Beliefs in witchcraft – the ability of certain people to intentionally cause harm via supernatural means – have been documented all over the world, going back to the 16th century, when King James I of Scotland’s fear of witchcraft began stirring up national panic resulting in the torture and death of thousands.

But it still exists in the 21st century and does not conflict with a belief in God and religiosity, according to a new study published under the title “Witchcraft beliefs around the world: An exploratory analysis” in the journal PLOS ONE by economics Prof. Boris Gershman of American University in Washington, DC

His newly compiled dataset quantitatively captures witchcraft beliefs in countries around the world, enabling the investigation of key factors associated with such beliefs. Gershman found that belief in witchcraft is positively correlated with faith in God and religiosity. Overall, 62% of believers in witchcraft consider themselves Christian and 27% Muslim.

Born and raised in Moscow, Gershman emigrated to the US in 2007. He earned his doctorate at Brown University in Rhode Island and has since focused on the determinants of long-term economic growth and the development and the economics of culture.

The most famous witch trial in history occurred in Salem, Massachusetts during the winter and spring of 1692/1693. When it ended, 141 accused of witchcraft, both men and women, were tried. Nineteen were executed by hanging, and one was pressed to death by heavy stones. Accused witches were usually women who were thought to have attacked their own community and often to have communicated with evil beings. European belief in witchcraft gradually dwindled during and after the Age of Enlightenment. Still, countries like Saudi Arabia continue to use the death penalty for sorcery and witchcraft.

Witchcraft in Judaism

Jewish law views the practice of witchcraft as being affiliated with idolatry and/or necromancy (the claim to communicate with the dead and predict the future). Maimonides strongly denied the efficacy of all methods of witchcraft and claimed that the biblical prohibitions regarding it were precisely to wean the Israelites from practices related to idolatry. It was acknowledged among Jewish thinkers that while magic exists, it is forbidden to practice it on the basis that it usually involves the worship of other gods.

Numerous prior studies conducted around the world have documented people’s beliefs in witchcraft, wrote Gershman, so “understanding people’s witchcraft beliefs can be important for policymaking and other community engagement efforts. However, due to a lack of data, global-scale statistical analyses of witchcraft beliefs have been lacking.”

"Due to a lack of data, global-scale statistical analyses of witchcraft beliefs have been lacking.”

Prof. Boris Gershman

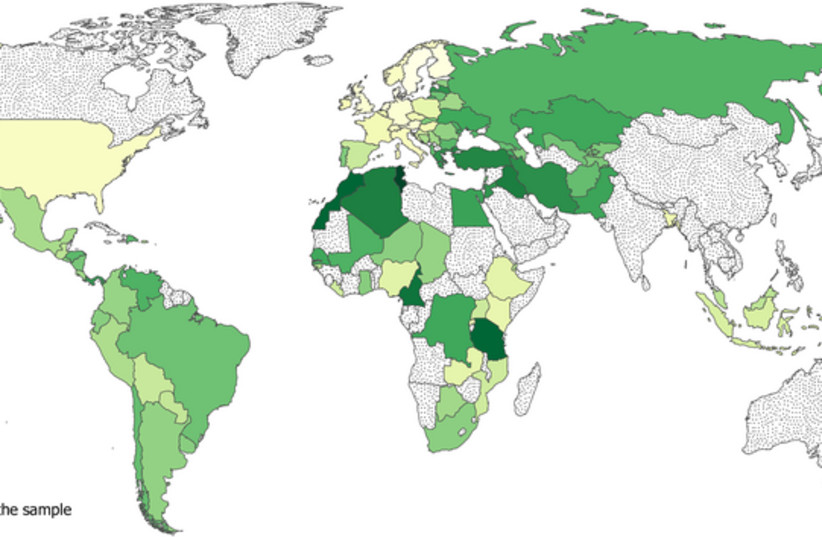

He collected data that captures such beliefs among more than 140,000 people from 95 countries and territories. The data come from face-to-face and telephone surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center and professional survey organizations between 2008 and 2017, which included questions about religious beliefs and beliefs in witchcraft.

According to the dataset, over 40% of survey participants said they believe that “certain people can cast curses or spells that cause bad things to happen to someone.” Witchcraft beliefs, he continued, “appear to exist around the world but vary substantially between countries and within world regions. For instance, nine percent of participants in Sweden reported belief in witchcraft, compared to 90% in Tunisia.

He then investigated various individual-level factors associated with witchcraft beliefs and found that while beliefs cut across socio-demographic groups, people with higher levels of education and economic security are less likely to believe in witchcraft. Such beliefs differ not only among countries but according to various cultural, institutional, psychological and socioeconomic factors. For instance, witchcraft beliefs are linked to weak institutions, low levels of social trust, and low innovation, as well as conformist culture and higher levels of in-group bias – the tendency for people to favor others who are similar to them, he wrote.

These findings, as well as future research using the new dataset, could be applied to help optimize policies and development projects by accounting for local witchcraft beliefs. “The study documents that witchcraft beliefs are still widespread around the world and their prevalence is systematically related to a number of cultural, institutional, psychological, and socioeconomic characteristics,” the study concluded.