At the beginning of the current Ukraine-Russian crisis, the following statement attributed to a senior Israeli official appeared in the not uninfluential American news website Axios: “We love Ukraine, but we are not going to get involved in a conflict between superpowers like the US and Russia. We have enough on our plate.”

From multiple perspectives the quote is problematic, its three consecutive segments demanding dissection and illumination.

<br>First: “We love Ukraine.”

Israel and the Ukraine have had a good bilateral relationship, but a historic perspective invites a more judicious use of language. From the Bohdan Khmelnytsky massacres of Jews in the mid-seventeenth century (Khmelnytsky is regarded as a Ukrainian national hero today), through to the civil war White pogroms that followed the Bolshevik revolution, the ties between Jews and Ukrainians contain multiple elements in addition to love.

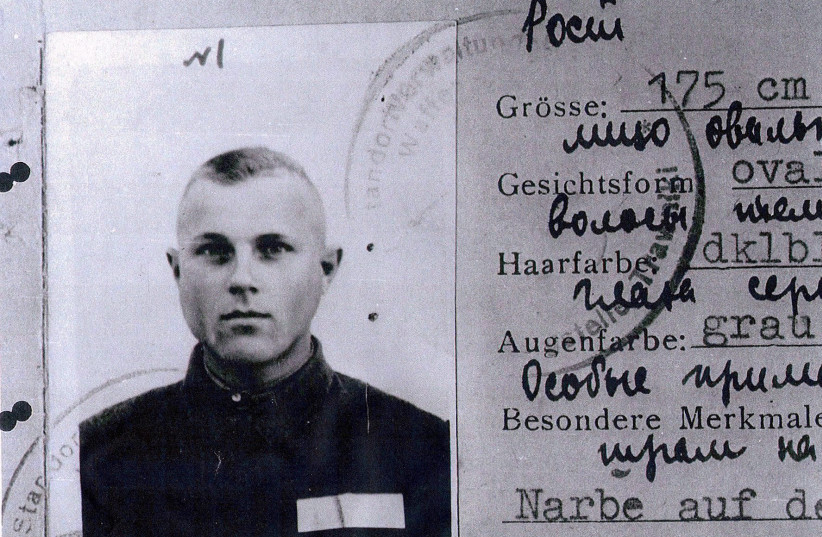

During the Second World War, many Ukrainians actively collaborated in the Holocaust, whether through the Ukrainian fascist movement the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), the Waffen SS Galicia Division or the Schutzmannschaft auxiliary police. The trial in Israel of John Demjanjuk showcased one of the many Ukrainians who served as concentration camp guards.

Irrefutably, the Ukrainians were victims of mass murder, as well. No one can read Anne Applebaum’s Red Famine and not appreciate the scope of the tragedy, Stalin’s forced starvation killing some five million Ukrainians in the early 1930s. But empathy for past Ukrainian suffering cannot excuse present-day Ukraine’s glorification of Nazi collaborators.

The 2019 election of a Jewish president powerfully demonstrated the limited traction of contemporary Ukrainian antisemitism, but the “we love Ukraine” Tourism Ministry-type phrase was nonetheless ill-chosen. It would have been more appropriate for a representative of the Jewish state to adopt more nuanced language better reflecting Israel’s friendly relations with the modern Ukrainian democratic state.

Moreover, expressing love, when the intention is to explain why Israel is not going to lift a finger to help, could be seen as hypocritical and patronizing.

<br>Second: “We are not going to get involved in a conflict between superpowers like the US and Russia.”

This sentence could be construed as proclaiming a completely new Israeli foreign policy, signaling that Jerusalem is embracing Nehruist non-alignment or Swiss-style neutrality.

It is true that Israel has established a special dialogue with Russia. Developed under former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and currently being continued by Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, Israel has built a vital avenue of communication with the Kremlin.

This channel has become especially important since 2015, when Moscow’s expanded its military presence in Syria, demanding Israel reach practical understandings with the Russians to enable the IDF’s continued freedom of action against Iranian and other targets in that country.

Here realpolitik considerations are augmented by historic memory, the recognition of Russia’s indispensable role in the defeat of Nazi Germany. While in much of Eastern Europe (Ukraine included) the Red Army is often synonymous with decades of foreign imposed despotism, Jews honor the Soviet troops who liberated Auschwitz in January 1945 and smashed their way into Berlin that April (incurring casualties that vastly overshadowed the losses of the western allies).

Yet, this crucial dialogue with Russia in no way negates Israel’s commitment to the West. The ever-expanding strategic partnership with the United States (US) is indisputably at the core of Israel’s national security.

Correspondingly, over the past decade, Israel’s relationship with NATO has also been upgraded. Officially a NATO partner, Israel cooperates with the western military alliance in areas such as intelligence, counterterrorism and cyber.

When Jerusalem and Moscow communicate, they do so in the full knowledge that Israel is unquestionably linked to the US. In fact, Israel’s effective engagement with Russia is based on Moscow’s appreciation of the Jewish state’s military, diplomatic and technological prowess, strengths stemming from Israel’s position as a key US ally and an integral part of the West.

Naturally, being unequivocally in the Western camp doesn’t demand Israel adopt a high profile in the current Ukrainian crisis; Russia’s presence in Syria necessitates maintaining open lines of communication with Moscow. However, nobody should have any illusions that when it comes to superpower rivalry, Israel is either neutral or non-aligned. The senior Israeli official was mistaken to indicate otherwise.

<br>Finally: “We have enough on our plate.”

The impression given is that Israel is too preoccupied to deal with a major international crisis, even though any escalation in East-West tensions can directly affect the Middle East.

Furthermore, since January, there have been endless government meetings about the Ukraine, culminating in public calls by both the prime minister and the foreign minister urging Israeli nationals to leave the potential war zone before it’s too late. Despite having “enough on our plate” Israel is patently devoting numerous working hours to the situation. Suggesting we don’t have the time or the focus is nonsensical.

Still, it may be comforting to know that a senior Israeli official isn’t necessarily someone of importance. Although the term may be used to describe a member of the security cabinet with decision-making authority, it can also denote a mid-level bureaucrat who is grateful that the working day’s mundane routine is being broken by a journalist asking a question.

Reporters have been known to inflate the importance of their sources. Two decades ago, when I served as the spokesperson for Israel’s Washington embassy, I would be surprised when on occasion a journalist would honor me with the title senior official, maybe in the belief that elevating the status of the source made the story more authoritative.

In addition, when working on a piece, a reporter will not always realize who is in the know. Upon being approached, an official will sometimes not want to lose face in front of a respected journalist by admitting being out of the loop (which professional will voluntarily acknowledge irrelevance?), proceeding to talk with the reporter without having direct involvement in the subject matter at hand, offering what they presume is going on, which is then reported as being definitive.

We do not know who Axios’ anonymous source is, though a search could be initiated for an official who has known affection for the Ukraine, enjoys sprouting independent views and considers themself professionally overburdened. In the best scenario the senior Israeli official is just an irrelevant bureaucrat answering a journalist’s questions to feel important, but if the source is someone of significance, it must be hoped that they are on a learning curve, and that yesterday’s hapless remarks won’t be repeated tomorrow.

The writer, formerly an advisor to the prime minister, is a senior visiting fellow at the INSS at Tel Aviv University. Follow him at @AmbassadorMarkRegev on Facebook.