The Yizkor prayer, recited primarily among Ashkenazi Jews, asks God to remember our loved ones who have died. The prayer is recited four times during the year: On Yom Kippur and on the Shalosh Regalim, the three pilgrimage holidays, Passover, Sukkot and Shavuot. As we approach Shmini Atzeret, the conclusion of Sukkot on which we recite Yizkor, it is worth asking why those times were chosen.

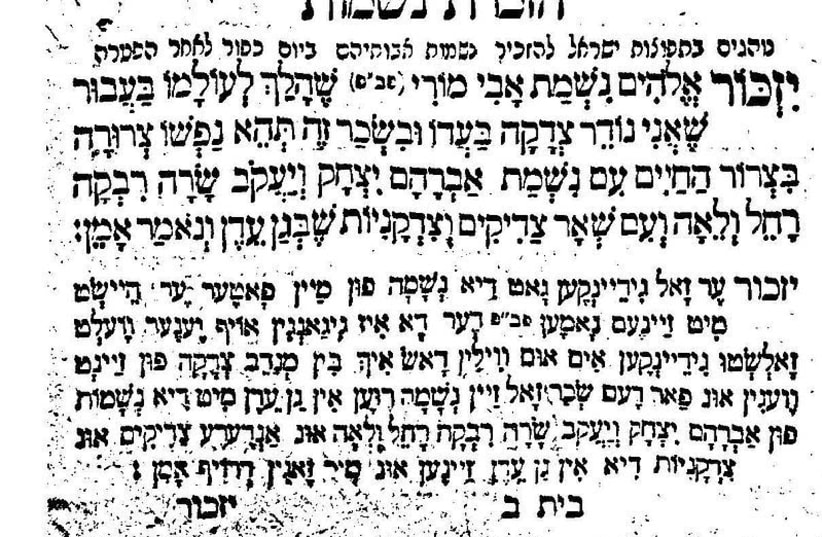

The conventional explanation is that originally Yizkor was instituted in medieval times to provide an opportunity for people to donate in memory of those who died. The prayer does speak of giving tzedaka in their memory, as a way of continuing the values for which they lived. As the Torah reading for the festivals (the 28th chapter of Numbers) also mentions donations, Yizkor expanded to those times.

Yet we can search for a deeper reason as well. Yom Kippur is a solemn day, but not a sad one. At the end of the day we feel cleansed of our sins and the new year has begun. The essence of the day is renewal.

ON SHAVUOT, we celebrate the giving of the Torah. Once again, the Torah represented the beginning of the spiritual journey of the Jewish people. After slavery came the renewal of purpose and possibility.

Passover is the spring holiday. Spring is nature’s tribute to renewal. Where once the empty, withered branch stood, now is the flourishing of green.

Finally, the holiday of Shmini Atzeret leads into Simhat Torah, when we begin the reading of the Torah anew. Once again, the end and beginning, the renewal, is a central theme of the holiday.

This says something profound about the Jewish attitude toward death. Rabbi Hertz in his commentary mentions that when we do kriah, the tearing of one’s clothes in response to death, that the ritual must be done standing. For this is how we meet the reality of death in this world – with the courage to carry on. Indeed, it is precisely the lives of those who have died that are to provide us with our central lessons.

The sense of renewal surrounding death in Judaism refers both to those who survive and to the one who has died. There is the renewal of life among those who mourn: the seudat ha’avarah, meal of transition, follows the funeral. Even one who is not hungry is encouraged to eat. Life must be reinvigorated for that is the task of the living.

Renewal is not confined to the living, however. There is also a subtle message in the word ‘yizkor,’ which is in the future tense. God will remember because life is renewed in another form. Jewish beliefs about death and afterlife are many and varied. However, one thing they all have in common is that this life is not the end. Human beings have a divine spark in them and whatever form it takes one it leaves this earth, it does not vanish.

Yet Judaism is a tradition tied to the realities of this world and the celebration of this life. The certainty of eternity does not eliminate the pain of loss, which is why Yizkor exists. Shmini Atzeret in particular adds a dimension to Yizkor that is haunting and beautiful. Of all the major holidays, the explanation of Shmini Atzeret seems the most elusive. Essentially, it was an additional, eighth day, of gathering. Our ancestors made a pilgrimage to the Temple planning to be there for the requisite week and the Rabbis imagine God saying, “Don’t leave yet, stay one more day…”

When we lose someone we love, that is the feeling that comes over us. If we only had one more moment, one more day. One more opportunity to talk with them, hold them, turn our faces together to the sun and express our love. Shmini Atzeret reminds us that God “feels” the same way, wishes for our presence after all the holidays just a bit longer. And so we pray that God will gather our loved ones in the Divine embrace while we, brokenhearted and openhearted, remember. And that through this act of memory, fidelity and faith, we will renew ourselves and our world. ■

The writer is Max Webb Senior Rabbi of Sinai Temple in Los Angeles and the author of David the Divided Heart. On Twitter: @rabbiwolpe