When once again we sit around our Seder tables and read the Haggadah, we will relive the foundation myth of the Jewish people.

The story of our ancestors’ enslavement in Egypt and their liberation in the Exodus serves as a social and psychological archetype in the life and mind of all people who have been victimized or oppressed.

For Jews and Christians in particular, the Exodus story is an event of “biblical proportions.” It is the story which is most mentioned in the Bible, in our liturgy, and in the rabbinic literature.

In Mishna Pesahim we are reminded: “In every generation man is bound to regard himself as though he personally had gone forth from Egypt.”

And in our prayer books we read: “From Egypt you redeemed us, O Lord our God, and from the house of bondage you delivered us.”

As I was reminded over and again in my seminary studies, “The defining metaphor of the Jewish people is the Exodus from Egypt.”

In this perspective, it is likewise a metaphor for all people who have experienced oppression and sought liberation.

Michael Walzer, the distinguished professor emeritus of social science at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Princeton University, wrote in the preface to his book Exodus and Revolution: “The escape from bondage, the wilderness journey, the Sinai covenant, the promised land: all these, loom large in the literature of revolution.”

In fact, the leaders of the American Revolution – which included Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin – had proposed that the Great Seal of the United States depict the Exodus from Egypt. Although the proposal was not approved, in their minds the Exodus story exemplified the American struggle for independence.

In African-American culture, the story of Egyptian slavery was popularly taken as a metaphor of their own slavery and the injustice which they experienced. In turn, the Exodus served as a symbol of their aspiration for liberation.

In contemporary American terms of reference, the Exodus saga has served as a model for social change. And there is, as well, a parallel message with individual meaning. As noted in the rabbinic description of the Haggadah narrative: “The story begins with a description of our degradation but ends in praise.”

Depending on one’s personal or shared experience, one may be struggling with the psychic or physical reality of fear and oppression. In such circumstances, the metaphor of liberation can inspire one’s conviction to reject defeatism and to find a way to new life.

Today in Israeli society, we can easily identify with the dramatic metaphors of liberation and oppression. Our society has been deeply seared by horrible acts of inhumanity, accompanied by the firing of guns and the falling of rockets and bombs. Many of our own making. But not these alone. We have also been overwhelmed by fear, by anger, by rage and anxiety.

In response to the oppressive reality of our lives, many of our people have reached out to one another with prayers of hope, shouts of anger, and chants of social revolution.

The Exodus metaphor in many ways defines the reality of Jewish life over generations. But it is the narrative of our history which informs and explains our reality.

As a collective, we have experienced slavery and racism. We have been victimized, persecuted, and murdered for being different. But we, too, have victimized and persecuted and killed others for being different and dismissive of our narrative. And too, we have sought retribution for the suffering and murder of thousands of our people, including many of our soldiers.

These experiences, collective and individual, are embedded in our memory and are integral elements of what Freud called our psyche and what Jung defined as our collective unconscious.

Today, one does not need a rabbi or a psychologist to explain the evil and injustice of war and the devastation it brings. We see it around us; we read of it in our papers; we cry when we watch televised news reports from the field of battle or of funerals for our soldiers. And then there are the painful reports and photographs of masses of hungry children and innocent civilians.

The history of conflict in which Jews have played a significant role is obviously not limited to the wars in which the State of Israel has been involved. From time immemorial, the Jewish people have been targeted and/or tendentially involved in the religious wars and crusades of other religious groups. And when the entire world engaged in wars of conquest, often defined by racist and irredentist policies of colonialism and military expansionism, the Jewish people – regardless of their patriotism and support – suffered disproportionately.

When reading our Haggadah this Passover, we cannot avoid reflecting on our collective historical and contemporary experience. The pain is searing. Our mind’s eye is riveted on pictures, old and new, of Jewish victims of terror and annihilation. But lest we forget, we have no right to laud our experience over that of others.

Excessive recrimination and acts of collective punishment are morally unacceptable and ethically wrong. These, too, are principles which are based on Jewish experience.

To return to the Exodus metaphor, it is of historical note, framed by our national myth, that following our escape from Egypt, while wandering in the desert, our ancestors engaged in contentious struggles, even at Sinai.

It was there, according to our literature, that we received the gift of Torah, our symbolic “tree of life.” And, however we describe the event – “metaphorical,” “mythical,” or “actual” – the Torah has come to serve us as a symbol of our covenant of faith and belief. It gives expression to our code of morality and justice.

How, then, do we understand our role as Jews who have reached the Promised Land?

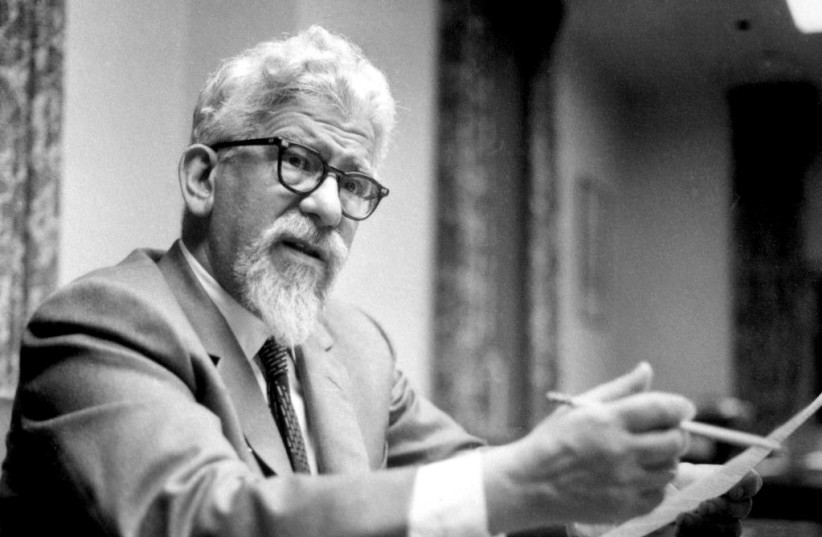

In fact, the answer to this question is the same wherever Jews live. It is to be found in the wisdom of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, perhaps the greatest prophetic voice of our era. He said, “Our task is to find an answer to a crucial question: What is our generation’s obligation? What is the task?”

Heschel’s answer, with a nod to the human history of war and Holocaust: “Our task is not to forget, [and] never to be indifferent to other people’s suffering.”

He also said, “Racism is man’s gravest threat to man – the maximum of hatred for a minimum of reason.”

In his lifetime, Heschel was speaking about the Jewish victims of the Nazis and of the racial minorities in America and the Vietnamese people in their war-torn land.

I believe that if Heschel were alive today, he would apply the same principles to our relationship with the Palestinians – those who are Israelis and those who live in the West Bank and in Gaza.

“You shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Lev. 19:33).

May we be blessed to see the time, perhaps by next Passover, when Jerusalem will be the functional center for two peoples living in peace and justice.

Next year in Jerusalem! ■

Stanley Ringler is an Israeli Reform rabbi. His book The Arc of Our History, acclaimed as ‘a powerful account of major events in Jewish and world history,’ is available on Amazon.