It is a song known around the world, a national anthem that stirs Jewish hearts from Manhattan to Melbourne, giving voice to the yearnings of generations to return to our ancient patrimony.

Whether it is performed at the start of a basketball game or the swearing-in of IDF soldiers at the Western Wall, “Hatikvah” moves, inspires and challenges us to appreciate how fortunate our generation is.

I must admit that I still get the chills when I hear the first notes of “Hatikvah” being played, as though the chords themselves reach deep inside and touch something within the soul.

And yet, despite its deep familiarity, there is much about “Hatikvah” that appears to be shrouded in mystery, including some of the most basic facts surrounding its provenance.

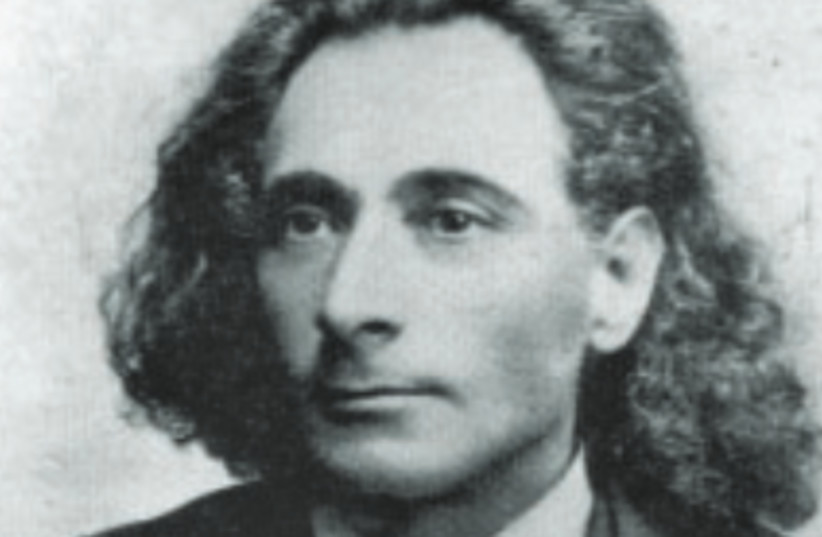

Sure, we all know that it was penned by the Hebrew poet Naftali Herz Imber, a Jew who lived in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the late 19th century, and that it rapidly gained popularity throughout the Zionist movement.

But aside from that, not much else is clear.

For example, scholars disagree as to whether Imber drafted or completed it in Iasi, Romania, in 1877, or perhaps in Zloczow, in what was then Poland, in 1878, or whether and to what extent it was revised once he made aliyah in 1882.

We do know that it was first published in Jerusalem in 1886 in a collection of Imber’s poems titled Barkai, Hebrew for morning star.

As Prof. Edwin Seroussi, winner of the Israel Prize in the field of musicology, suggested in a 2015 scholarly article, titled, “Hatikvah: Conceptions, Receptions and Reflections,” Imber seems to have been inspired by the founding of Petah Tikva.

Yet, as he also notes, the source of the themes and phrasings used in the song is the subject of much debate.

Some theories suggest that it was inspired by German or Polish patriotic songs, while others link it to the biblical vision of the dry bones coming to life in chapter 37 of the Book of Ezekiel.

The inspiration behind the “Hatikvah” melody, which was composed by Samuel Cohen, is also unclear.

Musicologist Astrith Baltsan has said that the tune is linked to a 600-year-old melody sung by Sephardim when reciting the Prayer for Dew.

Others have said that it is based on Italian, Romanian or Gypsy folk songs, or on “Die Moldau,” a symphonic poem by Bohemian composer Bedrich Smetana.

It is also unclear how “Hatikvah” became so widely accepted, or why other competing poems and songs never caught on.

Nonetheless, beginning with the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel in 1901, it was sung at all such gatherings until formally being adopted in 1933 as the anthem of the Zionist movement.

IN LIGHT of the Jewish people’s strong sense of historical consciousness, it is intriguing to consider just how little we know with certainty about Israel’s national anthem, which is less than 140 years old.

But that does not detract at all from its undeniable beauty and imagery. For even as it recalls the pangs of exile, it highlights the portents of our people’s destiny, embodied in that most powerful of human emotions, hope.

The haze surrounding the details of its origins is, in this sense, highly symbolic, hinting at the blur of exile which the Jewish people endured until the founding of the state in 1948.

There are, of course, plenty of people who criticize “Hatikvah,” with some on the Left objecting to its reference to the “Jewish soul,” while others on the religious Right bemoaning its secularity.

But I think we should pay such critics no heed.

In effect, “Hatikvah” serves as a brief and emotive reminder, a sort of “musical mezuzah” that aims to put things in their proper historical and spiritual perspective.

It prompts us to appreciate, if only for just a few moments, the merit granted to us by Divine providence to be reciting a Jewish national anthem in the sovereign Jewish state.

And it serves to underline our determination to be a free people in our own land, “the land of Zion and Jerusalem.”

Like any national anthem, “Hatikvah” embodies the heritage of a people. But unlike others, it expresses a 1,900-year-old dream that came true and one that continues to unfold. ■

The writer is founder and chairman of Shavei Israel (www.shavei.org), which assists lost tribes and hidden Jewish communities to return to the Jewish people.