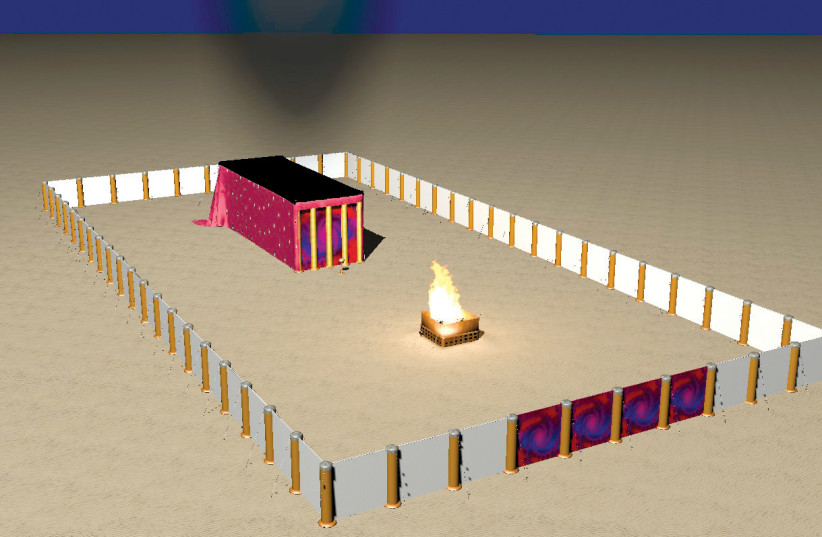

Parashat Vayakhel consists of 1,558 Hebrew words and 122 verses. All but 30 of its words and three of its verses talk about the building of the mishkan, the portable sanctuary where the Israelites could perceive and experience God’s presence during the exodus years. That the mishkan is the focus of the parasha speaks of the importance of the mishkan. By extension, does that small number of words and verses in the remainder of the parasha signal something minor?

The answer is the opposite, as those three verses help us understand one of the most important concepts in Judaism: How do we define work/melacha on Shabbat? Earlier, during the revelation on Mount Sinai, we read in the fifth of the Ten Commandments/Sayings (Exodus 20:8-11):

“Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, neither you, nor your son or daughter, nor your male or female servant, nor your animals, nor any foreigner residing in your towns. For in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but he rested on the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy.”

While the text is emphatic about not working on Shabbat it does not define work. This is problematic to say the least for anyone who wishes to follow this foundational commandment of Judaism. All of this brings us to this week’s parasha (Exodus 35:1-2):

Moses assembled the whole Israelite community and said to them, “These are the things the Lord has commanded you to do: For six days, work is to be done, but the seventh day shall be your holy day, a day of Sabbath rest to the Lord… ”

The last third of the book of Exodus is concerned with the mishkan. The commandment not to work on Shabbat placed in the midst of that description stands out and is noted. There is a similar injunction not to work on Shabbat in last week’s parasha (Exodus 31:12-17) also inserted in the mishkan narrative. That the injunctions not to work on Shabbat are surrounded by lengthy descriptions of the construction and furnishing of the mishkan did not escape the rabbis. They discuss (Shabbat 49b):

“The primary categories of labor (prohibited on Shabbat) are forty-less-one; to what does [this] correspond? Rabbi Hanina bar Hama said to them: They correspond to the labors in the tabernacle.”

Related, Rashi comments, “You shall keep My Shabbatot and venerate My Sanctuary/Mikdash; I am the Lord,” (Leviticus 19:30) – “Even though I have commanded you to build the Mikdash, nevertheless you must keep My Shabbat, for the building of the Mikdash does not override Shabbat observance.”

IN THE minds and thinking of the rabbis, we had already been introduced to the concept of Shabbat, earlier on Mount Sinai. So, if this was being commanded again it must be to teach something further about Shabbat – in this case, the definition of work, since our sentence here about Shabbat resides in a sea of words and Torah portions about the construction of the Miskhan. From examining those activities, the rabbis derive 39 tasks (Mishna Shabbat 7:2) that become the core definition of work prohibited on Shabbat. That list is also expanded by the rabbis to include other actions resembling the 39 derived from the fabrication of the mishkan.

In looking at the 39 activities, Rabbi Sara Cohen and environmental scholar Jeremy Benstein note the taking of raw materials from the environment and changing them to benefit humans. This observation echoes the words of Rabbi Mordechai Kaplan: “In the light of these explanations, the function of the Sabbath is to prohibit people from engaging in work which in any way alters the environment.”

In his insightful analysis of melacha, Dr. Dayan I. Grunfeld adds that melacha can be understood as “an act which shows man’s mastery over the world by the constructive exercise of his intelligence and skill.”

In other words, one critical aspect of Shabbat is: Leave the environment alone. Combining Shabbat and many of the Jewish holidays, we see for more than one-seventh of the year we are told to let the environment be. It is a profound lesson when it comes to our relationship with the environment.

In addition, Nechama Leibowitz points out the words used to describe the construction of the mishkan are also used in the description of Creation; the mishkan can be understood as symbolic of Creation itself, a Creation for which we partner with God in fashioning and preserving. That point is echoed in the account of Creation where everything created before humans is called by God “good,” reminding us of the intrinsic value of all within the environment that was created before us. The “very good” after we were created is not to say the world was created for us, but that we humans happen to be the final piece of the magnificent puzzle. The totality of the diversity of everything is “very good.”

Too often, when we think about Shabbat we focus on what is not allowed. But there is another profound lesson here, as well. While the 39 categories tell us what not to do on Shabbat, they also inform us what to do on the other six days of the week. And what is that? Build a mishkan, a dwelling place for God in the world, and by extension, as we see above: contribute to the construction of the world.

This is our charge – to understand that no matter what work we are engaged with, we should try to elevate it in our eyes – to see our work as an important donation to the tapestry of our world. That work becomes holy when we act with truth, compassion, love and humility. We must release the sparks of holiness contained in what we do, as we work for six days and then rest on Shabbat.

The writer is rabbi emeritus of the Israel Congregation, Manchester Center, Vermont, and a faculty member of the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies and Bennington College.