Israel’s policy towards Russia and the Ukraine crisis is a high-wire acrobatic act: trying to balance principles on one hand and interests on the other; doing right by the Ukrainians without inciting Moscow’s anger – an anger that could trigger Russian actions that might significantly harm Israeli security.

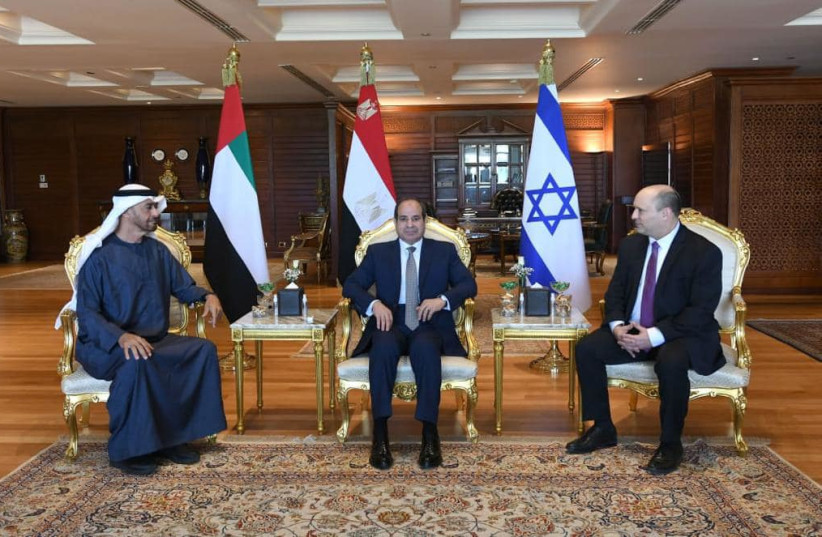

But this acrobatic act is not the only one Prime Minister Naftali Bennett is engaged in, as borne out by his trilateral meeting in Sharm e-Sheikh Tuesday with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (MBZ).

There, too, Bennett is walking a tightrope between wanting to solidify relations with regional powers deeply disappointed by a US desire to enter a new nuclear deal with Iran at seemingly any cost, and not wanting to go overboard and incite Washington’s anger – an anger that could trigger US actions that harm Israeli interests.

Why should the US look askance at such a summit?

First of all, because it took place five days after MBZ hosted none other than Syria’s President Bashar Assad in Abu Dhabi, the first visit by Assad to an Arab country since the civil war began in Syria in 2011, and part of an apparent effort to bring him back into the embrace of the Arab world.

State Department Spokesman Ned Price said the US was “profoundly disappointed and troubled by this apparent attempt to legitimize” Assad. And that invitation came just a day after the United Arab Emirates foreign minister went to Moscow to meet with his Russian counterpart.

That one-two punch, that double poke in Washington’s eye, comes against the background of UAE dismay that the US is not taking a stronger stand against Houthi drone and rocket attacks against it and Saudi Arabia, as well as anger that Washington is not only about to sign a deal with Iran, but is also flirting with the idea of taking the Islamic revolutionary Guards Corp off its terrorist list, just as they did to the Houthis.

But the anger runs both ways, with the US unhappy that the UAE – a temporary member of the 15-seat UN Security Council – did not vote to condemn Russia early on in the Ukraine war at the Security Council, and that MBZ – along with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman – have rebuffed US appeals to increase oil output, and reportedly even refused to take calls recently from US President Joe Biden.

In other words, Israel’s leader met with the ad hoc head of the United Arab Emirates to coordinate policy and positions at a time when UAE-US relations are not exactly soaring. Or, as UAE Ambassador to Washington Yousef al Otaiba recently put it, when relations between the two countries are undergoing a “stress test.”

US relations with Egypt are also facing challenges, as the US withheld $130 million in military assistance to Egypt in January because of human rights violations.

Much has been written and discussed about Bennett’s mediation efforts between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Ironically, his mediation might be needed between the US and the UAE as well.

And that is not as outlandish an idea as it might appear at first blush, as Washington reportedly turned to Israel a few weeks back after the UN Security Council resolution, and asked its help in getting the UAE to support a similar resolution in the General Assembly (it did). But think of that for a moment: Washington looked to Israel to lobby the UAE.

VERY LITTLE could be gleaned about what happened at the surprise Sharm summit by the laconic statements put out by each of the three countries involved.

The Prime Minister’s Office said that the leaders spoke of the relationship between the three countries and how to strengthen them in light of global and regional events. The Egyptians said that the three men discussed ramifications of global developments, especially in the realm of energy, market stability and food security. And the UAE statement echoed that of the Egyptians.

With only those as the official communique, it will take a while, if ever, before a full and accurate description of what happened at that summit emerges. But even without a clear readout, the very fact the summit took place sent unmistakable messages to different actors.

To the US the signal is simple: Your determination to re-enter the Iranian nuclear agreement without addressing the issue of Iran’s ballistic missiles, drones, and support for proxies undermining stability throughout the region – from the militias in Iraq to the Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza and the Houthis in Yemen – will force those countries in the region threatened by those ballistic missiles, drones and proxies to band together to thwart Iran’s designs.

One key country not at the Sharm meeting – Saudi Arabia – sent an even stronger message to the US by inviting Chinese President Xi Jinping for a visit in the coming months to strengthen ties. All of this taken together signals to the US that the countries of the region – having taken note of the US interest in withdrawing from the Mideast and its determination to sign a deal with Iran – are taking the steps they deem necessary to ensure that this does not endanger their security.

To the Iranians, the message is equally simple: If you think that the signing of a new nuclear agreement and the cash windfall it will bring will allow you to intensify your efforts to destabilize the region, think again. Despite not insignificant differences, the countries in the other major camp in the Mideast aligned against the Iranian camp – Israel and the politically moderate Sunni states – will cooperate closely to thwart Iranian designs, even if, for instance, they don’t agree on the Palestinian issue.

And to the Palestinians and the rest of the world, there is also a message: While America’s traditional Arab Mideast allies may be slowly drifting away from Washington, this is not being accompanied by a corresponding drift away from Israel. Though the US was instrumental in brokering the Abraham Accords, and Washington’s willingness to sell F35s to the UAE helped facilitate it, that the UAE and the US are now pulling away from each other is not leading the UAE to break away from Israel.

Abdel Bari Atwan, the fiercely anti-Israel editor-in-chief of the London-based electronic Arabic daily Rai-al-Youm, wrote following the Assad trip to the UAE that it was one sign of the US losing its status and influence in the Middle East, something he applauded in part because “turning against the US also implies turning against Israel.”

Tuesday’s trilateral summit in Sharm e-Sheikh, however, proved him wrong. That the leaders of Egypt and the UAE met at this time with the Israeli prime minister indicates not that a drift from the US presages a drift from Israel, but rather the opposite: Since the US is not viewed now as reliable an ally as it once was, this is the time to move closer to Israel to counter common threats.