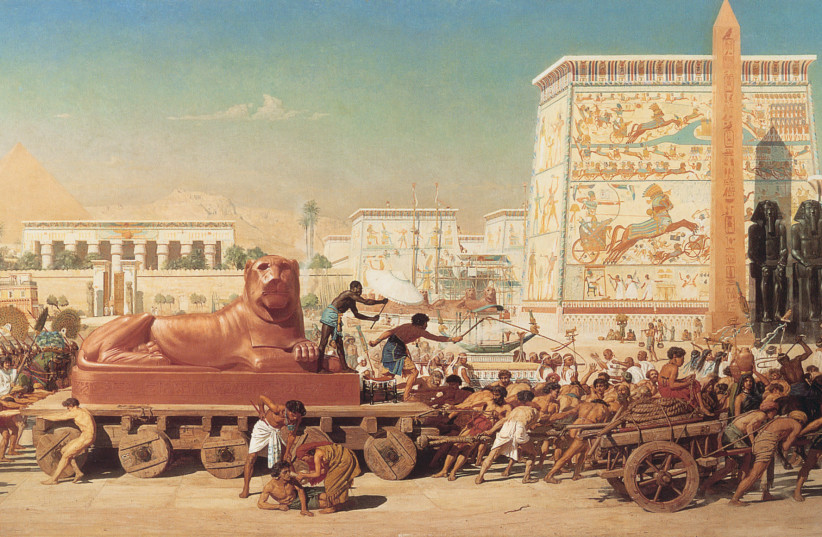

Once a superpower capable of supporting the entire planet, Egypt was reduced to rubble, under the crushing weight of 10 supernatural disasters.

Moses’s fame quickly spread, as popular opinion swung against Pharaoh’s inflexible policies.

Despite all this drama, the Jews remained muted and sidelined. Burdened by bondage and stymied by suffering, the Jews were passive spectators waiting on the sidelines, as the redemption gathered momentum.

What could possibly awaken these listless slaves and empower them toward their own liberation?

The opening verses of parashat Bo provide the solution: we were to become storytellers to our children and grandchildren. Somehow, the expectation of storytelling awakened their depressed spirit and galvanized them into redemptive mode. Ultimately, the slaves rallied, defying the Egyptians masters, and marched out of Egypt with triumphant arms stretched to heaven. Narrating our story of slavery and redemption fired up their vision and roused their inspiration. Telling a story is a mentality, not just an experience.

Imaginations are transformed when people sense that their personal lives are part of a larger story. Generally, stories are told about epic events with consequential outcomes; stories rarely speak of common or humdrum moments of daily life. By viewing our lives as part of a larger story, we realize the import of our behavior and the magnitude of our decisions. Living life as part of a story lends consequence to otherwise bare experiences.

Additionally, stories contain a narrative flow of chapters. A snapshot provides an isolated and unconnected image, whereas a story consists of a current of different streams. Each chapter in a story is shaped by previous chapters and determines the arc of future chapters. Framing our lives as part of a larger story connects our individual lives to the heroes of the past and to unknown descendants of our future.

Retelling this dramatic story of slavery and redemption transformed the hollow lives of slaves into the historic lives of free men. Slaves exist in perpetual survival mode, barren of any larger meaning. Telling their story to future generations conferred meaning and historical sweep to the lives of newly minted fathers and grandfathers. Slaves cannot imagine family and future, but free men are able to ponder the future and their heritage.

The idea that their lives were, in fact, a story liberated their crushed spirits, unleashed their shuttered imaginations, and instigated the role of the Jewish slaves in the redemption from Egypt. Hearing that they would bear grandchildren provided a horizon of hope that something grand loomed beyond the pyramids and beyond the hot sands of the desert.

EACH GENERATION has its distinctive challenges. A hundred years ago, Jewish immigrants arriving to the West struggled to observe Shabbat. Subsequent generations battled against secularizing trends which weakened religious observance and Jewish identity. Thankfully, over the past half-century, Jews across the world have crafted stable and robust communities, many of which have witnessed impressive religious revivals. Perhaps the challenge for this generation of Jews – particularly those who reside outside the land of Israel – is to more deeply identify with the larger story of Jewish history.

In past generations, persecution of Jews created an immediate “alliance” with past generations. Hatred and discrimination felt eerily similar to the past chapters of the Jewish story. Thankfully, much of the world has turned friendlier toward Jews, making it difficult for many Jews to envision themselves as part of a larger story.

Furthermore, Jews have now become part of many alternate stories. Jews have become authors of important modern stories: the evolution of democracy, the advance of science, the development of modern culture, the crusade for social justice, and many other stories. All of these stories should be viewed as part of the larger Jewish story, but often they are read as separate narratives, unrelated to our common Jewish story.

Last year, our generation lost its greatest spokesman of Judaism, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. He reminded Jews that “our” story is also “their” story. For the past 2,000 years our eternal story seemed peripheral to the more prevailing story of humanity at large. The Jewish story appeared to be in hibernation, as the rest of the world continued to author volumes of their respective national narratives. Rabbi Sacks eloquently articulated that the Jewish story was a microcosm of the larger story of humanity. The Jewish odyssey provided vital messages for the larger narrative of humanity. Rabbi Sacks reminded us that our Jewish story, which often feels parochial, is also a universal tale. Being reminded that the Jewish story is a universal narrative has helped many more deeply identify with our story and reclaim weakened Jewish identity.

For 2,000 years, the book of the Jews was sealed. Prophecy ended, and Jews became sidelined as victims of history. With our return to our land and to the center stage of history, the book has been reopened. We are all writing the final chapters of this story. These chapters describe the final frames of history and the struggle of our people to resettle its ancient homeland. This book will be read by our grandchildren and their grandchildren.

Pick up your pen and start writing.

The writer is a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, a hesder yeshiva. He has smicha and a BA in computer science from Yeshiva University as well as a master’s degree in English literature from the City University of New York.