Preparations for the soldiers’ Seders in Jerusalem in 1948 were under the jurisdiction of chief chaplain Shlomo Goren. In various locales in the city such as Ramat Rachel and Camp Schneller, the Seders were so packed that the participants had to stand. To ensure that the essentials were covered, Goren prepared an abridged version of the Haggadah.

In Goren’s book With Might and Strength, he writes, “The city had been under siege for months. Supplies short, rations at starvation levels. No wine, no matzah (this will be explained), no eggs, nothing to make. A token Seder. No way for supplies to reach Jerusalem.”

Though no description how it reached Jerusalem was proffered, Goren discovered 90 kilos of matzah in the city. The military governor of Jerusalem decided the matzah was for the citizens.

Goren was aghast; he argued with the governor because soldiers would be forced to eat chametz. “This is the first Jewish army in Jerusalem in 2,000 years – and they should eat chametz?”

“This is the first Jewish army in Jerusalem in 2,000 years – and they should eat chametz?”

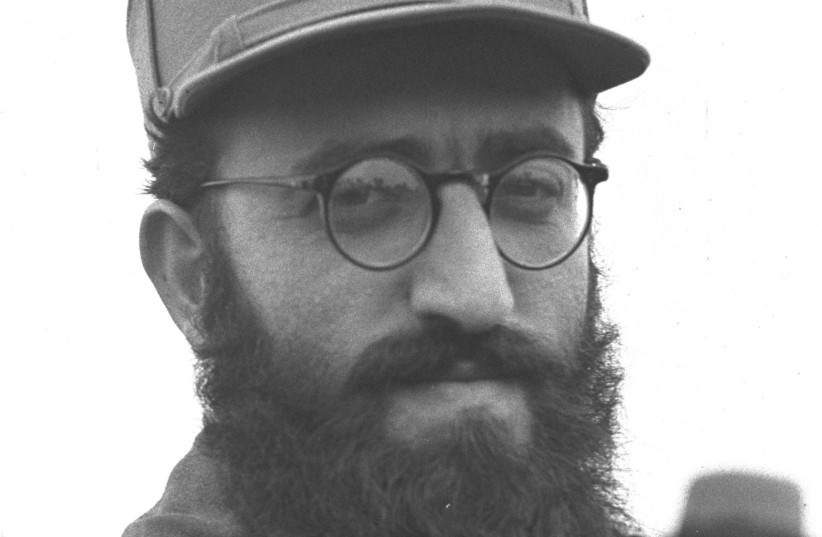

Shlomo Goren

Goren was an individual who could not be deterred. Late one night in the week before Passover, he arranged for a truck and soldiers to accompany him, since he knew where the warehouse for provisions was in Jerusalem. He and the soldiers broke in, as there were no guards. They discovered the matzah, although it is not clear how many kilograms they put in the truck. The next morning, he spoke to the commander of the Jerusalem forces. “We have the matzah. I am requisitioning the amount I now possess. These Jerusalem soldiers will have a kosher Seder.”

The chief chaplain’s speech to the soldiers is found in his book. “I am sure you all know that it won’t be possible for you all to stand at a Seder table and celebrate Pesach the way you are used to doing in your homes.” Goren stressed how this Seder would be celebrated. “At least you will be able to mark this one night and observe the mitzvot, to eat some matzah, have some lettuce and drink a cup of wine – let’s have a Seder.” They also received a minimal amount of food to eat.

When the largest Seder got underway in Jerusalem, Goren announced that a special Elijah would be arriving, so the cup was filled for the special guest. To everyone’s surprise, David Ben-Gurion, a symbolic Elijah, arrived, having been flown from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem in a Piper Cub [a two-seat monoplane].

The soldiers were overwhelmed – the leader of their country, soon to be the nation of the Jewish people, had not forgotten them. In a little-known photo found at the Central Zionist Archives, the joy on their faces was clear for all to see as they surrounded Ben-Gurion, smiling away.

Chief chaplain Goren recalled a portion of Ben-Gurion’s talk.

“Tonight, this is the first time in the 2,000 years of exile that the Jewish people are celebrating the festival of freedom and redemption as a free people back in its own land.” Then he emphasized, “The Seder concludes with the hopeful words ‘Next year in Jerusalem.’ You men are in Jerusalem fighting to liberate it and fulfill that destiny. Do not yield but hold on to Jerusalem tenaciously.”

Ben-Gurion spoke a bit longer then expected, with tears in his eyes, until it was time to return to his headquarters in Tel Aviv.

Dr. D. Thomas Lancaster, pastor of the Immanuel Beth Messianic Synagogue in Hudson, Wisconsin, described Ben Gurion’s unusual exit from the Seder. “The soldiers were so packed into the hall it was impossible for Ben-Gurion to make his way through the crowd to reach the exit.” Just like a miracle, “the soldiers picked him up and passed him over their heads, from one man to another so that he could exit the building and fly back to Tel Aviv.”

CAPTURING THE impact of the siege of Jerusalem in 1948, The New York Times wrote: “The 106,000 Jewish inhabitants face starvation. Bread is rationed to a quarter of a loaf per person daily and there is little meat, poultry, fish, milk, butter, eggs or vegetables for the ordinary people. Even children are going hungry.”

Things were better in Tel Aviv

Despite the proximity of Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, the food situation was infinitely better there. Ration card holders could get three kilos of potatoes, some chicken, and exchange sugar for matzah, which was also distributed free to the poor 10 days before Passover. Advertisements in Hebrew and English papers listed products which had been certified kosher for Passover, and Seder hospitality was advertised for those who needed it.

In 1988, one of the few books in English, Letters from Jerusalem 1947-1948, about Jerusalem in 1947 and 1948 appeared. It was written by American olah (immigrant) Zipporah Porath.

The Association of Americans and Canadians in Israel published the work on the 40th anniversary of Israel’s creation. The book went through three editions, is on Kindle, and was translated into Hebrew.

Porath was a Hagana volunteer before becoming a nurse. The letters featured in her book were the ones she sent to her parents. When her mother died in New York, she went for the funeral and found them.

Here is a sample of her singular style – March 23, 1948, she described the food situation: “For three weeks I’ve been waiting for my grocer to save me an egg... well today he did. With utmost tenderness, he wrapped my egg and placed it on top of my parcel. The entire bus ride I protected the egg vigilantly. Then bingo, right in front of the door, I missed a step, and my treasure went flying. Took the remains, added some powdered milk and powdered eggs and scrambled up a delicious dish.”

On April 25, 1948, her boyfriend Yehuda took her to his family’s Seder. They walked from her apartment in Kiryat Moshe through eerily quiet streets. As they walked, they greeted mutual friends, who sang loudly and waved to people on their balconies who were waiting for guests.

The main guests in Jerusalem were the 100 drivers who had braved the constant shooting and shelling to join the pre-Passover convoy to Jerusalem on Shabbat HaGadol, a week earlier. They were separated from their own families this Seder night, but having helped to provide Jerusalemites with food, they were welcomed everywhere.

As they neared Yehuda’s family home, they passed the residence of chief Rabbi Dr. Isaac HaLevi Herzog, the president’s grandfather.

In her letter after the seder held on April 23, which was Shabbat too, Porath wrote: “A thick security guard stood. The night before [chief] Rabbi [Yitzhak Halevi] Herzog had broadcast, over the Hagana radio. He addressed the women and men in the armed forces as makers of history and called upon them to draw courage from the Passover festival while invoking God’s blessing upon them; Go in this your strength and redeem Israel forever.”

It was the first time Porath attended a Sephardi Seder: “The reigning matriarch was a grandmother whose hand everyone kissed after Kiddush. While the Haggadah was recited in Hebrew, the important passages were reread in Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) for her benefit. Whenever the conversation lapsed into Ladino, the children, little chauvanists, were generally upset and demanded that only Hebrew be spoken,” she noted, before going on.

“The herbs were truly bitter, plucked from the fields like greens we now eat with our daily fare. There was mallow, a spinach-like vegetable, which grew prolifically in the open meadows around Jerusalem. Nutritionists had discovered that mallow had highly edible properties, whether raw or cooked, and it soon became a popular dish.”

To Porath, the haroset tasted just like mortar, she said before continuing with a tale about the afikoman:

“The afikoman was placed in a napkin; its ends tied in a knot, and passed to each person at the table, who in turn slung it over a shoulder and held it there to symbolize the way the Jews carried their belongings out of Egypt. When it fell into the hands of one of the children, it miraculously disappeared and was only forfeited against the promise of a book.”

Porath and Yehuda decided to leave before the end of the Seder.

“It was still early when I arrived at home,” she wrote. “I decided to walk over to the home of Professor and Mrs. Louis Guttman (Guttman was a leading statistician at the Hebrew University where he taught) in the HaMekasher neighborhood nearby, where the festivities were still underway.”

Another Seder by a new oleh

NOW ON to another Seder being held on the night of April 23 when we meet another American oleh, Prof. David Macarov. After World War II, he returned to his home in Atlanta, Georgia following a military career during which he was mainly assigned to India. However, a Zionist all his life, Macarov felt compelled to make aliyah (immigrate) with his wife, Frieda, a nurse. They made aliyah in 1947 after David was told that he could use the GI Bill to pay for his studies at the Hebrew University.

Frieda describes their Seder on that April night: “As April dawned, my friend Bea Sirota Renov, by then a mother, spoke to me about the forthcoming Passover.” Renov grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, and was a Zionist enthusiast throughout the 1930s and ‘40s. She was active in the Atlanta Young Judea youth group and at the religious school in the Shearith Israel synagogue, where, coincidentally, my grandfather Rav Tuvia Geffen z’’l was the rabbi at the time. She spoke Yiddish with her parents, and during World War II, as president of Young Judea’s southern region, she organized Hebrew-speaking groups for members.

“Bea informed me that it was best to have the Seder at their place,” Frieda continued. “She explained that a neighbor had introduced her to the mallow plant, which grew wild and taught her what to prepare from it. As a result, her breast milk had risen in quality and Bea herself had gotten stronger since the birth of her daughter. The decision was made – Seder at the Renovs.”

The only problem – little or no food.

“Chief Rabbi Herzog [grandfather of President Isaac Herzog] understood how to help Jerusalem citizens who wanted to observe Passover in the midst of all this turmoil,” David Macarov explained. “Herzog made a psak [halachic decision] – all food, even if it had hametz content, was kosher to eat on Passover.” Whatever matzah chief chaplain Goren had left was available too.

A scientist as well as a noted Torah scholar, the chief rabbi calmed the religious fears of the 100,000 Jews living in Jerusalem.

Macarov told me that around April 10, 1948, there were rumors that a convoy would get through with food supplies before Passover. Seven days before Pesach, the trucks broke through. Macarov’s vivid description of the convoy’s arrival describes the scene:

“Go down to the Strings Bridge today in Jerusalem and imagine hundreds of Jerusalemites, no one counted them, lining Herzl Boulevard, and other crowds sprawled along Jaffa Road down to what was Shaare Zedek hospital all awaiting the convoy,” he said. “The trucks became real as they emerged from the road below into the city. We were all in tears as we viewed what was plastered on every windshield – the biblical words ‘Im eshkahech Yerushalayim...’ – ‘If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither.’

“We ran to the trucks driving in, grabbed the drivers, handed them flowers and embraced them as best we could. The local girls kissed all the drivers. The Yam Suf (Red Sea) into Jerusalem had been split, and the bearers of substance came through safely.”

The Macarovs received eggs, a chicken, matzah (from the looted warehouse) and dried foods, while the Renovs received more of everything because they had a baby.

Bea had stayed in Hadassah hospital for longer than usual after the birth, following an attack on the convoy carrying doctors and nurses to the hospital on Mount Scopus on April 13, 1948. The convoy was ambushed, and over seventy people were killed. In the weeks following, the one road from Hadassah to the city was watched closely to ensure it was secure. So, the Renovs were given the opportunity to stay on following their daughter’s birth.

“I remember Jerusalem governor Dov Yosef, nattily dressed, shaking hands with the drivers and embracing them warmly,” Macarov stressed. “From afar, it seemed to me Rabbi Herzog was blessing those who had gotten through.”

The Seder night fell on Shabbat. There were the two families; four American-born Jerusalemites – David and Frieda Macarov, Jerry and Bea Renov – and the new Sabra Renov baby, all seated under the stairway for protection. They took a deep breath, slowly realizing that they had left the US and were living in Jerusalem.

Macarov, who had a very good memory, recounted almost every detail to me. “Seder is the order we give to life.” (The word seder means “order”). “This Jerusalem Seder is much, much more. It is freedom, it is on our own soil, it is the laughing and crying of a baby born here. Our ancestors were slaves to Pharoah in Egypt, our sisters and brothers were slaves and slaughtered in Europe, but remnants have survived, with God’s help... and are in this special city tonight.”

Jerry Renov added, “We are eating the bread of affliction, the staple of the desert wanderers; but just as they were privileged to enter the land, we are too.”

He then made the blessing “Sheheyanu vekimanu vehigyanu lazman hazeh” (we are alive and blessed to reach this moment).

“The Renovs had their supplies for the Seder at their home and the Macarovs brought something as well, so by pooling we had special fare for the Seder. Two carrots, some matzah, three potatoes, wine and 100 grams of frozen meat.”

Porath, after visiting the Guttmans, dropped in at that Seder as well. She captured their Seder with these words: “What a unique feeling it was to celebrate the festival of freedom, living with the hope that our own homeland would soon be independent. A few days after Israel became a state, Jerry became one of the first pilots in the Israel Air Force. Everyone in Jerusalem soon knew who he was because one of his tasks was to drop the mail into Jerusalem.”

A dramatic Seder at Yemin Moshe

THE MILITARY outpost in Yemin Moshe was the site of a dramatic Seder attended, among others, by an enterprising reporter named Malka Raymist.

Raymist pulled strings, going through a retired American Air Force Jewish chaplain to reach the Hagana headquarters. There, after several phone calls, she got a signed pass to enter Yemin Moshe.

On Friday evening, April 23, at the Public Information Office just off King David Street, she crossed over to a British sentry post, had her pass checked and walked toward the Windmill. At an unmanned roadblock, she shouted; but as no one answered, she slipped under the barbed wire.

Only then did a soldier appear to check her pass and clear her entrance. As they made their way through a trench, they had to duck quickly when shots whizzed by their heads.

Finally, after walking through winding streets and buildings with large gaping holes, she and her escort got to the command post. After quizzing her briefly, the commander welcomed her. Arriving at the Seder, they saw a long table set with a white tablecloth, matzot and flowers. There were many bottles of wine, mostly gifts from Jerusalem inhabitants of the Yemin Moshe neighborhood.

The soldiers began to arrive – Orientals, Germans, Poles and Hungarians. The few remaining Yemin Moshe civilian residents soon appeared, including a patriarchal figure with a long white beard, dressed in a festive robe that contrasted with all the khaki uniforms. The Seder had a flavor of its own, “full of merriment despite the place and time,” according to Raymist. They used a Haggadah illustrated by noted artist Ariea Allweil for the joint military forces. The Haggadah comprised traditional extracts, original illustrations and appropriate Hebrew poems. (A copy of this Passover treasure, from 75 years ago, survived and made its way to the Pitts Library at the Candler School of Theology at Emory University in Atlanta.)

Selections were read from it and the traditional Seder songs resounded. With patriarchal grace, an old Yemin Moshe resident blessed all assembled. The four sons were represented by the soldiers – each one taking his turn.

Between the third and fourth cups of wine, the phone rang. The commander grabbed it and called for silence. As soon as he hung up, he announced: “Twenty men – outside with me.” Grabbing their rifles, they left quickly. Soon the firing began in earnest and then slowly subsided. One by one the soldiers returned, and as they sat down, another bowl of hot soup was brought out to each one.

After everyone had eaten, the commander made a speech, as unforgettable today as when it was then. “We now are celebrating our liberation from the Egyptian yoke. But at the same time, we are fighting to liberate ourselves and our country from other yokes. The odds are against us,” he stressed. “Have no illusions. The worst is yet to come. When Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt and saw what rotten human material he had on his hands, he decided to get rid of it by remaining with them for 40 years in the desert and letting them die out.

“However,” he continued, echoing the Passover message heard throughout the country that year, “Moses had time. We have no time – only a few weeks, and we must do it now. Be prepared for the worst. Be prepared to give everything. We are fighting for a better future. We are fighting the final battle to free ourselves forever from all yokes. We are fighting for a Jewish state.”