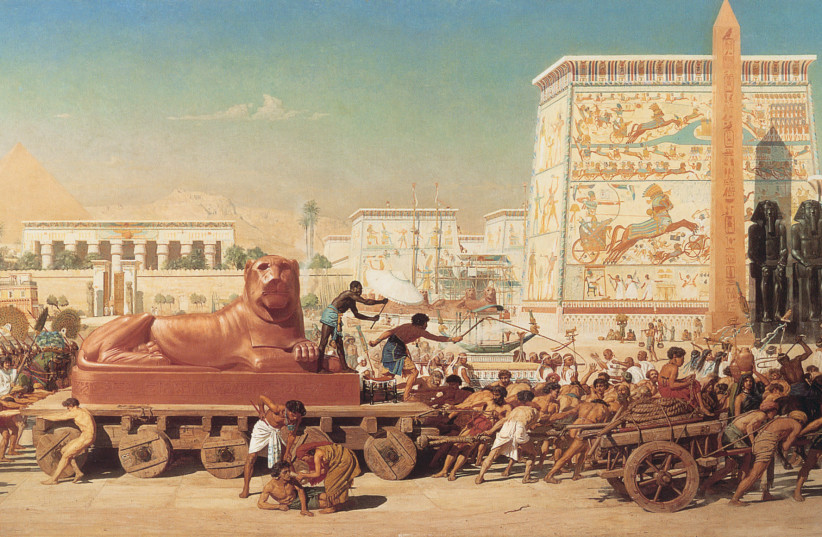

In this week’s Torah portion, we read about the first significant event in the history of the Jewish people – the Exodus from Egypt.

The Torah describes this event with grandeur, as expected: “The Children of Israel journeyed from Ramses to Sukkot, about 600,000 men on foot, besides the young children... and the habitation of the Children of Israel, who dwelled in Egypt, was 430 years. And it came to pass at the end of 430 years, in that very day, it came to pass, that all the legions of the Lord went out of the land of Egypt” (Exodus 12, 37-41).

At first glance, these verses explicitly mention the duration of time that the Children of Israel spent in Egypt: 430 years. However, our sages and Torah commentators calculated this and proved that it is incorrect.

How long did the Jews spend in Egypt?

According to their calculations, the Children of Israel were in Egypt for 210 years. The number 430 includes the time from the days of our forefather Abraham, who had also lived for a time in Egypt. However, in reality, from Jacob’s descent to Egypt until the Exodus, no more than 210 years passed.

The proof that the Children of Israel were in Egypt for only 210 years, and not 430, is explained extensively by Rashi. The calculation is based on the lifespans of Moses and his ancestors, briefly summarized as follows: Kohat descended to Egypt with Jacob, as explained in the Book of Genesis. Amram, his son, lived in Egypt, and Moses, the son of Amram, led the Children of Israel out of Egypt when he was 80 years old. Even if we consider the combined lifespans of these three individuals, we would still only account for 350 years. This calculation is, in any case, misleading because a person is not born in the year his father dies but rather many years before. Consequently, we are forced to conclude that the Children of Israel were in Egypt for fewer than 350 years, and according to the tradition of our sages the actual duration was 210 years.

One of the great early 20th-century Jewish scholars of Eastern Europe was Rabbi Yosef Rosen, who lived in Daugavpils (formerly Dvinsk) in Latvia. Legends about his genius circulated during his lifetime, and his books are still studied today. Rabbi Rosen made a surprising suggestion that both numbers (430 and 210) can be reconciled.

According to him, if each generation is considered separately, without subtracting the years when a father and son lived simultaneously, we arrive at the precise number of 430 years! The detailed calculation is somewhat intricate, so we will provide only an example of the process: If Amram lived for 137 years, and Moses lived for 80 years until the Exodus, we count these years as (137+80) 217 years, even though practically, Moses lived alongside his father for many years. By means of this original calculation of the generations from the descent to Egypt until the Exodus, we reach the exact number of 430 years.

But why calculate the years this way? Is it not true that a person is not born in the year his father dies? If Moses was born when his father, for example, was 20 years old, then practically, the time that passed from the birth of Amram’s son until the Exodus was only 100 years. What is the logic in counting the years of each generation separately when, in fact, they lived during some of the same period?

If we delve into this, we discover a unique perspective on history. One can view history as a sequence of years and events. In this view, humans are not at the center, but time and chronology are. This perspective is how we see history.

However, there is another perspective, where the story is the story of people. Each person lives in a specific time frame and experiences unique and personal events, challenges, insights, difficulties, and successes throughout his/her lifetime. It is not correct to count the years of several individuals together, since each one of them is a complete, unique world deserving to be counted on its own.

According to this perspective, a father and son living side by side are worthy of being counted as two separate time periods – the father’s life on its own, and the son’s life on its own. Since every person lives in a unique world, counting his/her years separately honors the singularity of his/her experiences.

We must never forget that each person’s life is irreplaceable. What we do not accomplish, no one else will achieve in our place. The challenges that each and every one of us overcome are those that no one else could. The failures are ours, and so are the successes.

If we embrace life in this way, understanding the power of our uniqueness, it will give us strength and motivation to succeed in every challenge. ■

The writer is rabbi of the Western Wall and holy sites.