Don't go to Turkey.

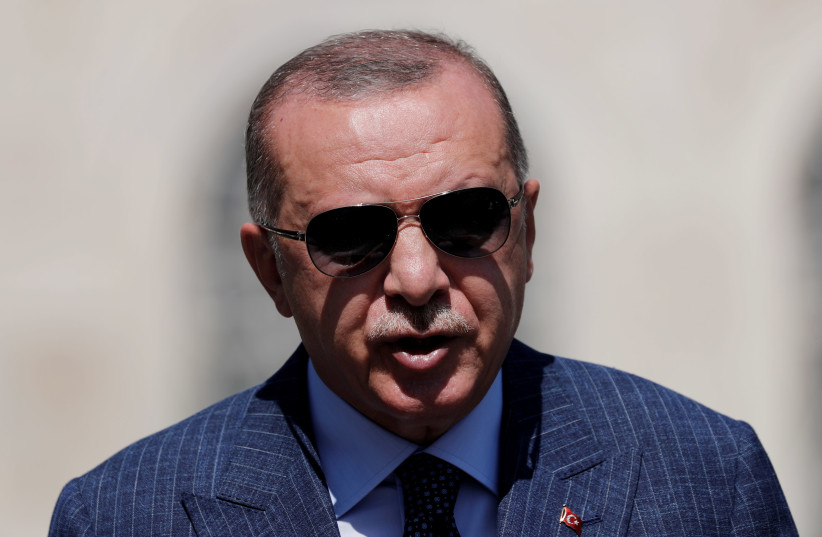

That should be the government’s message to all Israelis if the Turkish authorities do not immediately release the Israeli couple Natali and Mordy Oaknin from custody for allegedly spying because they took a photo of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s palace from a tower across the street.

And if that is not enough to get the Turks to release the couple, then other, more strident actions should be considered.

Among them: embark on a campaign in other countries – the US, the UK, Germany – warning of what awaits tourists to Turkey if they take a selfie in front of a building about whose sensitivity they are unaware; sanctioning Turkish “charitable” organizations undermining Israel’s sovereignty in east Jerusalem; and even banning flights to and from Turkey.

Israel needs to send a message to Ankara that this type of behavior simply cannot be tolerated and that there is a price to pay. Because if Jerusalem does not act here with determination, then the Oaknins may end up sitting for months in a Turkish jail cell, just as Naama Issachar sat in a Russian jail for 10 months in 2019-2020, and was sentenced to seven and a half years for having some nine grams of marijuana in her luggage on a return trip from India to Israel via Moscow.

Russian President Vladimir Putin was not necessarily looking for an Israeli to hold when Issachar fell into his lap – but once she did, he used her for leverage with Israel in an apparent effort to keep Jerusalem from extraditing Russian computer hacker Aleksey Burkov to the US (the High Court of Justice did ultimately order Burkov’s extradition).

The price Israel paid for Issachar’s release – Putin pardoned her just prior to the March 2020 election – was never made public, but speculation was rife, ranging from turning over ownership of church property in Jerusalem’s Old City to Russia, changing the route of the planned light rail in Ein Kerem to skirt property owned by the Russian Church, handing over parts of the “Russian Compound” in Jerusalem to Moscow, or maybe scaling back IAF actions at the time over Syrian airspace.

Erdogan is now apparently taking a page out of Putin’s playbook. If Israel does not take strong action to put an end to it, who knows when he may do so again? Just three weeks ago the Turks trumpeted that they had arrested a Mossad cell of 15 non-Israeli Arabs working with the Mossad. Fifteen men in October, an Israeli couple in November – who knows what December may bring?

Two years ago, when Issachar was finally released and flown back to Israel on former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s plane, these lines were written in The Jerusalem Post:

“Might the way Israel responded to Issachar whet the appetite of Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan or some unsavory and hostile character in the Jordanian government to nab an Israeli traveler to be used for leverage for something they want from Jerusalem?”

One did not have to be an oracle to make that prediction. And Erdogan wants plenty from Jerusalem. He wants a foothold on the Temple Mount and he also wants easements for Gaza for which he wants the credit. His entire, long reign in power has been an effort to come across as the defender and protector of the Palestinians and Jerusalem, to gain stature in the Arab and Muslim world.

And, at times, it has worked wonders. In 2009, he was viewed as a hero in much of the Arab world after storming out of a joint appearance with then-president Shimon Peres at the World Economic Forum in Davos following Operation Cast Lead in Gaza. In 2010, he rode the Mavi Marmara incident to even greater popularity in the Muslim world.

Erdogan has also honed his Israel bashing into an art form before Turkey’s elections – national and municipal – with slamming Israel and Jews often a telltale sign under Erdogan that elections are around the corner.

As then-deputy foreign minister Tzachi Hanegbi put it in 2014, Erdogan and other top officials of his party employ the “manipulative, populist tactic of insulting Jews” before each election.

AND ELECTIONS are not that far off – June 2023. After serving now for some 19 years as Turkey’s strongman, Erdogan is limping to those elections, with his party’s popularity at about 30%, some 10% less than during the last elections in 2019.

Unemployment is at 10%, inflation at nearly 20%, and the lira dropped on Thursday to historic lows against the dollar, losing two-thirds of its value over the last five years, thrusting thousands of Turks below the poverty line.

In short, Erdogan’s political situation is precarious. What better way to divert attention than to arrest Israeli “spies” month after month?

But Israel need not serve as Turkey’s whipping boy; Ankara also stands to lose by getting into a diplomatic spat with Jerusalem.

First of all, with its economy reeling, Turkey enjoyed a $2 billion trade surplus with Israel in the first nine months of this year. Also, Israelis – at least until the Oaknins were arrested – were traveling to Turkey, a not insignificant component of Turkey’s tourism industry. In 2019, before COVID-19, Israel was ranked 16th on the list of the country’s feeding tourists to Turkey. And in October, Turkey was the second most popular destination for traveling Israelis – following the US.

Of the 383,000 Israelis who left the country last month, 11.5% went to Turkey. The Israeli tourist trade is not going to make or break the Turkish economy, but with the economy in trouble and the coronavirus wreaking havoc on the tourist industry, Turkish merchants who rely on Israelis definitely do not want to lose that share of the market.

This is why the threat of strongly advising tourists against going to Turkey should be used if the Oaknins are held much longer.

It will not be enough to issue a travel advisory warning against travel to Turkey: Such an advisory has, in fact, been in place since 2017 – but is widely ignored.

Turkey is currently listed by the counter-terrorism bureau in the National Security Council as a country where there is a “high concrete threat” to Israelis, one of 16 countries with this classification, along with states like Algeria, Lebanon, Pakistan and Tunisia.

Of the five levels of threat, this is the second-highest. The highest threat level is countries in the “very high concrete threat’’ category which includes states like Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Syria.

Despite the travel warning in effect regarding Turkey, thousands of Israelis – including a large number of Israeli Arabs – are still booking packages to the country, confident that the type of concrete threat that the NSCs counter-terrorism unit is warning against – terrorism – will pass over them.

As of last week, however, terrorism is not the only threat facing Israelis in Turkey. Now they are also facing actions by the Turkish authorities themselves – and that is something Israel’s government has a responsibility to warn its citizens against in the strongest of terms if the Oaknin affair is not resolved soon: Don’t go to Turkey because you may be arbitrarily picked up by the police and thrown into jail on trumped-up “espionage” charges.