Two notable scholars – Richard I. Cohen, an emeritus professor of Jewish history at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; and Mirjam Rajner, an associate professor and chair of the Department of Jewish Art at Bar-Ilan University – have join forces to produce a compelling study of Samuel (Schmul) Hirszenberg, a Polish-Jewish painter active in the late 19th and early 20th century who died in Jerusalem.

The book is titled Samuel Hirszenberg, 1865–1908, A Polish Jewish Artist in Turmoil and was published in 2022 by The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. The book is an appreciation of the artist as a painter of both Jewish and general subjects, as well as the story of an iconic figure in an environment undergoing rapid shifts in the Jewish world and the world at large.

Indeed, the time of Hirszenberg’s relatively short life – the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – was a period of enormous changes in the social world of the Europe that the artist traversed.

Iconic artist Samuel Hirszenberg

Brought up in a large and traditional Yiddish-speaking family in Eastern Europe, Hirszenberg lived and worked in Lodz and Lisowice (Poland), Munich, Rome, Krakow, Paris and Jerusalem. He threw off his religious upbringing early on and became deeply attached to Poland, its language and culture. Nevertheless, he retained a strong, if ambivalent, attachment to his Jewish roots as witnessed in some of his major works, as well as his travels.

Alongside his commissions to paint portraits and his own predilections to paint landscapes and nudes in bucolic surroundings, he painted the world of the Jewish community as he saw and remembered it. It is a world to which he no longer felt attached, yet derived inspiration from as an artist. The Jewry that he portrayed is more or less the opposite of the joyous, fecund world he showed in his other paintings. His Jews are invariably serious, not to say solemn, creatures, cast out of regular society and wandering in an alien and often hostile world.

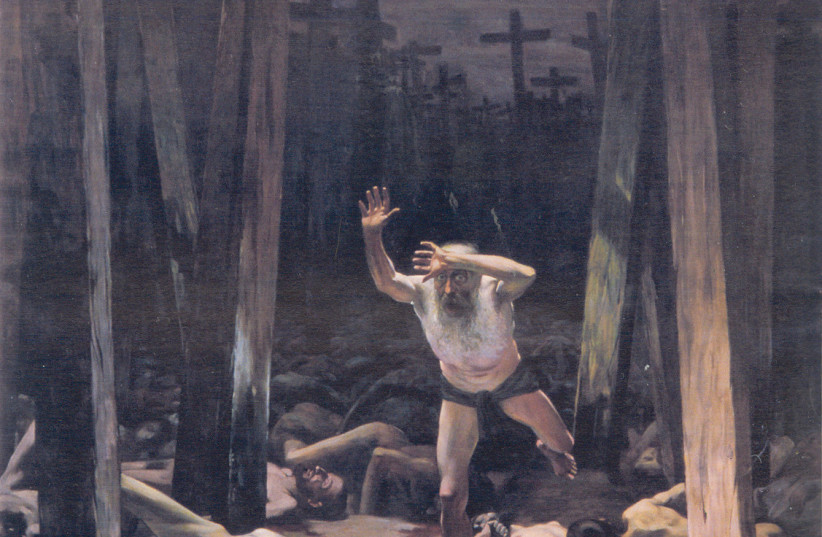

The Wandering Jew, for example, a huge canvas now displayed in the Israel Museum, depicts a semi-naked man running through a valley of crucifixes, with the dead bodies of Jews lying to his left and right. Of this startling picture, the authors write: “He raises one hand while covering his forehead, with the other in a gesture to avoid the sharp light that blinds him. He leaves the dark, eerie field as a solitary figure with no possession and without a clear sense of the road that lies ahead.”

The fact that the painting predates the Holocaust by some 40 years lends it perhaps even greater, prescient power. It was Christian Europe that left, for the most part, the Jewish people naked and powerless within its host countries. The painting clearly shows how antisemitism was thriving well before the events of World War II.

Another painting, Exile, depicts the Jews as a people driven into permanent wandering from place to place, here made even more depressing by the snow that accompanies their forlorn journey. Although the whereabouts of this particular painting are unknown, it appears that the individual figures were taken from Hirszenberg’s extensive sketch books over several years. These were real people suffering from real misery wherever they went.

Another large painting, The Black Banner, now on display in the Jewish Museum in New York, purports to show the funeral of a hassidic rabbi but simultaneously refers the viewer back to The Wandering Jew in the depiction of “the fearful eyes and bedazzled look among the mourners.” This painting “highlights Hirszenberg’s merging of the symbolic with the realistic, and alludes once again the angst of life in exile and eternal wandering,” the authors say.

These were deeply felt works, despite the fact that the artist had moved away from any religious commitment. He saw himself as a secular Jew who was nevertheless attached to his people, to their myths, as well as to their historical reality, as grim as it might sometimes be.

One well-known visitor to Hirszenberg’s studio in Lodz made the following report, emphasizing this aspect of the artist’s oeuvre:

“Upon entering Hirszenberg’s studio, you feel that you are first and foremost in the space of a Jewish artist; a good Jew who cares deeply about the problems of his people, and who lives in its present and breathes its past. Ragged and unremarkable figures, his co-religionists – perhaps trivial at first sight, but all radiating solemnity and a somewhat dolorous charm – gaze at you from the walls.”

“Upon entering Hirszenberg’s studio, you feel that you are first and foremost in the space of a Jewish artist; a good Jew who cares deeply about the problems of his people, and who lives in its present and breathes its past. Ragged and unremarkable figures, his co-religionists – perhaps trivial at first sight, but all radiating solemnity and a somewhat dolorous charm – gaze at you from the walls.”

Visitor to Samuel Hirszenberg's studio

Simultaneously, Hirszenberg was being commissioned by wealthy Jewish entrepreneurs in the thriving city of Lodz. One of them, Izrael Poznanski, asked the artist to decorate his palace with some huge wall stucco paintings, with their overt references to ancient Greek mythology.

Hirszenberg knew about, and was a witness to, the major changes in the art world at the time. He lived for a while in the Paris of early Picasso, Braque, the post-Impressionists and Art Nouveau. Nevertheless, he retained his more classic approach to his subjects and techniques, although integrating some of the new styles of paintings into his own.

One indication of where he was emotionally and intellectually could be inferred from the last major painting he executed in Krakow (Poland) titled The Excommunication of Spinoza. The authors make the following comment on this powerful rendition from Jewish history: “This large canvas addressed openly the ‘Jewish drama’ that preoccupied Hirszenberg throughout his artistic career: the confrontation between tradition and modernity.” It is fairly obvious which side Hirszenberg is taking in the conflict between Spinoza and the haranguing, Orthodox onlookers.

The tension between new and old may help explain his last journey, where he accepted an invitation to teach at the newly founded Bezalel Academy of Art in Jerusalem. Even though he appears not to have been a Zionist, he was attracted by the idea of the Middle East, its people and its landscapes. He arrived in Jerusalem already a known figure in the art world. He was met by Bezalel founder Boris Schatz and the Bezalel students, and an article welcoming him was published in Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s newspaper, Hashkafa.

The difference between the dull, gray skies of Europe and the brightness of the Mediterranean sun had an obvious effect on Hirszenberg’s painting. In this he was following the way of his fellow teachers – Lilien, Schatz and Ze’ev Raban – who were similarly drawn toward the landscape and portrayals of local Oriental Jews and Arabs. Hirszenberg’s portraits of his new neighbors, as well as his landscapes, show how easily he absorbed his new environment. Unfortunately, many of his original paintings and sketches from this period are lost and are available to us only through reproductions.

Hirszenberg died in 1908 at age 43, less than a year after arriving in Jerusalem, his rich career cut short by illness. Nevertheless, there are enough of his extant works to underline his importance in art history generally and Jewish art history in particular. His is a fascinating reflection of conflicting forces that still echo among Jewish artists today – an artist of the general world, as well as someone continuing in a tradition of Jewish art in all its many facets.

Cohen and Rajner have made this figure, with all his complexities and inner tensions, accessible to a wider audience. The combination of historian and art expertise allows Hirszenberg to emerge against his contemporary background, while the detailed analysis of his works reflects the power and grace of the artist at all stages of his creative life. ■