The Book of Exodus opens with stories of self-sacrifice that preceded the exodus from Egypt.

Starting with the Hebrew midwives who although commanded by Pharaoh, the ruler of Egypt, to kill all male infants and yet defied his order; through Yocheved, Miriam, and Pharaoh’s daughter, who risked their lives for Moses’ birth and upbringing; all the way to Moses, who grew up in the Egyptian palace and went out to see his enslaved brothers and assist them. This laid the foundation for the redemption – acts of self-sacrifice for the sake of others.

Later in the story, after the exodus from Egypt, when the nation reached the shores of the Red Sea, we encounter another story of self-sacrifice that brought about the awaited redemption. When the people found themselves in a dire situation, with the sea in front of them and the Egyptian army behind, and no apparent way out, Nachshon ben Aminadav was the first to jump into the water. This act led to the miracle of the splitting of the Red Sea, allowing the entire nation to pass through on dry land.

There is a famous saying: “It is easier to take the Jews out of exile than to take the exile out of the Jews.” This was precisely the situation of the people leaving Egypt.

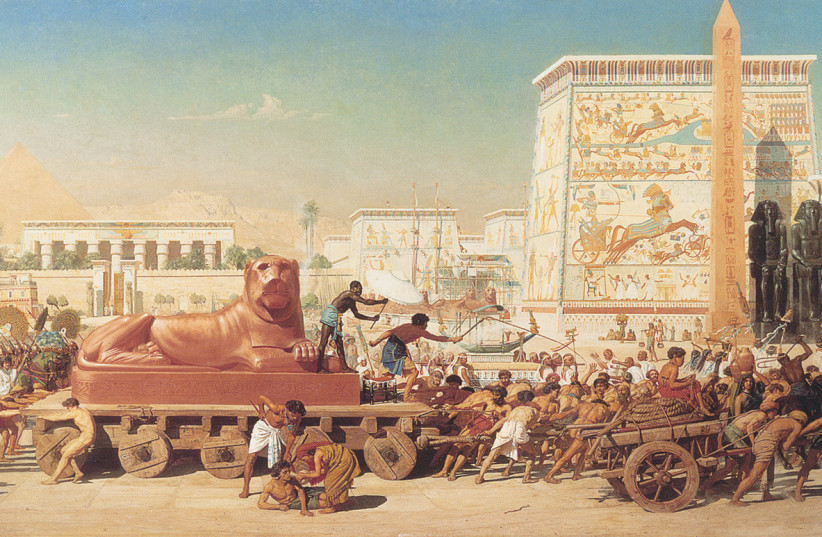

The acts of self-sacrifice that helped free the Jews from Egypt

The exodus itself occurred miraculously by God’s “hand,” but the people had to prove that they were willing to remove the exile from within themselves. This was achieved through acts of self-sacrifice and by demonstrating that beneath the veneer of bondage there existed a resilient and vital spirit ready for redemption.

The bondage in Egypt was not only physical; it was also, and even to a greater extent, mental. The people no longer believed in the possibility of redemption. When Moses came and announced the imminent redemption, the Israelites “did not listen to Moses due to shortness of breath and hard labor.”

If this mental bondage truly dominated the people of Israel, they would not have been able to be redeemed. Only acts of self-sacrifice proved that the people were ready for redemption, despite the fatigue and apparent despair.

Acts of self-sacrifice may seem like a characteristic of challenging situations. Our soldiers serving in the army and fighting valiantly in battles sacrifice themselves for the sake of the people of Israel. But how does self-sacrifice relate to the normative person living a comfortable life? Are we required to reach emergency situations to discover our capacity for self-sacrifice, or is it a trait we can embody in our daily lives?

Upon closer examination, self-sacrifice is not only expressed when people literally risk their lives in a dangerous situation. One can sacrifice oneself in everyday life by surrendering one’s will, overcoming temptation, and doing what one has no desire to do – sacrificing the self for the sake of values, Judaism, and our humanity.

When we resist the inclination to ignore others’ distress and take time out of our schedule to help them, we sacrifice ourselves to some extent for their sake. When we refrain from participating in an event that does not align with our worldview, we sacrifice ourselves for the sake of those values.

As in this week’s Torah portion Shemot, this self-sacrifice is also an educational act. Where did Moses draw the strength to go out and see his brothers in their distress? From the behavior of his mother, Yocheved; his sister, Miriam; and Batya, Pharaoh’s daughter, who raised him in her house.

When we sacrifice ourselves for the sake of others, we educate our children not to be self-centered. When we give up something for the sake of our values, we educate our children not to be hedonistic. When we make a sacrifice for the values of Judaism, we educate our children in devotion and faithfulness. ■

The writer is a rabbi of the Western Wall and Holy Sites