There is an old Jewish joke about a man in a restaurant who complains incessantly about the food. He has a litany of grievances: “it tastes awful, it doesn’t smell good, it is insufficiently cooked” and so on. Finally, he concludes, “and such small portions!”

Something similar happens in the life of leadership. How often have I heard rabbis and other leaders complain about the attitudes of their congregants, the difficulties and trials of dealing with a community, and how they long for fewer burdens. Yet when the time is up, they desperately want more time to lead.

That is beautifully conveyed in this week’s parasha. Moses receives confirmation from God that he will not be able to enter Israel: “Ascend these heights of Abarim and view the land that I have given to the Israelite people. When you have seen it, you too shall be gathered to your kin” (Numbers 27:12).

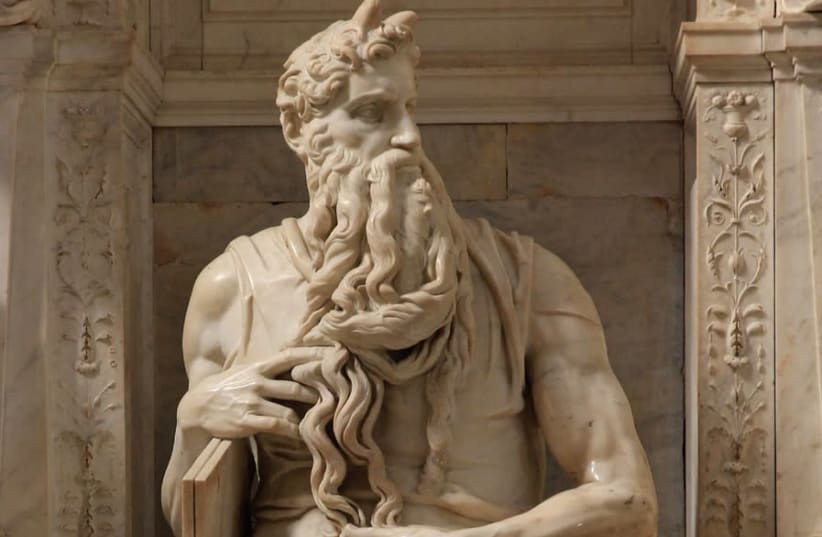

In reaction to this we would naturally expect Moses to protest, to cry out, to shake his fist at the sky. Such small portions! He has worked so long and so hard, only to have God confirm his death in the wilderness. Indeed, there is an entire midrash, Midrash Petirat Moshe, (Midrash on the Death of Moses), that imagines the sort of protest and plea Moses might make before God.

Yet Moses’s reaction in the Torah is very different: “Let the Lord, source of the breath of all flesh, appoint someone over the community who shall go out before them and come in before them, and who shall take them out and bring them in, so that the Lord’s community may not be like sheep that have no shepherd (Numbers 27:15-17).”

Moses’s first concern is for Israel, not for himself. At the moment when he faces his own mortality, Moses chooses to call God, “source of the breath of all flesh.” In other words, I acknowledge God that you have given me life and have the right to decide when it be taken away. I do not make my plea for a new leader on the basis of resentment, but rather from reverence and acceptance. Then comes the wonderful double formulation: go out and come in – the new leader must first be someone who will take upon himself the responsibility to go before Israel, like a modern general in the IDF, leading the charge; and someone who will also be the leader in declaring the battle or the mission over – who will come in before them. “Take them out and bring them in” – yet it must also be someone who has the charismatic power to persuade Israel to follow. It would be hard to summarize the essentials of leadership in a more succinct manner.

Moses is not satisfied merely to ask that a leader be appointed, however. When God chooses Joshua, the instruction is clear: “Single out Joshua son of Nun, an inspired man, and lay your hand upon him… invest him with some of your authority.” (Numbers 27:18,20). What does Moses actually do? “Moses did as the Lord commanded him… he laid his hands upon him” (22,23). God sought to spare Moses, saying to place a hand on him, give him some of your authority. But Moses full-heartedly placed both hands on Joshua. He knew that the greatest gift he could give to Israel was to express full confidence in his successor.

There is a deep disappointment in Moses’s being denied entrance into Israel. Nonetheless a moment of great pain is also a moment of self-transcendence. In Deuteronomy, Moses tells the people, “I stood between you and God (5:5).” The Kotzker Rebbe said this teaches us that often the “I,” the ego, stands between us and God. The same Moses from whom this lesson is derived was able to put his ego aside for the good of Israel.

May we learn his lesson in our own day.

The writer is Max Webb Senior Rabbi of Sinai Temple in Los Angeles and the author of David the Divided Heart. On Twitter: @rabbiwolpe.