Rabbi David Weiss Halivni, a theologian, beloved teacher and pioneering and sometimes controversial scholar of Talmud, died Wednesday at age 94 in Israel.

A Holocaust survivor, Halivni earned his doctorate and taught for many years at the Conservative movement’s Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, until leaving the institution in 1983 over its decision to ordain women rabbis. He later became dean of the rabbinical school of the Union for Traditional Judaism, a movement created by rabbis and scholars who similarly broke with the Conservative movement.

“He genuinely loved teaching Torah to such a degree that he felt we were helping him by being willing to learn from him.”

Elana Stein Hain of the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America

Halivni's controversial approach to Talmud

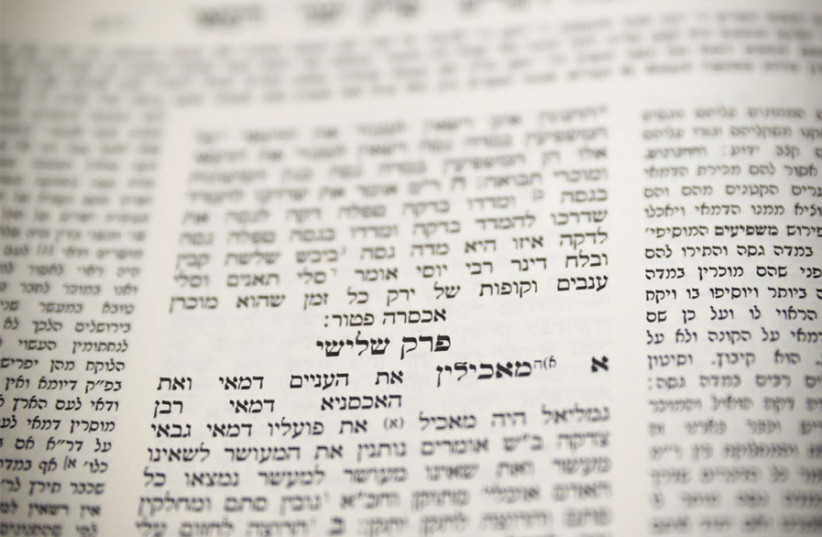

He is perhaps best known as a champion of the “source-critical approach” to studying Talmud, treating the vast compendium of Jewish law and lore not as a seamless, unassailable work but as a tradition layered with variant readings and textual strata altered in transmission.

“For a thousand years, Jews studied the text and did not question its authenticity as a faithful record,” Halivni told an interviewer in 1977. “Statements were attributed to scholars living 2,000 years earlier, but rarely did anyone ask how these statements had come down to the present.”

But while traditionalists felt his approach, laid out in his multi-volume opus “Mekorot u’Mesorot,” or “Sources and Traditions,” trampled on the “domain of the divine,” Halivni insisted his work was in line with an unbroken chain of rabbis and scholars who contributed to what he considered a living canon of Jewish text.

“Our work in life is to make room for God’s presence in all our endeavors,” he said. “God’s revelation needs constantly to be reinterpreted and concretized, for man’s expression of God’s law is ambiguous.”

David Weiss was born in 1927 in Kobyletska Poliana, Czechoslovakia (now Ukraine), but was raised in Sighet, Romania — the same hometown as Elie Wiesel, who was his life-long friend. Recognized as a “boy genius,” he was ordained as a rabbi at 15. When Nazis seized the town in March 1944, he was sent first to Auschwitz, and then to the Wolfsberg and Ebensee (Mauthausen) concentration camps. He was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust.

In his 1996 memoir “The Book and the Sword” and the 2007 book “Breaking the Tablets,” Halivni laid out his justification for observing Torah and praying to God despite the horrors of the Holocaust. He rejected suggestions that the Holocaust was divine punishment for the Jews’ purported sins. Rather, he wrote in “Breaking the Tablets,” God “restrained himself from taking party in history and gave humanity an opportunity to display its capacities, for good and for evil. It is our misfortune that, in the time of the Shoah, humanity displayed its capacities for unprecedented evil.”

Halivni — a Hebraized version of his last name, which he adopted to distance himself from German officers also named Weiss — became a naturalized US citizen in 1952. He received his doctorate from JTS in 1958 and went on to teach at JTS, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Bar-Ilan University and Harvard Law School.

Associated with Columbia University for 35 years, he taught there full time starting in 1986 and retired in 2005.

He was also the longtime head of Kehilat Orach Eliezer, an Orthodox minyan in Manhattan. Although his approach to Jewish text aligned closely with the Conservative movement’s, the women’s ordination debate — and especially a decision-making process he felt was flawed — proved a bridge too for a scholar raised and educated in Orthodox traditions. In his letter of resignation he wrote: “It is my personal tragedy that the people I daven [pray] with I cannot talk to and the people I talk to I cannot daven with. However, when the chips are down I will always side with the people I daven with. For I can live without talking, I cannot live without davening.”

A lasting legacy

Halivni was known for his devotion to his students, and tributes poured in upon news of his death.

“He genuinely loved teaching Torah to such a degree that he felt we were helping him by being willing to learn from him,” recalled Elana Stein Hain of the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America, in a Facebook post. She said Halivni encouraged her to earn her doctorate in religion from Columbia University.

“Rav Halivni was a visitor from another world — a world of Eastern European learning, of concentration camps, of mid-20th century JTS,” wrote Laura Shaw Frank, director of contemporary Jewish life at the American Jewish Committee, also on Facebook. “And Rav Halivni was very much of this world, a visionary who pioneered academic Talmud study and pushed for the expansion of women’s learning and leadership in Orthodox Judaism even while insisting on fealty to the halacha [Jewish law] and masoret [tradition] he held so dear.”

In 1996, Halivni traveled to the University of Nanjing where he helped start the first center for Jewish studies in China and addressed the country’s first academic meeting of Chinese, Jewish and Israeli scholars.

“I feel a kinship with the suffering of many Chinese, in their struggle to survive,” he said in an interview ag the time.

After his retirement, he moved to Israel. He taught at Hebrew University and Bar Ilan University well into his 90s. In 2008, Halivni was awarded the Israel Prize for his landmark research on the Talmud.

“Though perhaps small in stature, Prof. David Weiss Halivni was an intellectual giant, a legend in his own time, and a dear friend of the National Library of Israel, where he was truly a fixture, spending thousands of hours immersed in research and conversation with fellow scholars and students,” read a statement by the National Library of Israel.

Halivni’s fluency in a wide range of Jewish texts and thinkers was stunning, according to many of the people who studied with him.

“It was like glimpsing into, simultaneously, Bavel, Lucena, Worms, Lublin, Cairo, Jerusalem, etc. … all at once, but precisely extracted, one from the other,” Rabbi Aaron Alexander of Adas Israel Congregation in Washington, D.C., wrote on Facebook about the experience of sitting in on Halivni’s Columbia Talmud course. He was referring to historic sites of Jewish study. “And he did so with a humility that was immediately and obviously 100% genuine.”

Halivni was predeceased by his wife Zipporah Hager, who taught comparative literature at City College of New York. They raised three sons: Baruch Weiss is an attorney in Washington, D.C.; Shai Halivni is an attorney in Illinois; and Rabbi Ephraim Halivni lives in Israel, where he works at the Academy of the Hebrew Language.