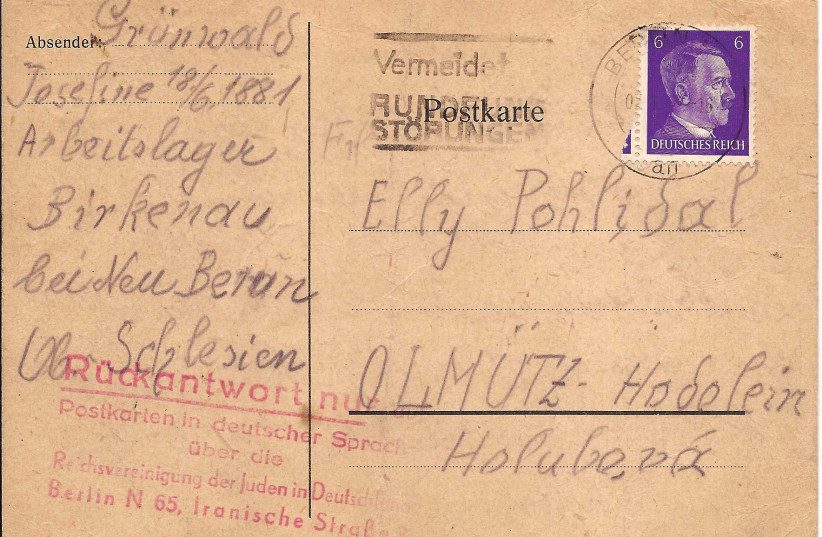

Roman Gronsky was born in 1950 in Olomouc, Czechoslovakia, then a satellite state of the USSR. His parents were Lothar and Eliska Gronsky, with Lothar having changed his surname to the less Germanic-sounding Gronsky after returning to Czechoslovakia following the end of World War II. Roman Gronsky’s grandfather, Nathan Grünwald, was born in the Floridsdorf district of Vienna in Austria, before moving 200 kilometers north to Olomouc in Moravia with his family in 1910 – hence the original Germanic family name of Grünwald.

Roman recounted the family history and general Jewish events in Olomouc in the period shortly preceding World War II, as well as his father’s activities during the war. Lothar (1914-1991) had read the warning signs inherent in the infamous Munich Agreement, and fled Czechoslovakia with two of his sisters in June 1939. The agreement had been signed in Munich on September 30, 1938, with Britain and France acceding to Hitler’s demand that Czechoslovakia cede the Sudetenland to Germany. The region was the home of many ethnic Germans, one of Hitler’s stepping stones leading to World War II.

The Grünwald siblings’ escape route took them to Tangiers in Morocco, and from there via Gibraltar to Britain. While his two sisters moved on to South America, Lothar remained behind in Britain where he joined the First Czechoslovak Armored Brigade Group, an element of the Free Czechoslovak Army, which was based at Leamington Spa in England.

Prior to fleeing from Czechoslovakia, Lothar Grünwald had qualified as a medical doctor at Charles University in Prague, which resulted in him being appointed as the senior physician of the brigade artillery unit. The Brigade Group was moved to Normandy in August 1944 and then on October 6 to Dunkirk, where it was placed under command of the First Canadian Army. It participated in the Siege of Dunkirk, which only ended after the official end of hostilities. During the period of the siege, the First Czechoslovak Armored Brigade Group suffered 668 casualties: 167 killed in action, 461 wounded, and another 40 missing who were believed killed.

Lothar Grünwald returned to Olomouc after the war to discover that he, his two sisters and his brother, Willie, were the only Jewish members of the family to have survived the Holocaust, the remainder having all been murdered. Willie, his non-Jewish wife and his family had found refuge from the Nazis during the latter stages of the war by hiding out for several weeks in the Slovakian mountains.

Prior to the Holocaust, Olomouc had a Jewish population of 3,000. Only 90 of them survived the wholesale Nazi slaughter of European Jewry.

The change of surname from Grünwald to Gronsky was no doubt fueled by the mass deportation of ethnic Germans who were spread all over eastern and central Europe. Referred to by the Nazis as Volksdeutsche, many of them were the descendants of Germans who had migrated eastward since the 16th century. Protecting the rights of ethnic Germans was one of Hitler’s pretexts in the events that led to World War II – a depressingly similar claim to that made by Russian President Vladimir Putin with regard to ethnic Russians as a justification for the current invasion of Ukraine.

The idea of expelling the ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe was mooted by Winston Churchill as early as 1942, drawing immediate support from the London-based Polish and Czechoslovak governments in exile. German-born historian Walter Schlesinger has posited that 12 million ethnic Germans fled or were deported from Eastern Europe, including Russia, between 1944 and 1950, with the vast majority finding new homes in Allied-occupied western Germany and Austria.

Back to Roman Gronsky

Growing up in Olomouc, Gronsky showed an early interest in swimming, and was a member of the Olomouc swimming club from age 13, remaining a member for the next 20 years. Having done his schooling in Olomouc, Gronsky completed his tertiary education at the Technical College in Brno, 80 kilometers from Olomouc, returning to his hometown where he found employment after his graduation. Gronsky was a keen sportsman, initially concentrating on swimming, but later participating successfully in several sports at the international level.

Disaster struck when Gronsky was involved in a major automobile accident in 1975, suffering serious injuries that resulted in the amputation of his right leg above the knee – which is much more debilitating than an amputation below the knee. Having recovered from the amputation and his other injuries, he returned to competitive swimming, now as a physically disabled athlete, and by May 1976 was vying for national honors, participating in the Czechoslovakian swimming championships for the disabled. Between 1976 and 1983 he won 27 national swimming championships in different strokes, as well as setting several new record times for amputees in his category. He earned selection as a member of the Czech team to participate as a swimmer in the 1980 Summer Paralympics in Arnhem in the Netherlands. This Paralympics saw Gronsky win two medals, silver in the 100m butterfly and bronze in the 200m individual medley. He also recorded the unofficial best time in the 400m freestyle for amputees above the knee, a record that stood for a number of years.

Following his retirement in 2018, Gronsky realized that he was good enough to compete against able-bodied swimmers in the masters or veterans category in his own age group, and in some cases even against younger swimmers. He participated in the 2019 European Maccabi Games in Budapest, achieving exceptional results. Competing against able-bodied swimmers, he won no fewer than eight medals at those Games, five gold (50m backstroke, 200m, 400m and 800m freestyle, and 200m individual medley) and three silver (50m and 100m freestyle, and 50m butterfly).

Swimming in the 70-74-year-old age group against able bodied swimmers during the Maccabiah Games in July, Gronsky won six medals – one gold and five bronze. This was in addition to heading the Czech delegation to the Maccabiah.

Roman found time between his work schedule and athletic commitments to marry Radmila Dostálová on November 16, 1979, with the couple becoming the proud parents of three daughters born between 1982 and 1991. Being a married man and a champion swimmer was not enough for our hero, he next took up Alpine skiing in 1981. He won the Czech Alpine skiing championship in his category for the disabled several times between 1981 and 1985, earning selection to participate in the 1984 Winter Paralympics, which were to take place in Innsbruck, Austria. One day before his departure for the Paralympics, the Communist authorities, for no apparent reason, advised him that he would not be allowed to participate, and to his great disappointment he was forced to withdraw from the team. Despite that setback, Roman continued Alpine skiing, having to sell his car in early 1990 in order to have money to participate as a member of the three-person Czechoslovak team to the World Alpine Skiing Championship, which took place at Winter Park, Colorado. Gronsky finished 13th in the slalom event.

From 1991 to 2010, Gronsky was the official coach of the Czech Winter Paralympic team, while also serving on the International Paralympics Committee as a member of the Technical Committee.

During 2001, Gronsky also took up competitive sports pistol shooting, winning several Czech national championships. These successes led to his participating in international shooting competitions in several European countries, the US and South Korea. He was a member of the Czech delegation to the 2013 Maccabiah as a pistol shooter, finishing fifth and sixth in the two categories in which he participated.

Gronsky headed the Czech delegation to the 2017 Maccabiah, and was also due to participate in the sports shooting events in 2021 when the games were canceled. Besides being an expert pistol shooter, Gronsky is a court-appointed expert on antique weapons, a subject that he has studied in great detail.

While participating in the various sporting disciplines and taking care of his family responsibilities to his wife and three daughters, Roman also forged a successful business career. Besides his sporting activities, in 1996 he joined Rotary International, a voluntary organization that brings professional and business people together to provide numerous communal services.

During 2006-2007, he served as district governor of District D2240 (Czech and Slovak republics) showing that his achievements in life have not only been sports related. He has been or still is active as a member of the Czech Maccabi Association, a veteran member of the Brno swimming club, a member of the Czech Association of Physically Handicapped Athletes, and a member of the Czech Shooting Association. Besides his other attributes, Gronsky is fluent in Czech, Slovak, Russian, German and English. During our chats, he related some of the incidents involving the Czechoslovakian Jewish community and the Holocaust, with particular reference to Olomouc.

The disastrous Munich Agreement gave Hitler carte blanche to invade and occupy Czechoslovakia, making the Jewish community there one of the first to taste the bitterness of Germany’s “Final Solution.” The Olomouc synagogue, completed in 1897, enjoyed a relatively short lifespan as it was razed and burnt to the ground by the Nazis on March 15, 1939, the first day of the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. Reputed to have been one of the finest and biggest in Czechoslovakia, the synagogue was designed by specialist synagogue architect Jakob Gartner and completed in 1897. Gartner, born in Prerov in the Olomouc district, had qualified as an architect in Brno, and designed a number of synagogues including those in Debrecen (Hungary), Trnava and Galgoc (Czechoslovakia), Targu Mures (Romania) and the Ujpest Synagogue in Budapest. The Olomouc synagogue was the only one to be totally destroyed, while the other synagogues designed by Gartner survived the war, with the vast majority of the congregants becoming victims of the Holocaust. Most of these synagogues are now listed as Synagogues Without Jews, surviving as memorials to the victims of the Holocaust.

Gronsky recounted how he had traced a Torah Scroll that had originally been in the Olomouc Synagogue to a congregation in California, and following negotiations for its return, the scroll had been repaired and was now back with the reestablished Olomouc congregation, with a house now serving as their synagogue. He told me the story of how 1,600 Czechoslovakian Torah scrolls had been offered for sale by the Communist Czechoslovak government in 1963. While he gave me the bare bones of the tale, I was intrigued by this information and conducted additional research into this tragic, but nonetheless fascinating aspect of Holocaust history.

Following the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, which began in March 1939 and the accompanying harsh anti-Jewish measures, a steady movement of rural Jewry to the larger centers began. Concerned members of the Prague Jewish community conceived a plan to save valuable Judaica, including Torah scrolls, left behind in the newly deserted synagogues, by transporting the items to Prague where they were cataloged and stored in the Central Jewish Museum. The Nazis took full control of the museum in 1942,, advising the Jewish community that all the items in storage would be returned to their owners when they returned from the “work camps” to which they had been sent. There were of course no work camps, but rather death camps, where estimates are that 236,000 Czechoslovakian Jews perished out of a pre-war population of 300,000.

Senior Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reich Security Main Office, had been appointed protector or governor of Czechoslovakia in September 1941. Acting on the advice of Adolf Eichmann, he devised a scheme whereby the Prague Jewish Museum would eventually morph into a “Museum to an Extinct Race,” the Jewish race, which would include a center to disseminate propaganda as well as to analyze and justify the “Final Solution.” Thus 1,800 Torah scrolls in the museum fell under Nazi SS control until the war ended, after which control resided with the newly established CSSR, the Czech and Slovak Socialist Republic, a fancy name for the communist government under Soviet control. The Torah scrolls were soon moved to another synagogue in the Michle district of Prague, where they were carelessly stacked and destined to slow decay and eventual destruction. The government decided during the late 1950s to “sell” the scrolls, stipulating that they had to be purchased as a job lot by a single buyer.

News of this strange offer by a government to “sell” property that it did not own excited much interest in Jewish circles, and very soon Ralph Charles Yablon (1906-1984), a solicitor, philanthropist and founder member of Westminster Synagogue in the United Kingdom, came to the rescue. He arranged to purchase the entire collection of 1,564 Torah Scrolls for £30,000 on behalf of the Westminster Synagogue.

The Memorial Scrolls Committee of the newly established Memorial Scrolls Trust Museum took charge of the scrolls and set about cataloging and recording the condition of each. The mammoth task of restoring the scrolls then began. Although Westminster Synagogue did not have a scribe qualified in the repair of Torah Scrolls, a near miracle occurred when an Israeli hassidic scribe on a visit to London appeared on the scene. He came knocking on the synagogue office door asking whether they had any Torah scrolls that needed repair. Mrs. Shaffer, the synagogue secretary, recalled his reaction: “I shall never forget the look of astonishment and awe on his face when he saw those three rooms stacked to the ceiling with sifre Torah.” Scrolls from the collection have since been repaired and sent out on loan to Jewish communities across the globe, including the Torah Scroll found by Gronsky in California so many years later. The subsequent return of the Torah to its former home in Olomouc, closed the circle on the remarkable travels of that particular scroll. ■