In the hands of Gary Goldstein, book covers and pages from a world atlas are transformed into colorful portraits of smiling, handsome, men and women seemingly posing for a yearbook photo, as explosions, vampires, and super-heroes hover near them like putti (“winged children”) around a deity in an ancient fresco.

Visitors to “Running Up the Wall,” now at the Petah Tikva Museum of Art, may examine blocks of carefully lettered words that bulk up these beaming miens. The transformed data sheets, with their exchanged promise of offering real-world knowledge, returned to us as accurate seismographic readings of the artist’s inner world, giving way to graphic depictions from the Korean War, Asian theme works, and a Kunstkammer of objects that US-born, Tel Aviv-resident Goldstein made, lost, and recreated for over two decades.

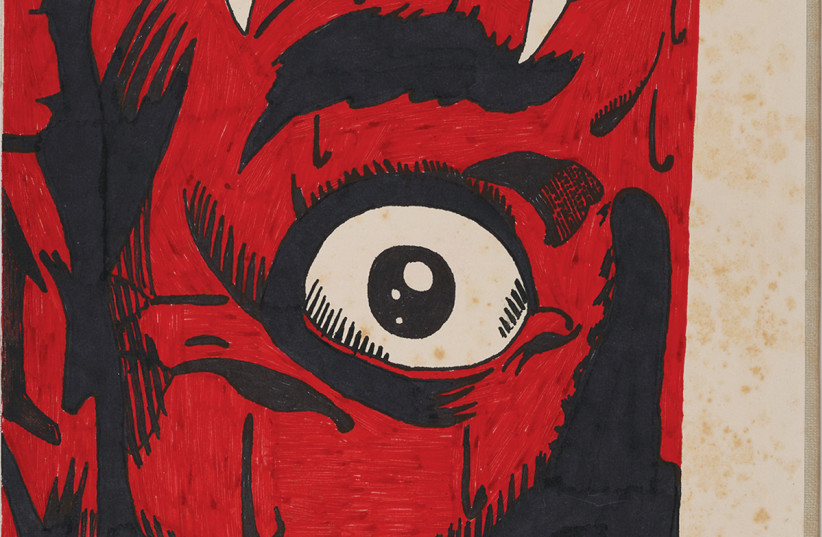

Inside the glass cabinet of curiosities, we see a postcard of the crucifixion on which the artist has painted a spirit with dripping breasts; a jaw; a black-and-white Star of David with the word “Jude” painted on it; glasses with painted eyes; eyeballs removed from their sockets; and a one-legged Mickey Mouse.

“These are but a small selection of all the objects,” Goldstein tells The Jerusalem Post. “Over the years I made many – and in storage and moving processes they were sometimes damaged. My work is very fragile and ephemeral. It causes pain to watch works destroyed, it is an archive of memories, my own,” he says.

Reminders of death paired with elaborate gaiety

The sometimes ghoulish objects are poised at the crossroads between a memento mori, a somber reminder of the black borders of death which encase all our lives, and the gaiety of a día de muertos celebration or a Tim Burton production.

While pacing around the display case, I cannot help remembering The Collector, a 2021 video artwork by Nevet Yitzhak which animated the figurines collected by Wilfrid Israel. I wonder if the power in these objects would be served by such a cooperation, or whether it was better for the mind of each viewer to animate these on her or his own.

Getting to the Petah Tikva Museum of Art requires crossing the various construction projects surrounding it and a nod to the entrance guard, busy sketching portraits of his own.

Shown in the context of eight other exhibitions (among them, Mordecaï Moreh’s “An Almost Sane World” and “Four Days, One Horizon” by Noa Gross and Ori Noam), Goldstein maintains his unusual position, a distinctly Jewish-American note in a highly Israeli symphony.

Some Israeli artists and critics pride themselves on once obtaining some education in the US. Israel Hershberg for instance, a US-trained figurative painter of note, was shocked in the late 1980s when he was introduced to an art student here and realized the man was blind.

At that time, the Israeli art scene had a sort of uniformity: whether a person could see or sketch properly was not regarded as important as the spiritual or intellectual aspect of the work being produced.

Now “the Israeli art scene is both smaller and much larger, and much more open,” Goldstein tells the Post.

Whereas the late artist Pesach Slabosky used jeans to paint art (1996, Chelouche Gallery for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv) as a way to deal with his American homeland – Goldstein brings up war comics from the 1950s that dealt with the Korean War.

“These were published in real-time,” he points out, “and the target audience was teenage boys. After WW2, the US Army was used to guard duties in Germany and Japan; and when they got to Korea “it was a catastrophe,” he says.

In that sense, Goldstein’s art is a powerful reminder that the old truths of the past should not be easily overlooked, even while we rush toward an unknown tomorrow.

“Look at Ukraine,” he says. “People said major tank battles were finished and that wars would be cyber-wars, that territory has no meaning – this has been proven wrong.”

In his “Atlas” series, Goldstein always deals with borders and the lack of borders. “I cover all the information in the map,” he says, “and create my own emotional reaction to the map and the border.”

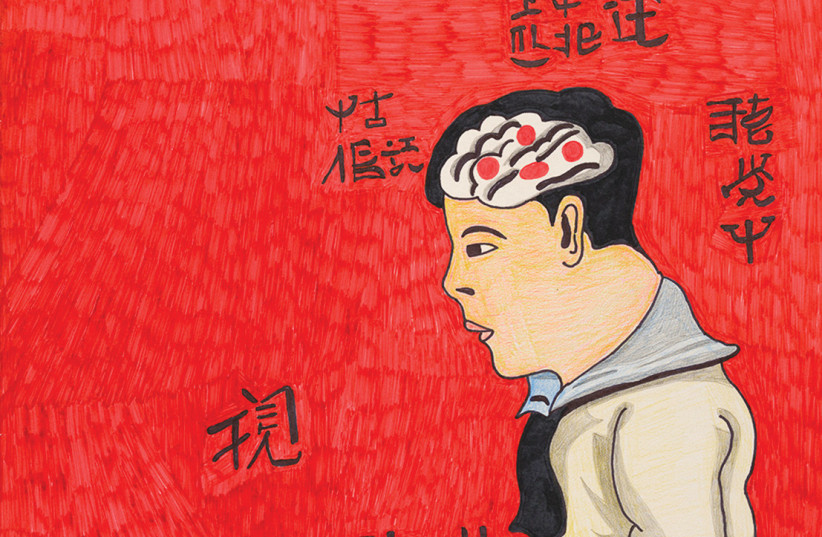

This is why it is surprising to see that in the “Asian” series, the heavy text blocks are replaced by Chinese characters that few art lovers here will be able to read. The borders seem to have been replaced with fields of color. For Goldstein, this series was inspired by reading reports of various “China hands,” Westerners who speak and read Chinese and had attempted to live there and gain some insights into its inner working – mostly without much success.

“This feeling of not understanding,” he shares, “accompanies me all the time.”

Working at home on a table – much like his father made garments – Goldstein maintains a work ethic that is both very Jewish and deeply moving.

“The actions do not have importance” by themselves, he explains, “but the work does.”

Through the work, his art, the finished paintings, and objects he makes slowly and carefully by hand, “I can speak about my family, history, memories,” Goldstein says.

“This offers a connection to the sublime and to the metaphysical.”

Running Up the Wall by Gary Goldstein (Curated by Reut Ferster and David Frankel) will be shown through October 16, 2023. The Petah Tikva Museum of Art, 30 Arlozorov St.; Mon, Wed, Fri, Sat (10 a.m.-2 p.m. and 4 p.m.-8 p.m.) NIS 30 per ticket. (03) 928 6300