Avi Yefet rolled out the brown dough on a small table as he prepared it for baking in the Old City of Jerusalem.

For more stories from The Media Line go to themedialine.org

The unleavened bread – made up of flour, coriander seeds, canola oil and salt – is a Karaite specialty known as “massah” that is prepared each year for the Passover holiday. It tastes completely different from the traditional matzah most Jews eat during the festival.

For this tiny Jewish community, Passover and the story of the ancient Israelites’ liberation from slavery in Egypt is different from all the others.

What are the Karaites?

Karaite is an ancient Jewish stream that traces its roots all the way back to the revelation at Mount Sinai, when the Israelites are said to have received the Torah, or Hebrew Bible.

“The Karaites are continuing on their path from the Mount Sinai revelation, when the Torah was given to the Children of Israel. We have not changed since then. The Rabbinical Jews, or Pharisees, are those who have changed and added religious laws.”

Avi Yefet

“The Karaites are continuing on their path from the Mount Sinai revelation, when the Torah was given to the Children of Israel,” Yefet, a member of the community, told The Media Line. “We have not changed since then. The Rabbinical Jews, or Pharisees, are those who have changed and added religious laws.”

Unlike mainstream Jews, Karaites reject rabbinical authority and recognize the sanctity only of the 24 books of scriptures that make up the Hebrew Bible. They do not believe that Moses also received an Oral Law, and consider the Talmud or Mishnah, the first major written collection of the Jewish oral law, to be cultural heritage rather than authoritative religious texts.

Karaites have no rabbis, only sages, according to Oshra Gezer, vice-chair of the Universal Karaite Judaism organization, and they follow a different religious calendar than traditional Jews.

“The biggest difference between Karaite and rabbinical Jews is that Karaite Jews place the individual in a position of power; in other words, every person is required to know the Bible, to read it, to learn it, and to interpret it according to his or her understanding.”

Oshra Gezer

“The biggest difference between Karaite and rabbinical Jews is that Karaite Jews place the individual in a position of power; in other words, every person is required to know the Bible, to read it, to learn it, and to interpret it according to his or her understanding,” Gezer told The Media Line during a recent visit to the group’s heritage center in Jerusalem’s Old City.

“Whatever the individual understands, that is what they should do and there is no relying on someone else” like a rabbi, Gezer added. “There is personal responsibility.”

At the Karaite Heritage Center in Jerusalem, leading members of the community are eager to expose the wider Israeli public to their unique way of life.

One of the center’s highlights is a 13th century synagogue – one of the oldest of its kind in the Old City – which requires visitors to shower the same day before entering. Women who are menstruating are forbidden from going in, based on the biblical concept of niddah, or ritual impurity.

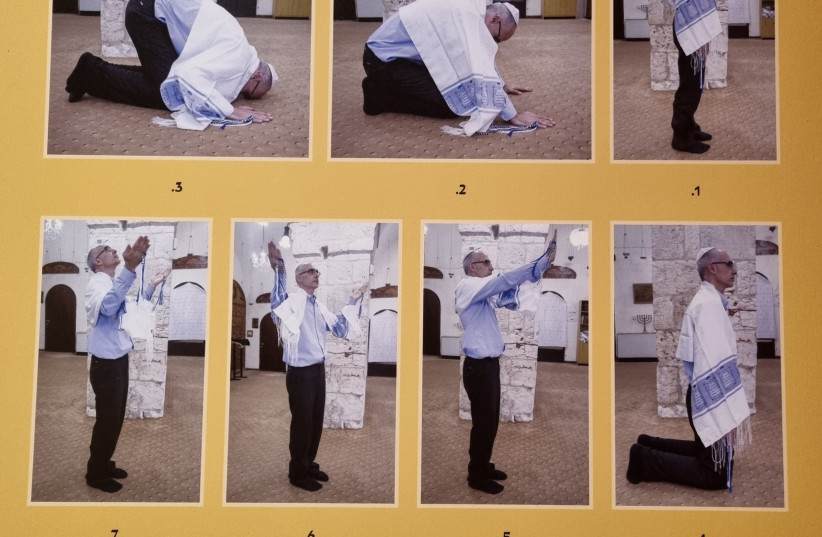

The modest space is carpeted and prayers are held without any seating for the most part, similar to mosques.

“The synagogue is a temple and the Karaites protect its sanctity and purity,” Yefet, the synagogue caretaker, explained. “Visitors must be pure and enter without shoes.”

During the festival of Passover, Jews gather to tell and retell the story of Passover to countless generations by reading from the Haggadah, a text that recounts the Exodus from Egypt.

As in so many other instances, the Karaite Haggadah is different.

“The Passover Seder [or ritual feast] is conducted differently for Karaites, from the text we read to the way it is carried out,” Gezer explained. “We are required to sit around the table and tell our children the story of the Exodus from Egypt. We tell it to our children as it is told in the Book of Exodus. It’s much shorter than the traditional Haggadah. Ours is also written in Hebrew, not Aramaic.”

“We are required to sit around the table and tell our children the story of the Exodus from Egypt. We tell it to our children as it is told in the Book of Exodus. It’s much shorter than the traditional Haggadah. Ours is also written in Hebrew, not Aramaic.”

Oshra Gezer

For thousands of years, the Karaites have held on to their belief in the sanctity of the written word, as expressed in the Hebrew Bible.

There are currently 50,000 Karaites worldwide, with the vast majority residing in Israel. Although the community is small, Gezer says, interest in its practices and beliefs has grown in recent years thanks to its egalitarian treatment of women and its rejections of rabbinical oversight.

For instance, Karaites are the only stream of Judaism in Israel that can legally get married outside of the rabbinate. They also conduct their own divorces, circumcisions and burials.

“Karaite Jews are the only Jewish group that has received legal approval to autonomously carry out their practices,” Gezer said. “I’m not sure that the numbers are growing, however there has been a renewed interest in Karaites recently due to the [political] situation we now find ourselves in in the country.”

“Karaites advocate for and believe in gender equality,” she continued. “Karaite women have equal rights and can carry out any religious role that Karaite men can: she can be a cantor, a circumciser, a kosher butcher or lead a community.”