I write on International Holocaust Remembrance Day – marking the 78th anniversary of the liberation of the death camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, the most brutal extermination camp of the 20th century – about remembrance, and a reminder of horrors too terrible to be believed but not too terrible to have happened.

I write also in the aftermath of the oft-ignored, if it is even known at all, 81st anniversary of the Wannsee Conference of January 20, 1942, convened by the Nazi leadership to address “The Final Solution to the Jewish Question” – the blueprint for the annihilation of European Jewry – which was met by the indifference and inaction of the international bystander community.

We are on the eve also of the 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, begun on April 19, 1943 – the most courageous civilian uprising in all of the Holocaust. There is a straight line between Wannsee and Warsaw; between the indifference of one and the courage of the other.

I write also in the wake of the 78th anniversary of the arrest and disappearance of Raoul Wallenberg on January 17, 1945 – Canada’s first honorary citizen, and an honorary citizen of the US, Australia and Israel. Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat whose leadership and mobilization of other courageous diplomats and Jews was able to rescue some 100,000 Jews in the last six months of 1944 alone – more than any other single government or organization. He demonstrated how one person with the compassion to care and courage to act can confront evil, prevail and transform history.

I write amid the international drumbeat of evil – on the eve of the first anniversary of the unprovoked and criminal Russian invasion and aggression in Ukraine, underpinned by war crimes, crimes against humanity, and incitement to genocide; the increasing assaults by China on the rules-based international order; the Iranian regime’s brutal and massive domestic repression met with the Iranian people’s courageous response of “women, life, freedom”; the mass atrocities targeting the Uyghurs, Rohingya, Afghans and Ethiopians; and the increasing imprisonment of human rights defenders like Russian human rights hero Vladimir Kara-Murza – the embodiment of the struggle for democracy in Russia and the critic of its invasion of Ukraine.

And I write also amid a global resurgence of antisemitic acts, incitement and terror – of antisemitism as the oldest, longest, most enduring, and most dangerous of hatreds; a virus which mutates and metastasizes over time, but which is grounded in one foundational, historical, generic, antisemitic, conspiratorial trope: namely, that Jews, the Jewish people, and Israel are the enemy of all that is good and the embodiment of all that is evil, regardless of what moment in time we are experiencing or living in.

And so, at this important inflection historical moment, we should ask ourselves: What have we learned in the last 78 years – and more importantly – what must we do?

Lesson one: ‘Zachor’ – the danger of forgetting and the imperative of remembrance

The first lesson is the danger of forgetting – the killing of the victims a second time – and the imperative of remembrance, zachor/le devoir de mémoire. As Prof. Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Laureate and Holocaust survivor put it: “The Holocaust was a war against the Jews in which not all victims were Jews, but all Jews were targeted victims.”

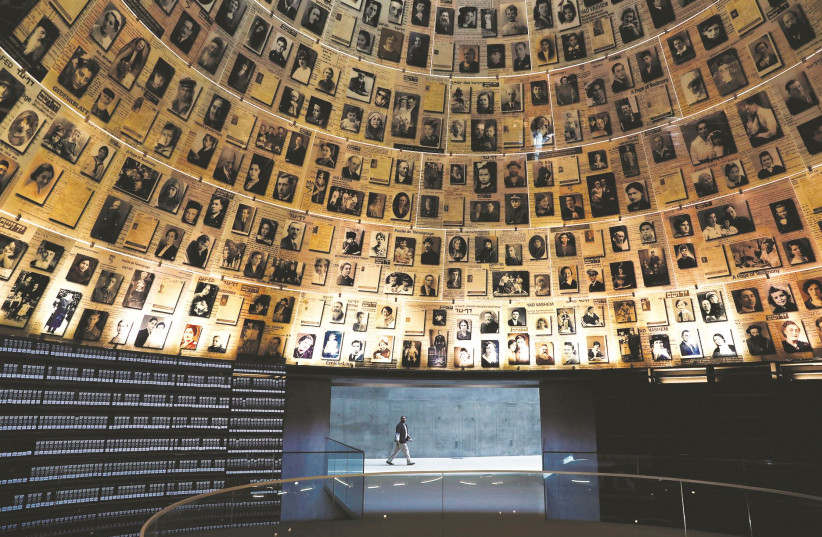

As we remember the victims of the Shoah – defamed, demonized and dehumanized as prologue and justification for genocide – we must understand that the mass murder of six million Jews and millions of non-Jews is not a matter of abstract statistics.

As we say at these moments of remembrance, “Unto each person there is a name, each person is an identity, each person is a universe.” As the Talmud reminds us, “Whoever saves a single life, it is as if he or she has saved an entire universe.”

Just as if you kill a single person, it is as if you have killed an entire universe. Thus, the abiding universal imperative: we are each, wherever we are, the guarantors of each other’s destiny.

Lesson two: The Holocaust as a paradigm for radical evil, and antisemitism as a paradigm for radical hate – learning and acting upon these intersections

The second lesson is the danger of antisemitism – the oldest and most enduring of hatreds – and the most lethal. If the Holocaust is a metaphor for radical evil, antisemitism is a metaphor for radical hate. Approximately 1.3 million people were deported to the death camp Auschwitz, 1.1 million of them were Jews.

Let there be no mistake about it: Jews were murdered at Auschwitz because of antisemitism, but antisemitism itself did not die. It remains the bloody canary in the mineshaft of global evil today. And as we have learned only too painfully and too well, while antisemitism begins with Jews, it doesn’t end with Jews.

As Ahmed Shaheed, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, put it in his landmark report to the UN, antisemitism is “toxic to democracies,” a threat not only to Jews, but to our common humanity. In combating antisemitism, we defend our democracy.

Lesson three: The danger of state-sanctioned incitement to hate and genocide – the responsibility to prevent

The third enduring lesson is that the genocide of European Jewry – like the genocide of the Tutsi in Rwanda, whose 29th anniversary we are approaching, where 10,000 Tutsis were murdered every day for three months – succeeded not only because of the machinery of death, but because of a state-sanctioned ideology of hate.

For example, the Jew was seen as the personification of the devil – as the enemy of humankind – and humanity could only be redeemed by the death of the Jew. As the Canadian Supreme Court affirmed – and as echoed by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda – “the Holocaust did not begin in the gas chambers – it began with words.”

These, as the court put it, are the catastrophic effects of racism. These, as the court put it, are the chilling facts of history. Indeed, in another important principle and precedent, the Supreme Court held that the very incitement to genocide constitutes the crime in and of itself, whether or not acts of genocide follow.

Lesson four: Holocaust denial – from assaultive speech to criminal conspiracy, the responsibility to unmask the bearers of false witness

The fourth enduring lesson concerns the Holocaust denial movement – the cutting edge of antisemitism old and new – which is not just an assault on Jewish memory and human dignity in its accusation that the Holocaust is a hoax. Rather, it constitutes an international criminal conspiracy to cover up the worst crimes in history.

It not only holds that the Holocaust was a hoax, but maligns the Jews for fabricating the hoax, something which is now being repeated in the genocidal denial in Rwanda.

It is our responsibility to unmask the bearers of false witness, to expose the criminality of the deniers as we protect the dignity of their victims.

Lesson five: The proliferation of Holocaust distortion, trivialization, minimization, revisionism and inversion – the responsibility to combat

The fifth enduring lesson concerns the horrifying rise of Holocaust distortion, particularly weaponized by social media. It is a phenomenon that threatens not only our relationship to the truth, but to our collective relationship with history. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic was weaponized, with Jews blamed for manufacturing the virus, and in yet another trope, for profiting from it.

Similarly, a related phenomenon is that of Holocaust trivialization and minimization, where the symbols and imagery of the Holocaust are also weaponized. In Holocaust revisionism, extremist collaborators with the Nazis are glorified as heroes; and in Holocaust inversion, Jews/Israel are compared to Nazis and accused of Nazi-like crimes.

Last year’s adoption of the UN General Assembly Resolution combating Holocaust denial and distortion was as timely as it was necessary.

Lesson six: the danger of silence in the face of evil – the responsibility to protest injustice

The sixth lesson is the danger of complicity by way of silence or inaction. As Wiesel put it in his famed 1986 Nobel Prize address: “We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim; silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented… wherever men or women are persecuted because of their race, religion or political views that place must – at that moment – become the center of the universe.”

He added: “There may be times when we are powerless to prevent injustice, but there must never be a time where we fail to protest against injustice.”

“There may be times when we are powerless to prevent injustice, but there must never be a time where we fail to protest against injustice.”

Elie Wiesel

It is our responsibility, as Wiesel taught us, to speak truth to power and to hold power accountable to truth, as he did so memorably upon receiving the Congressional Medal of Freedom for his efforts.

Lesson seven: Indifference and inaction in the face of mass atrocity and genocide – the responsibility to protect

The seventh painful and poignant lesson is that Holocaust crimes (and genocides such as that of the Tutsis in Rwanda) resulted not only from state-sanctioned incitement to hatred and genocide, but from crimes of indifference and conspiracies of silence, with the international community as a bystander.

What makes the Holocaust and the genocide of the Tutsis so unspeakable are not only the horror of the crimes, but that these crimes were preventable. No one can say that we did not know. We knew, but we did not act.

Today we know, but we have yet to combat the mass atrocities targeting the Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region of China; or the assaults on the Rohingya; or ethnic cleansing in Ethiopia. This ignores the lessons of history and mocks the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine.

Let there be no mistake about it: indifference and inaction always mean coming down on the side of the aggressor, never the victim. In the face of evil, indifference is acquiescence to, if not complicity with, evil itself.

Lesson eight: Combating mass atrocity and the culture of impunity – the responsibility to bring war criminals to justice

The eighth lesson calls on us to combat mass atrocity and the culture of impunity that underpins it.

If the last century, symbolized by the Holocaust and such mass atrocities as the genocide in Rwanda, was the age of atrocity, it was also the age of impunity. Few of the perpetrators were brought to justice. Just as there must be no sanctuary for hate, no refuge for bigotry, there must be no base or sanctuary for these enemies of humankind.

Let there be no mistake about it – indulging impunity only incentivizes mass atrocity.

Lesson nine: Speaking truth to power

The ninth lesson is that the Holocaust was made possible not only because of the “bureaucratization of genocide,” as Robert Lifton put it – and as the Wannsee Conference and the Nazi desk murderer Adolf Eichmann personified – but because of the betrayal of the elites, including scientists and doctors, judges and lawyers, church leaders and educators, engineers and architects.

The Nuremberg crimes were also the crimes of Nuremberg’s elites. It is our responsibility, then, to speak truth to power, to hold power accountable to truth.

The “double entendre” of Nuremberg – of Nuremberg racism and Nuremberg principles – must be part of our learning as it is part of our legacy.

Lesson 10: The assault on the vulnerable and powerless – the responsibility to give voice to the voiceless

The tenth lesson concerns the vulnerability of the powerless and the powerlessness of the vulnerable, as dramatized at Auschwitz by the remnants of shoes and suitcases, crutches and hair of the murdered. Indeed, it is revealing, as Prof. Henry Friedlander points out in his work “The Origins of Nazi Genocide,” among the first groups targeted for killing were the Jewish disabled.

It is our responsibility to give voice to the voiceless and to empower the powerless, be they the disabled, poor, elderly, women victimized by violence, or vulnerable children – the most vulnerable of the vulnerable. The test of a just society is how it treats its most vulnerable among them.

MAY I say a closing word to the survivors, and what I have learned from you. For you have endured the worst of inhumanity, but somehow found in the resources of your own humanity the will to go on, the resilience to build families and relationships, and to make enduring contributions to every community and country you inhabit. We are all your beneficiaries and we will continue to be inspired by your teachings and your example.

And so, together with you, we must remember – and pledge – that never again will we be indifferent to incitement and hate; never again will we be silent in the face of evil; never again will we indulge racism and antisemitism, the most dangerous of hatreds; never again will we ignore the plight of the vulnerable; and never again will we be indifferent in the face of mass atrocity and impunity.

We will speak up and act against racism, against hate, against antisemitism, against mass atrocity, against injustice, and against the crime of crimes whose name we should even shudder to mention – genocide – which you singularly and painfully experienced, and from which we draw the existential lessons of Jewish history and human history.

The writer is an emeritus professor of law at McGill University, International Chair of the Raoul Wallenberg Center for Human Rights, former Minister of Justice and Attorney-General of Canada, longtime parliamentarian, and International Legal Counsel to Prisoners of Conscience. He is Canada’s first Special Envoy for Preserving Holocaust Remembrance and Combatting Antisemitism.