The attempted murder of Salman Rushdie is the result of more than three decades of incitement against the author by the government of Iran. The idea that a state would seek to murder a writer – and an American citizen on American soil – for his creative work should shock and horrify us. So why doesn’t it?

In contrast to the response in France and Britain, where heads of state, the press and leading cultural figures immediately identified the Iranian government’s responsibility for the attack on Rushdie, the American response has been curiously muted.

Mainstream news outlets, including The New Yorker and The New York Times, continue to assert that the motives of Rushdie’s attacker, Hadi Matar, are “unknown.” This is despite the decades-long Iranian campaign to murder Rushdie, and Matar’s own admission and clear evidence that he is a devotee of the supreme leader in Iran and an ardent supporter of Hezbollah.

His profile picture on Facebook is a photograph of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the revolutionary cleric who issued the so-called “fatwa” against Rushdie in 1989. Matar also has a photograph of current Supreme Leader of Iran Ali Khamenei, who has affirmed the death sentence against Rushdie. Even Matar’s fake New Jersey driver’s license combined the names of the two leading members of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah and the late Imad Mughniyeh, who between them take the prize for the most Americans killed in Lebanon. It should come as no surprise that Matar received Iranian military training and indoctrination when he visited his ancestral Lebanese village of Yaroun, a prominent Hezbollah stronghold on the border with Israel.

None of the readily available evidence of state-sponsored violence seems to have factored into how the American press and the White House are choosing to present the attack on Rushdie, who remains in hospital.

The official framing of the Rushdie attack was first tweeted out by US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, who praised the “first responders” who assisted Rushdie after he was stabbed. Sullivan made no mention of Iran or Hezbollah. Articles in The Washington Post and The Atlantic also praise the “first responders” and share their personal histories and current physical condition – one apparently suffered a cut on his eyelid.

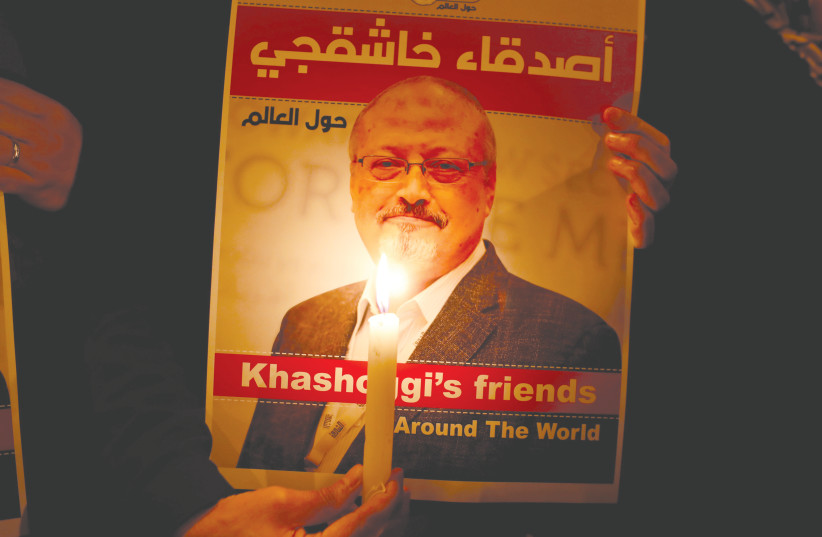

The response to the assault on Rushdie is especially striking when compared to that of the killing of Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi journalist and former government official, who broke with the Saudi government and moved to Washington, where he became a dissident and wrote a column for The Washington Post.

The brutal killing of Khashoggi by agents of the Saudi government was front-page news for many months and continues to be mentioned whenever Saudi Arabia is discussed, and always with the allegation that the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is personally responsible for the murder. After a few weeks of denial, the Saudi government accepted responsibility and arrested and tried the perpetrators. More importantly, the Saudis promised never to engage in extra-judicial and extra-territorial killings again.

The contrast between the two cases begs the question of why Iran’s now successful sponsorship of violence against Rushdie is being glossed over, even though Tehran also recently tried to assassinate several former US government officials who are now under Secret Service protection. The silence is likely because the Biden administration is desperate to re-enter the nuclear deal with Tehran, even as Iran reportedly refuses, as part of the deal, to renounce the prospect of killing US government officials.

One view is that an agreement will also lead to extra Iranian oil barrels and thus a decrease in the price of oil at the pump, which will help the Democrats in the November elections.

Another reason why the perpetrators of the attack on Rushdie are ignored is because he is seen to have offended Muslims and insulted Islam. Khomeini’s false claims about Rushdie are taken at face value and thus he deserves what he gets just as the satirical journalists of Charlie Hebdo also got their comeuppance. This ugly logic, which masquerades as respect for other cultures, is insulting to Muslims because it associates their faith with Iran’s state-sponsored campaign of violence.

And, in fact, a close reading of Rushdie’s books shows that he also had deep appreciation for the beauty and achievements of Islamic civilization – see among other books his The Moor’s Last Sign or The Enchantress of Florence.

Iran’s official response to the recent attack has been to blame Rushdie and claim that he deserved what he got while coyly denying direct involvement. The death sentence is still up on the Internet and praise fills Iranian newspapers for the attempt on the author’s life. In sharp contrast, the Muslim World League’s secretary-general, Sheikh Muhammad al-Issa, called the attack on Rushdie a crime that Islam does not condone. One of the leading Islamic authorities in the world, and a cleric sponsored by Saudi Arabia, condemned the attack as a criminal act, thereby rejecting the weaponization of Islam for political ends.

The difference between the governments in Tehran and Riyadh could not be clearer. Yet because the White House is intent on reviving the nuclear deal, large sections of America’s political and media elites seem bent on erasing reality in favor of a fantasy that a peaceful Iran will emerge after the deal and will be “integrated” with its neighbors. What happened on stage in Chautauqua, New York, should be a warning that deal or no deal the Iranian regime will continue to pursue violent means and use religion for its political ends.

Bernard Haykel, a personal friend of Salman Rushdie, is a professor of Near Eastern Studies and the director of the Institute for Transregional Study of the Contemporary Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia at Princeton University. Mohammed Alyahya, a personal friend of the late Jamal Khashoggi, is a fellow at the Middle East Initiative of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University and a senior fellow at the Center for Middle East Peace and Security at the Hudson Institute.