In recent decades, Jewish feminist scholars have been writing on a wide variety of topics, such as commentaries on the Torah, modern feminist theologies, scholarly books in Jewish studies and much more. One of the most groundbreaking and comprehensive compilations of essays by Jewish feminist scholars is the The Torah: A Women’s Commentary, published by Women of Reform Judaism and the Central Conference of American Rabbis (2008).

Following in this path is a new book by Rabbi Marla Feldman, a Reform rabbi who has been studying and teaching midrash ever since she was a college student. It is titled Biblical Women Speak: Hearing Their Voices through New and Ancient Midrash.

In rabbinical school, particularly under the guidance of Rabbi Professor Norman Cohen, she continued to explore how classical midrash treats a wide variety of biblical characters, particularly the women of the Bible. As time progressed, she not only continued to study and teach midrash but sought to give voice to women’s experiences and perspectives through her own creative writing of contemporary midrash. This book is a great example of this.

Rabbi Feldman is an exponent of modern midrash. She explains:

The role of contemporary midrash about biblical women is particularly important: to discover the women whose names are missing from our texts, to amplify the voices of unnamed and named women, and to reconsider and reimagine what additional and/or alternative meanings these texts might hold for us today when filtered through the lens of women’s experiences.

Rabbi Feldman has become an expert on midrash. In an appendix to the book, she presents a very useful overview of midrash, where she explains carefully to the reader all the various forms of midrash that have developed over the centuries. In addition, she presents a very clear definition of midrash:

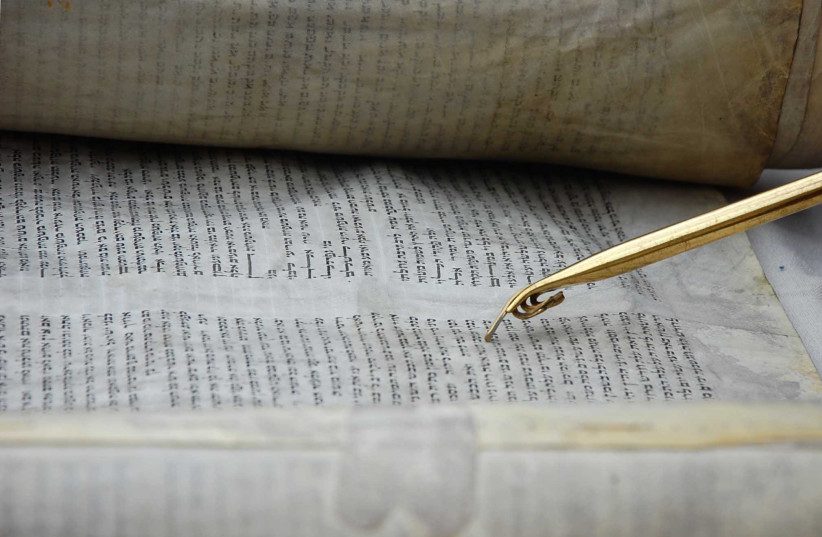

The word “midrash” is derived from the Hebrew root d-r-sh, meaning “to seek.” As noted in the introduction, historically midrash developed as the rabbis plumbed the text for knowledge about its deeper meaning and for direction in how to guide their communities in their own days.

For Rabbi Feldman, midrash is not just a historical process. Rather, as she says in the appendix: it continues as a living art form today, just as it has throughout the ages; and she is one of those rabbis who continue to explicate ancient texts for contemporary readers.

Let me give you some examples.

The story of Keturah, Abraham’s second wife, is not very well known because it only takes up five verses in the Torah (Genesis 25:1-6). According to the text, she bore Abraham six sons, whose names most of us have never heard of. They had many descendants, but Abraham willed all that he owned to Isaac; but to his sons by concubines, he gave gifts while he was still living, and he sent them away from his son Isaac, eastward, to the land of the East.

Based on these verses, Rabbi Feldman writes a brilliant and creative modern midrash, which she calls “Keturah, the Great Mother of Many Generations,” which concludes with the following statement:

Not long after we separated, I heard that my husband had died. He was 175 years old. Thirty-five of those years had been spent with me, but no one thought to tell me! I only learned about it from a passing caravan.

Isaac buried his father alongside his mother, Sarah, Abraham’s first wife. Even Hagar’s son, Ishmael, joined in honoring their father. But neither I , nor our sons, nor our many grandchildren living in the East were acknowledged. We were denied the opportunity to mourn for our beloved Abraham, even to place dirt on his grave. I deserved more than that.

Once severed from my union with Abraham, the sweet, wise Keturah was lost forever. And so, I, The Great Mother of Many Generations, became but a footnote in history.

I found this passage very moving, since to be honest, I have never thought much about Keturah. Indeed, she is like a footnote to the stories of Abraham and the patriarchs and the matriarchs in Genesis. The author’s focus on her motherhood, and how meaningful this could have been in her life, is fascinating. It is also a story of alienation, since all of her children leave her, and she, like Hagar, is left alone in the world.

Another great example is a story concerning Miriam, a biblical character who is more well known, especially for her singing and dancing after the Jews emerge from the Red Sea alive and well. In a very strange passage in the book of Numbers (chapter 12, verses1-16), we read about how Miriam suddenly came down with leprosy after challenging her brother Moses, with her brother Aaron, because he married a Kushite woman! Not only that, but she was exiled from the camp of the Israelites for seven days. Only when she returned did the Israelites continue their journey in the desert.

Rabbi Feldman’s modern midrash about Miriam’s exile, which she calls “Miriam’s Fringes,” is powerful and poignant, as you can see from the following excerpt:

Eventually my eyes opened to the dark. Or, maybe, my focus changes, and this was the miracle after all. Indeed, I saw that I was not alone in this dark and terrible exile. With me with the other marginal people, the malcontents, the rejects, the forgotten, the holy.

At first, I merely observed the others, the ghostlike shadows that ringed the fringes, scarcely visible as they skirted in and out of the light. In my fascination with them, I forgot about my own pain. Here were people like me: damaged, wounded souls, broken bodies clinging to a life where each pain-filled breath was an act of courage. Their images remain imprinted on my spirit.

After my week in exile, I returned to the main camp, and then my people just got up and moved on, as if nothing had changed. No one asked what had happened during those seven days I dwelled at the edge of the camp. Had they asked, I could have taught them something about pain and death and something about life. I learned more about love, charity, and what is truly important in life in my exile that I had from all of God’s and Moses’ teachings. I lost some heroes, but others have replaced them. How ironic that my curse became a blessing. Living among the fringes, I discovered courage and hope; in adversity, I found faith.

Wow! What a beautiful modern midrash, so creative and meaningful. For me, it filled in so much of what was missing in the text, so much of what might have been going through Miriam’s mind in this difficult and overlooked section of the Book of Numbers. This was followed by lots of classic midrashim as to why Miriam’s punishment was so severe, and why only Miriam was punished and not Aaron, who also criticized Moses. In addition, there is Rabbi Feldman’s own commentary in which she suggests that this can be an opportunity for us to focus on people on the fringes of our communities, people who suffer from illness and addiction or struggle to survive poverty, or live as social outcasts, or are elderly, vulnerable and alone. This kind of contemporary commentary makes this book relevant for all of us today.

Who is this book for?

According to the author, it is for rabbis and educators teaching courses about midrash or about particular biblical characters and stories. Also, the author’s commentary provides insights for those people seeking a deeper, more personal connection to the text, and hopefully it will empower readers to explore their own modern interpretations of the texts. This book is, however, not just for rabbis and educators. It is for laypersons as well. It can be meaningful to everyone because it is very personal and contemporary. It offers us an opportunity to put ourselves into the text and to see some biblical narratives via the contexts of our own lives.

In my view, this is an inspirational book that speaks to us of the issues of our times – of the critical problems that we all face in our personal and collective lives – through Jewish classical, modern and feminist lenses. I enjoyed it thoroughly and learned a great deal about many biblical women, some of whom I knew nothing about, and others, like Miriam, whom I knew from only one perspective (as a happy person, dancing with her timbrel after the escape from Egypt at the Sea of Reeds). This book is a masterpiece of scholarship, creativity, and exquisite writing, and I recommend it highly. ■

- Biblical Women Speak: Hearing Their Voices through New and Ancient Midrash

- Rabbi Marla J. Feldman

- Jewish Publication Society and the University of Nebraska Press, 2023

- 264 pages; $26.45