Among the millions of items in the National Library’s collections are also hundreds of Esther scrolls - the largest in the world. Some of which are particularly ancient and rare, that tell the story of Jewish communities throughout Europe and Eastern Jewry. As the nation marks Purim, the National Library provides a rare glimpse into part of the collection.

The prestigious relic from the 15th Century: The Esther scroll of Spanish Jewry

One of the world’s oldest known Esther scrolls (also known as a “megillah“) has recently been gifted to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, home to the world’s largest collection of textual Judaica.

Esther scrolls contain the story of the Book of Esther in Hebrew and are traditionally read in Jewish communities across the globe on the festival of Purim, which will take place on February 25-28 this year.

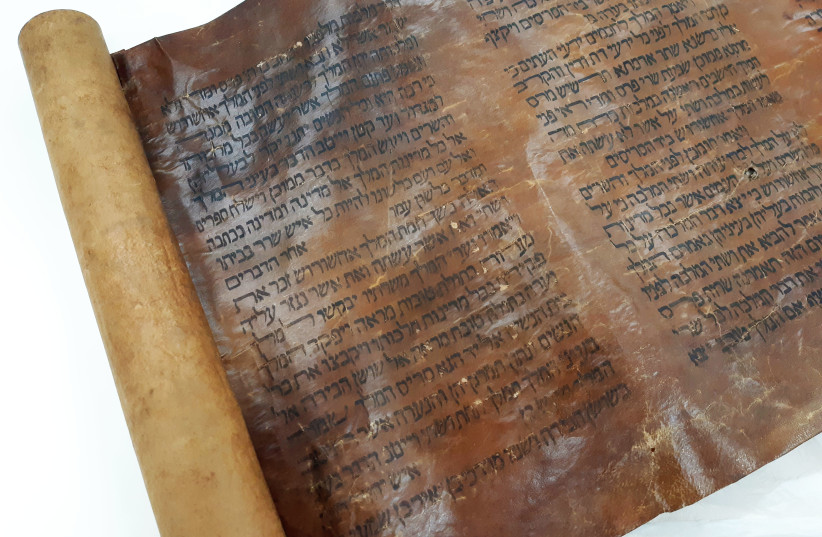

Scholars have determined that the newly received Esther scroll was written by a scribe on the Iberian Peninsula around 1465, prior to the Spanish and Portuguese Expulsions at the end of the fifteenth century. These conclusions are based on both stylistic and scientific evidence, including Carbon-14 dating.

The megillah is written in brown ink on leather in an elegant, characteristic Sephardic script, which resembles that of a Torah scroll. The first panel, before the text of the Book of Esther, includes the traditional blessings recited before and after the reading of the megillah, and attests to the ritual use of this scroll in a pre-Expulsion Iberian Jewish community.

According to experts, there are very few extant Esther scrolls from the medieval period in general, and from the fifteenth century, in particular. Torah scrolls and Esther scrolls from pre-Expulsion Spain and Portugal are even rarer, with only a small handful known to exist.

Prior to the donation, this scroll was the only complete fifteenth century megillah in private hands.

According to Dr. Yoel Finkelman, curator of the National Library of Israel’s Haim and Hanna Salomon Judaica Collection, the new addition is “an incredibly rare testament to the rich material culture of the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula. It is one of the earliest extant Esther Scrolls, and one of the few 15th century megillot in the world.”

The Esther Scroll of Amsterdam That Damned the Enemies of the Jews

This was what happened when the Purim merriment of the Jews of Amsterdam mixed with a desire for revenge against the Spanish.

One of the things the Jewish people are good at is storytelling. Every year on every holiday we tell the stories of persecution, courage, and consequence that happened to every generation of Jews wherever they were. And that includes tying events described in the Scroll of Esther and the holiday of Purim itself to more contemporary events. For our purposes, the turn of the 18th century will count as “contemporary”.

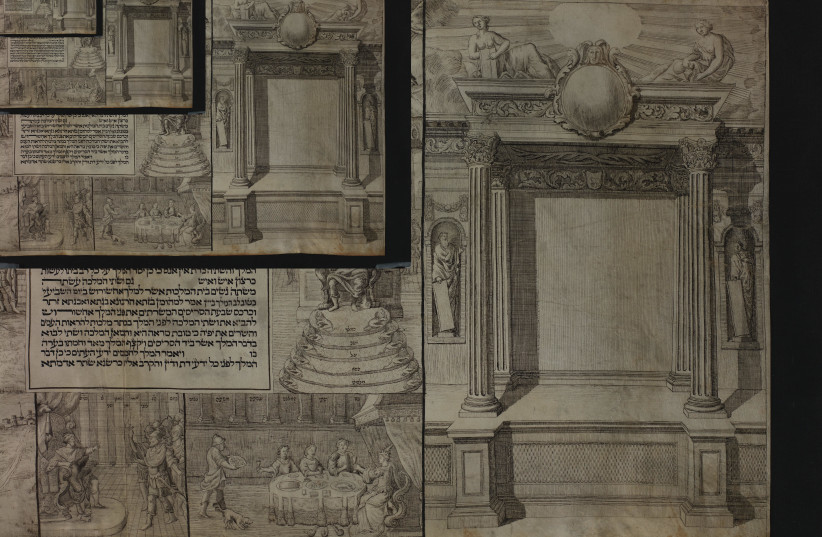

It is through the illustrations found in a Scroll of Esther manuscript drawn and copied around 1700 that we see this direct tie between the ancient telling of the persecution of Jews in Persia and the more recent persecution of Jews by Catholic Portugal and Spain.

The Jewish quarter of Amsterdam was established in the 17th century by Ashkenazi and Portuguese communities. This particular matter focuses on the Portuguese community.

The descendants’ of the Jewish conversos who emigrated en masse from Portugal to Amsterdam throughout the 17th century had not been permitted to keep and practice their ancient religion. In their new Dutch home they wished to return to their Jewish faith.

One way back was through the holidays. Purim was a good start considering joy and merriment are the main aspects of the festival, along with the commandments of drinking and eating, and the celebration of surviving near extermination; it is a story of Jewish continuity while in the diaspora.

And so the Jewish community of Amsterdam commissioned an artist to illustrate a contemporary Scroll of Esther – telling the story of surviving the evil Persian Haman, as well as exacting revenge upon the more recent Portuguese ‘Hamans’.

The unknown artist illustrated unforgettable scenes. The opening page features two semi-nude women, hinting to the readers that they are going to be reading a theatrical play. The artist also illustrated the more violent and gory scenes of the story. But one scene truly surpasses the rest. In order to emphasize the fate of those who persecute the Jews, as well as to kiss up to the Dutch who defeated Spain in their War of Independence (and not forgetting that the Spanish had expelled the Jews 150 years earlier) – the artist decided to draw what can only be described as a circumcision assembly line. On this assembly line are three Gentile men suffering the pain of circumcision while the mohels seem quite at ease. The scene accompanies the verse: “And many of the people of the land professed to be Jews, for the fear of the Jews had fallen upon them.”

The Scroll of Esther is the only book in the Hebrew Bible in which God’s name is not mentioned even once. This fact did not stop the artist from again linking elements of the story to his own time period. In one of the illustrations, we see Jews kneeling and thanking God in a synagogue, the style of which was typical of the Portuguese Jewish community in Amsterdam. And the victorious 18th-century Jews of Amsterdam could finally make time for merriment, joy, and a good meal.

Purim Special: The ‘Azores Megillah’

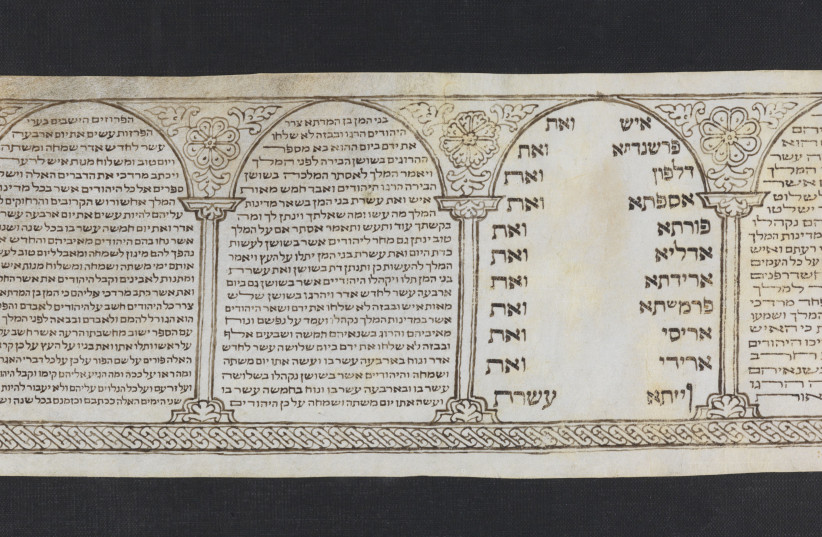

The Azores Megillah at the National Library of Israel provides beautiful and early textual evidence of Jewish life in the Azores.

Measuring just 12.7 cm (5 in) in height, this exquisite scroll was written in the 19th century and dedicated to David Sabach [i.e. Sabath], a well-known member of the Azorean Jewish community and a man eulogized as having great Torah knowledge. He was born prior to 1847, probably in Sao Miguel, Azores and died in 1915 in Portugal.

The Azores Islands belong to Portugal and are located some 1500 km (950 miles) from Lisbon. Jews fleeing persecution fled there in the 16th and 17th centuries, though they left no known written record of their Jewish lives or practices. The first written record we have of Jewish life on the islands comes with the arrival of Moroccan Jews in 1818. By the mid-19th century, the Azorean Jewish population was about 250, most of them living in Ponta Delgada, on Sao Miguel Island. The historic Shaar Hashamayim Synagogue in Ponta Delgada has recently been renovated and converted into a museum about the history of Azorean Jewish life.

The Azores Megillah came to the National Library of Israel as part of the famed Valmadonna Trust Library, the finest private collection of Hebrew books and manuscripts in the world, which was purchased jointly by the National Library of Israel and archaeology, book and Judaica collectors Dr. David and Jemima Jeselsohn through a private sale arranged by Sotheby’s.

The Valmadonna collection is currently being digitized and it will be showcased in the National Library of Israel’s landmark new building, designed by award-winning architects Herzog & de Meuron, and currently under construction in Jerusalem.