A careful reading of Parshat Balak can lead to far-reaching geopolitical implications for our days

Something does not add up in the geopolitical actions of Moab’s King Balak. He seems to be acting in contrast to the Moabian interest.

The arch rival of the Moabians is not the Israelis – it is the Amorites who captured Moab’s land in a brutal war. It is clear that there is no “acceptance” of the loss, as evident 300 years later in the exchange that led to the Israeli-Amon war.

Such lack of acceptance existed in Theodor Herzl’s time. He observed how the sentiment of “Revengism” consumed France. The French refused to accept their loss of Alsace-Lorraine to the Germans in the 1870 war. This French sentiment was the backdrop to the Alfred Dreyfus Affair and to French institutional antisemitism that spanned multiple branches of the French government, military, press and society.

Amon to Moab seems to be what Germany was to France in late 19th century.

And here comes a white night. The Israelis liberated the occupied Moabite territories from Amon. This while stating at the onset that they had no claims to those territories. They were just passing through on the way to Canaan. Moab’s “revengism” was delivered by Israel.

In addition, the Israelis have taken down a possible secondary adversary of Moab: the Rephaites, who used to rule the territory then held by Moab. Og ,the last remaining Rephaite King, likely represents a sense of insecurity for Moab. Some day he might seek to reclaim his old land. Indeed, Otto von Bismarck, the first German chancellor whom Herzl admired, predicted in late 19th century that as soon as France was strong enough, it would initiate a war with Germany to reclaim its lost territory.

The Moabian insecurity relative to the Rephaites is akin to Turkey’s insecurity relative to Russia. Around the same time that France got its revenge at Germany, Turkey got its own prayers answered: Christian Russia was about to get Constantinople (Istanbul) after 460 years of Muslim rule. But the 1915 Constantinople Agreement was never implemented, because a Revolution in Russia occurred. The Bolshevik revolutionaries withdrew from the war (World War I), and forfeited Russia’s claim to Constantinople. But today, a century later, Communist rule is over and Russia has resumed its interest in Christianity. Hence, there is likely a growing latent insecurity in Turkey, just like there was in Germany relative to France, and in Moab relative to the Rephaites.

The two strategic threats to Moab – the Ammonites and Rephaites – were removed by Israel, whose strength enabled it to proceed toward Canaan and leave the area.

So why does Balak act against the Moabian interest, and hire Bilaam to curse and weaken Israel?

Is Balak a Midianite king?

A possible explanation can be found through a careful reading of the text. Balak is described as king to Moab, as opposed to king of Moab, seemingly “assigned” to Moab, and therefore not pursuing the Moabian interest, but that of someone else

This could be due to the outcome of the Amorite war, when the Amorite king took all the land of Moab till Arnon. It is possible that a puppet government was put in place in southern Moab, akin to the 1940s’ Vichy government in France. Or similarly, as discussed in previous articles (see parashaandherzl.com), Midian likely wielded a “sphere of influence” in the region, and Balak could be a Midianite King assigned to Moav – hence referred to as king to Moab.

Moreover, while Balak is described by the biblical narrative as king to Moab, Bilaam, a member of the Midian coalition, describes him as king of Moab, e.g. for Midian, Balak is apparently the king; this while the Moabites themselves do not refer to Balak as King of any sort, and simply refer to him by his name.

Indeed, Balak’s name supports the theory that he was not a Moabite, but rather a “colonialist” or puppet Midianite king. His name, Balak ben-Zipor (son of a bird), is consistent with Midianite names: Zipora (female bird), and Orev (crow). More support is provided later when Israel launched a military operation against Midian. Israel killed the Midianite kings and among them the princes of Sihon. The presence of those Amorite princes in Midian is indicative that those local kings were in Midian’s “sphere of influence.”

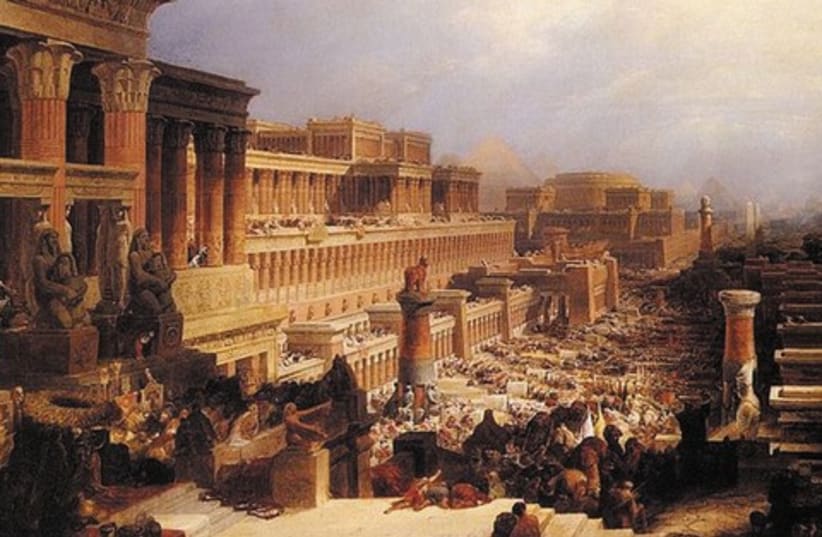

The elimination of Midian’s influence paved the way for others to impact the region’s geopolitical realities: Aram, Assariya, Babylon and for the last 2,300 years, Europe (starting with the Greeks and Romans).

Indeed, shortly after France got its revenge at Germany, it was also set to avenge the British, who the French felt robbed them from getting a piece of the Middle East (the Sykes–Picot Agreement). The British were awarded a mandate for Palestine by the League of Nations, core to which was the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine (this was long before the term was used for the local Arabs’ national movement). In 1920, a utopian Middle East existed: an Arab Kingdom of Syria – led by pro-Zionist king Faisal, who strongly supported the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine – living peacefully next to such Jewish homeland in-the-making, under the caretaker governance of the British.

But the peaceful Middle East of 1920 was ruined by France (France has been a serial destabilizer of peace in the Middle-East from the Crusades through Napoleon). The French invaded Syria, kicked out the pro-Zionist Arab king, and plunged the Middle East into a century of turmoil: Artificial countries were formed to compensate the Arabs for the French aggression (Iraq and Jordan), and Arabs in Palestine were eventually forced by the outside to develop a new national identity as Palestinians, as opposed to as Syrians.

Luckily for Moab, Bilaam resigned and the anti-Israel actions of Balak failed. The subsequent Israeli military operation in Midian liberated Moab from Midian’s suffocating hug, and Moab prospered for centuries to come.

Today, Arabs in Palestine are still suffering from the suffocating European hug. Europe continues to promote its own interest at the expense of Palestinians, reflected for example in Europe’s relentless effort to sabotage Palestinian employment and mentorship in Jewish-owned businesses, in creating debilitating dependencies and in funding organizations that perpetuate Palestinian victimhood.

Indeed, our evolving geopolitical realities today help us understand better the stories of the Bible. But reciprocally, it also helps us apply biblical geopolitical lessons to our own circumstances and to use them to promote peace.

The writer is the author of the upcoming book Judaism 3.0 – Judaism’s transformation to Zionism. For details: Judaism-Zionism.com. For his geopolitical articles: EuropeAndJerusalem.com.