The first part of Emor deals with limitations put on priests who work in the Temple. Seemingly, this topic has no relevance to us today. It’s been 2,000 years since the Temple was destroyed. However, examining these laws can teach us something about Jewish values, which also have implications for current issues.

The limitations placed on the kohanim are primarily regarding impurity and purity. What is impurity? Here it refers to a person exposed to the body of a dead person. This closeness with death, whether it is physical contact or even being under the same roof as a corpse, defines the person as “impure.” The implication of this definition is the prohibition to enter the Temple or come into contact with the sacrifices.

The concept of impurity was meant to maintain a distance between the hard, painful aspects of life and the lofty and sacred aspects of the Temple. An impure person was not limited in his usual life habits, and actually was not even obligated to purify himself unless he wanted to enter the Temple or come in contact with sacrifices.

Incidentally, even today when the Temple is not standing, there is a prohibition of someone who came into contact with a dead person from entering the Temple Mount. Since we have all been in some contact with a corpse (by even being in a hospital that has a morgue), the Chief Rabbinate has determined that all are prohibited from entering the Temple Mount complex.

So, a regular person can become impure by being in contact with a corpse, but what should a kohen do who works in the Temple?

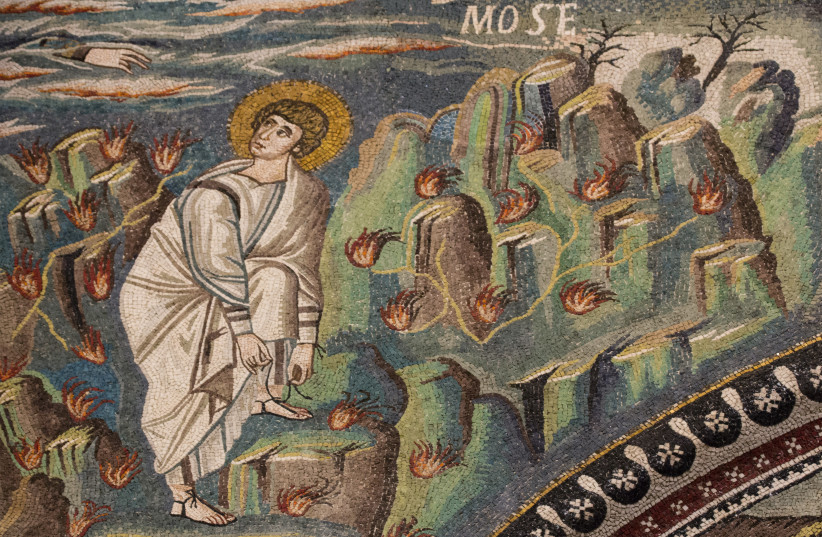

“And the Lord said to Moses: Speak to the kohanim, the sons of Aaron, and say to them: Let none [of you] defile himself for a dead person among his people” (Leviticus 21:1).

Until today, kohanim are commanded to beware of impurity from contact with a dead person. Many kohanim are careful in participating in funerals, visiting cemeteries and being near a dead person. What is the law regarding a kohen whose relative passed away?

The Torah refers to this and details a list of seven relatives for whom the kohen becomes impure: father and mother, son and daughter, unmarried brother and sister, and the kohen’s wife. When one of these dies, the kohen is commanded to leave his shift at the Temple and take care of the burial without consideration of the impurity affecting him. Afterwards, he will undergo a process of purification. But during these difficult moments, the death of the close relative takes precedence.

It is important to understand: The work in the Temple was considered one of the spiritual peaks a human being could attain. The kohen was called upon to do his work with full concentration and complete intent. But the value of family is of even greater importance. There is no space for spiritual peaks without the foundation of proper family ties, which in this case are expressed by taking care of the burial of a relative who passed away.

There is one exception: the high priest. This one person, the one and only exception in the nation, was commanded to be wholly devoted to the work of the Temple. His personal life was set aside.

“And the kohen who is elevated above his brothers… shall not come upon any dead bodies; he shall not defile himself for his father or his mother. He shall not leave the sanctuary, and he will not desecrate the holy things of his God” (Leviticus 21:10-12).

The high priest’s special religious and national role obligated him to focus on his work, even when that means temporarily putting his family aside. But even for this special person there was one case in which he was commanded to leave the Temple and take care of the body of a dead person. This is the case of the “met mitzvah”: an anonymous person who does not have anyone who can take care of his burial. In this case, the high priest himself leaves the Temple and defiles himself to honor this person for the last time.

The order of priorities that the Torah outlines is unequivocal. The greatest religious role of work at the Temple does not defer normal family relations with the singular exception of the high priest, and even then – the honor of an anonymous person defers the spiritual peak of work at the Temple. ■

The writer is rabbi of the Western Wall and Holy Sites.