This Shabbat, we will read the two short Torah portions, Nitzavim and Vayelech. These conclude Moses’ lengthy speech, which has dominated most of the Book of Deuteronomy. They also mark the beginning of the preparations for Moses’ impending departure from this world and his parting from the Children of Israel before their entry into the Land of Israel – after the journey he had led during their 40 years in the desert.

As Moses prepares to bid farewell, he foretells the future exiles and the ultimate ingathering of the exiles, accompanied by spiritual elevation: “…and you will return to the Lord, your God, with all your heart and with all your soul, and you will listen to His voice… then, the Lord, your God, will bring back your exiles, and He will have mercy upon you. He will once again gather you from all the nations... And the Lord, your God, will bring you to the land which your forefathers possessed…” (Deuteronomy 30, 2-5).

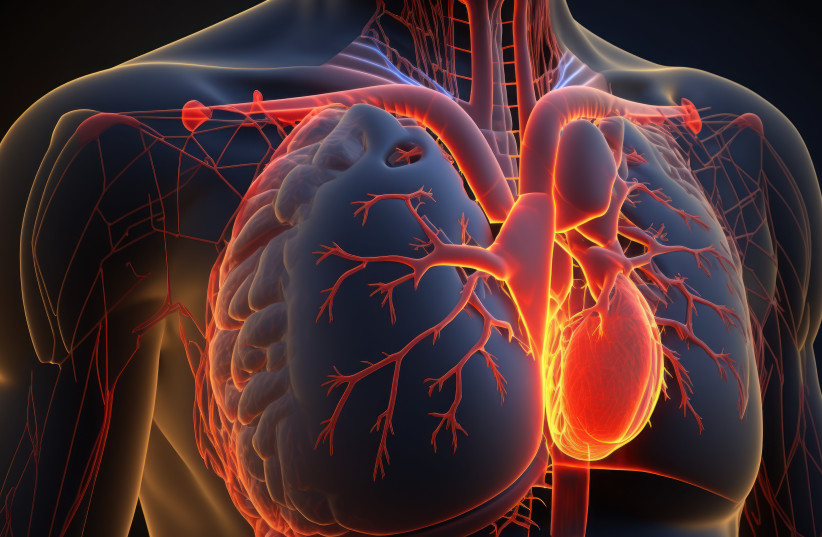

Subsequently, we read about another future spiritual elevation of the Jewish people: “And the Lord, your God, will circumcise your heart and the heart of your offspring, [so that you may] love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul...” (Deuteronomy 30, 6).

Circumcise your heart?

The metaphor of “circumcision” is intriguing in this context. The Torah’s intention is that the Jewish people are not merely expected to fulfill commandments but to ascend to a higher spiritual level characterized by their love for God. However, the Torah does not employ the terms “progression” or “ascension,” or even “transformation,” but rather “circumcision of the heart.” What is the meaning of this metaphor?

In the well-known circumcision ceremony that we perform on an infant boy, eight days after birth, we remove the foreskin to reveal the flesh beneath.

“Circumcision of the heart” conveys the belief that spiritual elevation does not necessitate a total change in a person’s character; rather, it requires the revelation of the inner good concealed within each of us. Purity exists within every individual, and what is needed is merely the removal of the external covering.

This idea is expressed in our daily morning blessings when we say, “My God, the soul which You have placed within me is pure.” These words can be said by anyone, regardless of what he or she did the night before or during the past week. Our actions may blemish the covering, but the purity of the soul remains. We are called upon to recognize that beneath the coverings, there resides a pure soul.

Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, an 18th-century hassidic leader from Ukraine, teaches us that the way to spiritual elevation is not rooted in self-criticism or searching for shortcomings but rather in searching for the good: Even complete sinners can exert effort and find a “good point” within themselves from which they can begin a process of growth and rectification.

The search for the “good point” within ourselves is not just a technique of positive psychology aimed at nurturing the existing good. It is a deep belief in every person, in every situation, that there is no one entirely negative; every person can say every morning, “My God, the soul which You have placed within me is pure.” The nature of a person is such that when the or she illuminates this “good point,” it awakens and influences all aspects of his or her life.

We stand a week before Rosh Hashanah, when God judges all of humanity for the coming year, which begins according to the Hebrew calendar. These are days of soul-searching and personal and communal improvement. However, it does not mean that a person should dwell on self-criticism and despair. On the contrary, we are called upon to focus on the good deeds we have performed, recognizing that beneath the surface, sometimes concealed beneath thick layers, there is a pure soul.

By doing so, we prepare ourselves to stand before God and merit, with His help, a good and sweet year.

The writer is rabbi of the Western Wall and Holy Sites.