One year ago, it was nearly impossible to get into the Arab village of Barta’a on a weekend morning. The reason is not security checkpoints or anything in the political sense. The sheer amount of vehicles, Jews and Arab-Israelis alike, notwithstanding the immobile gridlock at the junction of Street 65 by the city of Harish, just to get into one of the best-priced markets in Israel and the Palestinian territories.

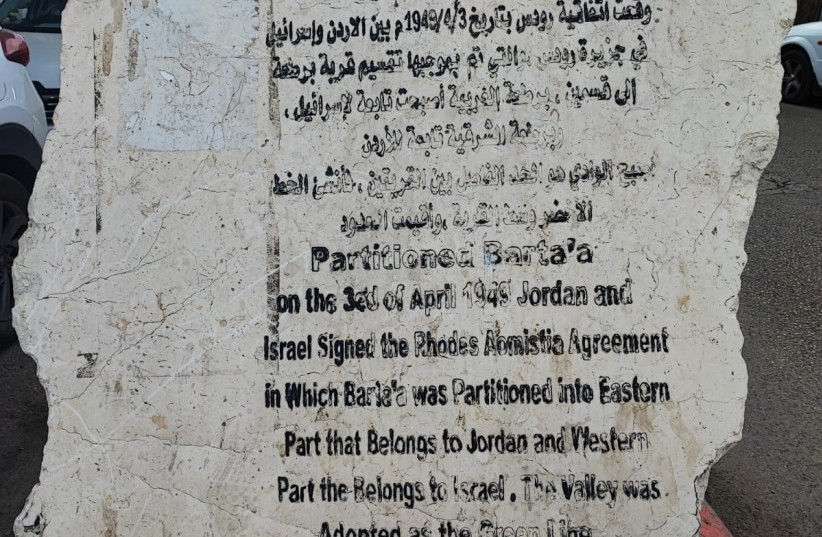

Barta’a is another interesting consequence of the Arab-Israeli conflict. The east side of the village was controlled by Jordan until 1967, when the country lost its western territories to Israel. The village boasts an impressive stone commemorating the old Jordanian border of Barta’a.

The abundant market stretches across Barta’a’s main road, extending from the eastern portion of the village in Israeli territory and into the western portion of the village in Palestinian territory.

Today, there is no wall or barrier to divide the Israeli and Palestinian sides of Barta’a. The only noticeable giveaway that one has crossed over the invisible Green Line is the Palestinian Authority officer casually standing amidst the hubbub and the roundabout further along boasting an array of Palestinian flags.

The bargains, deals and commodities the Barta’a market proudly offers are incalculably less expensive than similar (if not higher quality, in some cases) products sold in Israeli markets. The village boasts a large selection of furniture and clothing imported from Turkey, fantastic prices on car shops, lighting infrastructures, home design, spices, plant nurseries and more.

The price of gas, as it turns out, is unaffected by invisible political borders. Prices on both sides of Barta’a remain about the same as in any gas station in Israel (a whopping NIS 7 per liter, as of late June).

Baqa al-Gharbiyye resident Safila says the only thing she doesn’t buy from Barta’a is fresh fruits and vegetables due to the prices and quality. “The only place I buy my produce is at Rami Levy,” she says laughing. Everything else, she purchases for her family at the Barta’a market.

Barta’a’s local residents are friendly, warm and welcoming to all visitors. Most speak Hebrew, while others, mainly in the eastern part of the village, speak only Arabic and English.

PALESTINIANS WORKING on the Israeli side of Barta’a require a permit to do so, but they say it is not difficult to obtain. Many shop owners and workers can be found from all across the Palestinian territories on both sides of the Barta’a market – from Qalqilya to Jenin, Tulkarm and Nablus.

Still, when 21-year-old Hamza from Barta’a is abroad and asked where he is from, his answer is, “I’m from ’48”, meaning part of the Arabs that were integrated into Israel in 1948. Being from the ’67 Palestine, he explains, is criticized in the Arab world.

Atop one of the side roads parallel to the main street is Haseeba Sweets from the Heart of Nablus, arguably housing the most delicious pastries and knafe in Israel. The shop is run by Baraa and his father, where the only thing sweeter than the mouthwatering desserts they make is their wide-smiled hospitality. Their other branches can be found in various locations in the West Bank.

Today, the streets of Barta’a aren’t empty, but they are no longer jam-packed with cars and eager consumers. The difference is noticeable and many of the locals who rely on the Israeli shoppers are apprehensive.

Maya, who sells women’s fashion apparel in Barta’a with her husband, believes that the corona pandemic took a great toll on the amount of foot-traffic the residents had grown so accustomed to. She does admit, however hesitantly, that the riots of last May have played a big hand in deterring Israelis from buying from Barta’a’s market, despite the village having not been explicitly involved in the violence.

A local tender at one of Barta’a’s plant nurseries, Jamal has a different idea. He believes that many Israeli residents of nearby cities, like Harish, are being dissuaded from doing their shopping in Barta’a as a way to finance the shopping malls and centers of those areas, even though the merchandise Barta’a has to offer is a bargain, in comparison.

Some of the residents are worried that future plans to build a barrier between the west and east sides of the village, or a ban on Israelis (both Jews and Arabs) from entering Barta’a could seriously hurt their economy.

“Look at what they did in Jenin,” says one of Barta’a’s shop-owners, shaking his head in reference to the restrictions on Jenin’s market. “All those businesses are dying and it’s going to have severe effects on everyone.”

There are no plans underway to close off Barta’a or to prevent Israelis from entering. The village is easily accessible with a flourishing market that is open to everyone. Barta’a is possibly the country’s best-kept shopping secret – a low-profile village market with high future prospects.

The author is an independent writer and researcher of current affairs, religion and health in the Middle East. She was born and raised in New York before making aliyah as a lone soldier in 2011, and studied medical science research at Tel Aviv University.