I have a linden tree in my front yard. Out back we have a magnificent pin oak that must be four stories tall, each of its lower branches as thick as the trunk of a normal tree. We have three northern white cedars on one side of the house, and three flowering dogwoods along the back fence.

I can’t tell you how much pleasure I get from being able to name these plants. Not owning or planting them — for that you can thank the people who sold us the house. I mean naming them. I’ve spent most of my life in a taxonomic fog, barely being able to distinguish an oak tree from a cell phone tower. The only tree I could ever identify with confidence was a weeping willow.

The app that started it all

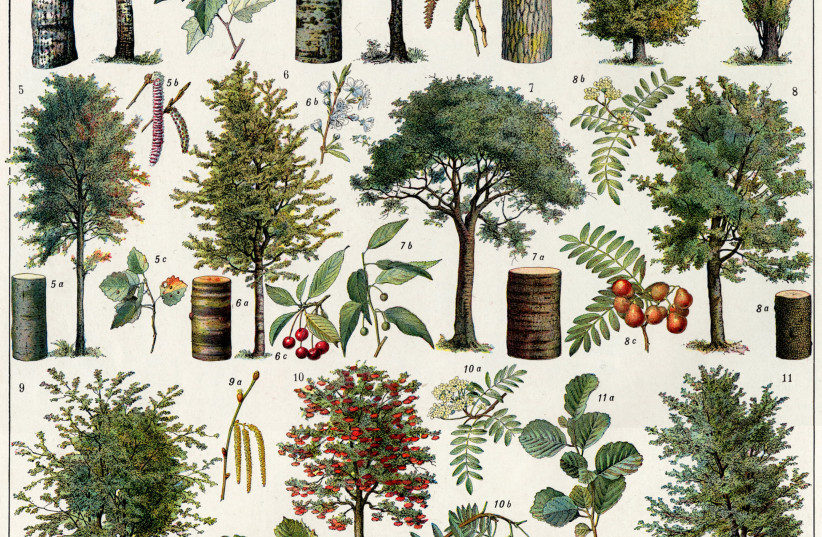

But earlier this year I downloaded the PictureThis app, which is this nifty tool that lets you point your camera at any shrub, tree or weed and learn its name. You’ve read stories about blind people given their sight back, the deaf child hearing the world for the first time. I am like this with plants now. To my delight — and my wife’s embarrassment — I run from plant to plant with my iPhone, shouting “That’s a sycamore! Here’s a sumac! Our neighbors have a Japanese zelkova!”

The app lets you explore your new discoveries and find out the best way to feed and care for them. I am not interested — yet. But I am excited about the whole notion of naming things, and how this basic human impulse changes our relationship with the natural world. The more names I learn, the more the outdoors stops just being the background and becomes a text.

The Torah understands how naming is basic to our humanity. In Genesis, God lets Adam pick names for the animals:

“God formed out of the earth all the wild beasts and all the birds of the sky, and brought them to the Human to see what he would call them; and whatever the Human called each living creature, that would be its name.”

Genesis 2:19

Later commentators understood the impulse to name — and tame — nature as a defining human proclivity. The medieval Spanish commentator Bahya ben Asher suggests that it is our ability to name creatures that distinguishes us from the angels. “This is the meaning of Genesis 2:20: ‘Adam called the names of all the beasts,’” Bahya explains. “All these names Adam gave the beasts were not merely arbitrary names he chose to call them by, but they reflected the essence of each animal respectively.”

A biological perspective

In her 2009 history of taxonomy, Naming Nature: The Clash Between Instinct and Science, biologist Carol Kaesuk Yoon writes that “sorting and naming the natural world is a universal, deep-seated and fundamental human activity, one we cannot afford to lose because it is essential to understanding the living world, and our place in it.”

Well maybe, if you are a herbalist, a gardener or a biologist. But what does naming things mean to the rest of us – the workaday consumers who get their vegetables in the produce aisles, their medicines at a pharmacy and their nature fixes on Animal Planet?

Yoon says it is all about noticing, of raising our consciousness of the flora and fauna that is right out there but that few of us really see. Without naming things, she writes, we are “losing the ability to order and name and therefore losing a connection to and a place in the living world.”

A place that includes greenstem forsythias! Callery pears! Lily magnolias!

I think of naming in terms of “ownership” – for good and ill. Some environmentalists insist that humankind’s toxic relationship with nature begins with Genesis, in which we are told to “fill the earth and master it; and rule the fish of the sea, the birds of the sky, and all the living things that creep on earth.” To be a “master” or a “ruler” is very different from being a “partner” or a “steward.” Assigning a new name is a typical way of exerting control over the body of an enslaved person.

But I also think of ownership in terms of taking responsibility. It’s easier to ignore the needs or desires of other creatures if you don’t know their names — if you don’t see them as individuals. And no, I am not going to call my linden tree “Barry” or my oak tree “Phil.” But with every name I learn, the world seems to snap more sharply into focus. That’s not “a tree”; it is now a particular tree, distinct and distinctive.

I think naming things has also taken on a new importance during the past two years. The pandemic has shrunk our worlds and possibilities. Forced into tight loops of routine, we find the familiar becoming banal. Stare out the same window long enough and you stop noticing the view.

Maybe that’s what Bahya was getting at when he said that Adam gave names that reflected “the essence of each animal respectively.” A name grants a creature its distinctiveness, and the namer the gift of discernment. Or as Yoon puts it, to learn the names of things “is to change everything, including yourself. Because once you start noticing organisms, once you have a name for particular beasts, birds and flowers, you can’t help seeing life and the order in it, just where it has always been, all around you.”

You can’t help seeing a cherry plum! A Montezuma bald cypress! A bed of dwarf crested iris!

I am told there’s an app for identifying birds. I’ll probably get to it, one day. Right now, I have about all the clarity that I — and my wife — can stand.