The book of Genesis ends dramatically with Joseph promising his brothers that God will surely remember them and bring them back up to the Promised Land.

Decades later, as the book of Exodus begins, the Hebrews are enslaved and seem to be far from God.

The reintroduction of godly consciousness is done gradually. The first “to see God” are Shifrah and Puah, the midwives – unclear if they are Hebrews or not. The next reported seeing of God occurs more than 80 years later, with God’s revelation to Moses at the burning bush.

The 10 plagues, we are told, are designed to broaden godly consciousness to both the Hebrews and Egypt, as well as to instill the counter-universalism notion “that you would know that God discriminates between Egypt and Israel.”

Indeed, such godly consciousness is accepted by the Egyptians. Shortly thereafter, in the Song of Sea that marks the exodus from Egypt, we are told that such godly consciousness was expanded to the other nations as well: “Then the chiefs of Edom were frightened; the mighty men of Moab, trembling taking hold upon them; all the inhabitants of Canaan are melted away.”

The Hebrews sing: “The Lord shall reign forever and ever.”

And so “mission accomplished” – a global acceptance of monotheism, of God’s rule (“Aleinu Le’shabeah”). End of history?

Not yet.

First reversal of universal acceptance of God

The Hebrews in the desert kept their faith in God. The “remainers” who wanted to go back to Egypt based their arguments primarily on questioning if Moses really represents God.

But the unexpected 40 years in the desert led the surrounding nations to disbelieve in God, or at least to the conclusion that God is no longer with the Hebrews. The chiefs of Edom were no longer afraid and refused to let the Hebrews pass through; and the inhabitants of Canaan (Arad) were no longer melting, and attacked the Hebrews.

In this regard, the sin of the 10 spies tends to be grossly underestimated in biblical teachings. The extra 38 years in the desert caused by their actions were not only harmful to Israel but also to instilling global recognition of God. (The reverse of “Aleinu Le’shabeah”).

Just as the growing global faith in God likely contributed to the Hebrews’ own faith a few decades prior, so did the reverse: The global disbelief likely contributed to the emergence of a defining ethos of the Bible – the battle between monotheism and paganism. As the biblical period ends, this debate remains inconclusive.

But then something astonishing happened. Invaders from Europe – the Greeks and then the Romans – tried to negate Judaism and monotheism and instill their European values of universalism and paganism. But instead, after some time, they accepted Judaism’s core of monotheism. This was spread to pagan Europe in the form of Christianity. A few centuries later, monotheism was spread to the pagan Middle East in the form of Islam.

And so by the seventh century, for the second time in history much of the world was in unison in its belief in God.

While the first unison lasted for just a few short decades after the Exodus, this time it lasted for more than a thousand years. Europe adopted the governing principle of divine-right monarchy: The power comes from God, and He gives that right to kings.

During the Exodus, the global acceptance of God likely contributed to the Jews’ own strengthening of faith. So did it this time. As they went into exile for 1,800 years, the religious aspect of the Jewish nation-religious – rabbinic Judaism – became the anchor of Judaism (Judaism 2.0), and there was no more reported paganism in Judaism.

But then…

Second reversal of universal acceptance of God

Two revolutions in the 18th century shook the system of divine-right monarchy. One was the American Revolution, which did not negate the divine, but the notion that God gives the right to the monarchs. The right was given in America to the people – conceptually a divine-right Republic: “We the People,” “One nation under God.”

On the other hand, the French Revolution, which occurred shortly thereafter, was anchored in the negation of the divine. So much so, that the French changed the seven-day week to 10 days, to distill the notion that God created the world.

Just as today’s America is a byproduct of the American Revolution, to a large extent today’s Europe is a byproduct of the French Revolution.

This leads to the emerging global philosophical divide of the 21st century: Americanism vs Europeanism, and awakens the old biblical debate between monotheism and paganism. Europe is back to universalism, to Greece, to the origins of the 2,300-year-old European-Israeli conflict – the world’s oldest feud.

Zionism as disrupter of the European-Israeli conflict

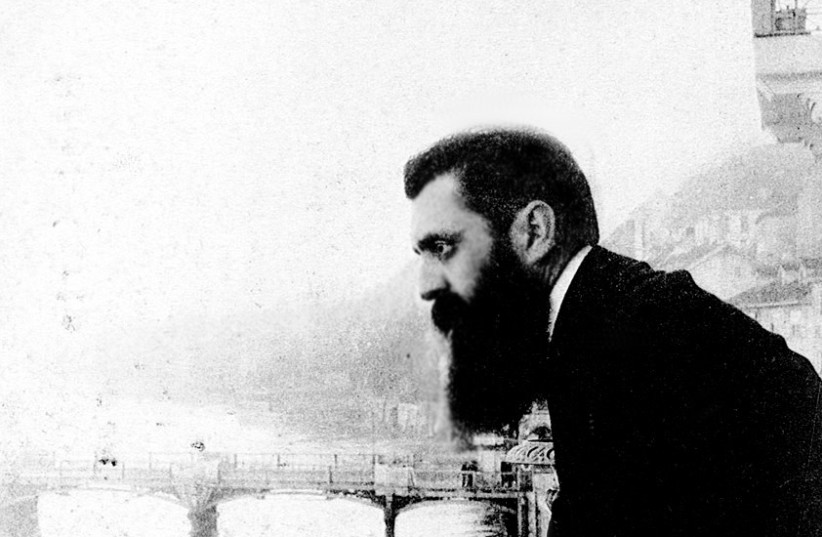

When Theodor Herzl launched Zionism, he disrupted the European-Israeli conflict. Next week, on February 14, will mark the 127th anniversary of the publication of Herzl’s Jewish State, which carried a message similar to that of Moses: We are ascending back to the Promised Land.

Jews in Herzl’s circles treated his book with skepticism and ridicule, leading to weeks of frustration. But then on March 11, an unexpected visitor showed up at Herzl’s doorstep – the English Reverend William Hechler, who announced to Herzl: “We have prepared the ground for you.”

Indeed, many of Herzl’s early supporters were Christians. In the following years, much of the outside world became advocates of Zionism, including the Arab leadership of the Middle East. Just like the outside-to-inside process that occurred during biblical times, this helped push Jews into Zionism and accept Herzl’s message: “We are coming home.”

Today, in the 2020s, the transformation that Herzl seeded is coming to fruition. Zionism is becoming the anchor of Judaism (Judaism 3.0). This is clear to many in America, Europe, Africa, Asia and the Middle East. With that, the ground is prepared for Jews themselves to recognize that we are in Judaism 3.0. The Jews came home to Zion; now so has Judaism. ■

The writer is the author of Judaism 3.0: Judaism’s Transformation to Zionism (Judaism-Zionism.com).

Moses and Zipporah’s ‘Tikkun’?

Was Jethro, Moses’ father-in-law and priest of Midian, late to recognize God? Midian is not mentioned in the Song of the Sea, unlike other nations who were in fear. Only after Jethro hears a firsthand account from Moses, he concedes: “Now I know that the Lord is greater than all gods״

After all, Moses did not divulge to Jethro his revelation at the burning bush, nor the context of his departure to Egypt.

Did Jethro view “Moses’s escape” from Midian in a similar way that Laban viewed “Jacob’s escape” from Haran a few centuries earlier? While operationally, Jacob “defected” clandestinely, Moses “defected” openly, claiming he would like to see if his brothers in Egypt are still alive.

Did Moses apply the lessons of his great-grandfather Jacob in crafting a cleaner escape? And Did Zipporah apply the lesson of her step-great-grandmother-in-law Rachel? Instead of protecting the idols of yesterday as Rachel did, Zipporah protected the future of Judaism, by circumcising their son and saving Moses.