Syria has returned to the family of Arab nations – not as a conquering hero or a popular favorite, but as a factor to be dealt with in the current complex geopolitical repositioning in the Middle East. The 12-year boycott of the Bashar Assad regime has ended; attention will now be focused on the conditions and terms required from it, which, among other things, will include the demand to stop peddling the addictive amphetamine fenethylline, commonly known by the trademark name Captagon, with which it has funded itself until now.

While Syrian opposition and human rights groups protested the immoral nature of rehabilitating Assad’s bloody regime, realpolitik, cynical or not, prevailed. Similar to other matters in the Middle East, in the Syrian issue, too, America’s seeming gradual withdrawal from its previous political and security-related positions has highlighted the creation of new, geopolitical arrangements in the region.

In 2015, then-president Barack Obama’s failure to live up to his previous statement that he would not let Syria cross the “red line” of using chemical weapons against civilians go unpunished, was exacerbated by the Trump Administration’s failure to defend Saudi Arabia’s vital petrol installations – clear negative signs in this regard.

There never is a void in international politics, and America’s diminishing role was filled by Russia and Iran, which despite conflicting economic and other interests joined forces to save the Assad regime. Arab countries that had provided some aid to the rebels before realized that the situation had changed.

How Syria was brought back into the Middle Eastern geopolitical fold

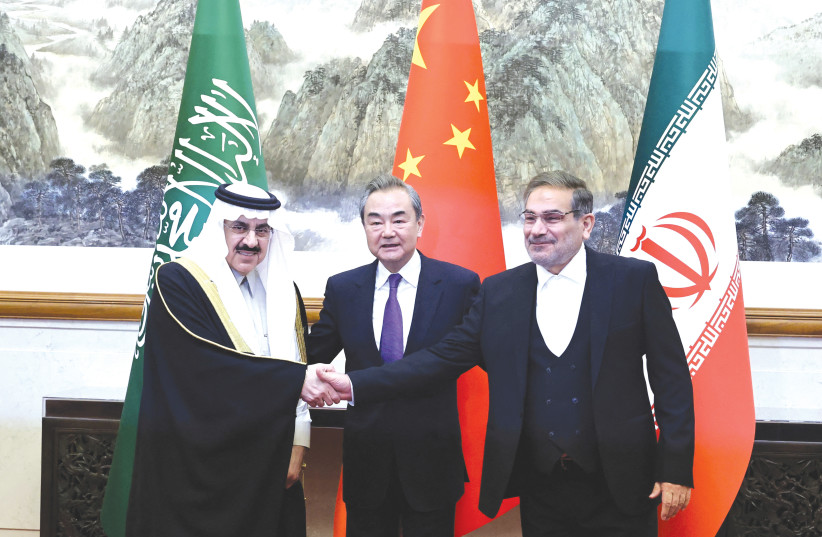

The first initiatives toward Damascus came from the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain as a sort of curtain raiser, getting significantly enhanced when Saudi Arabia took the lead. At the same time, and not in isolation from the Syrian issue, came the Chinese-sponsored normalization between Riyadh and Tehran, which for some reason was met with a shrug by Washington.

As the British Financial Times remarked, the prime factor in these developments was Saudi Arabia’s decision, under the leadership of Crown Prince and de-facto leader Mohammed bin Salman, to “reinvent itself on the stage of world politics,” as a result of what it perceived as the lack of a clear direction in American policy and the diminished trust in the latter’s commitment to protecting its allies.

As a senior Saudi commentator close to the regime commented: “The value of the American security umbrella has been punctured.” Jon Alterman, a senior expert on the Middle East at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, noted that it was indeed “difficult not to wonder what American policy will be in the Middle East in the coming years.”

This is especially pertinent with regard to Iran. While diplomacy, America’s declared aim, is usually preferable in international relations, its chances of succeeding depend on the measure that the parties involved would have something to gain or lose from it. For nuclear-going Iran to proceed with its military bomb and long-range missile plans and other aggressive designs, in the absence of a persuasive United States military option, would be the most logical choice.

As veteran US diplomat and Middle East negotiator, Dennis Ross, said, “They (Iran) are not afraid of us. It’s time to change our rhetoric and make it clear to Iran that its 40-year-old nuclear project is in danger.” The Iranian regime also calculates that it can withstand further economic losses resulting from sanctions, but it has shown in the past that it can be deterred by a credible American show of force – the key word being “credible.”

PRESIDENT Joe Biden did state that the position of the US in the region will remain strong. But the shifting focus of American policy and strategy to the Far East, and later to the Russian front, as well, has raised doubts in the eyes of Middle Eastern diplomats.

Still, Saudi Arabia will strive not to reduce its basic security ties with America or with the American defense industry. Nor has Washington any intention to abandon its special relationship with the House of Saud – despite the strained relations with Riyadh following the Jamal Khashoggi affair and the decrease in oil production by the OPEC countries, led by Saudi Arabia, contrary to Washington’s expressed request. Those positions also have implications for Israel and the potential of its relationship with Saudi Arabia.

Although the latter sees an advantage in furthering its relations with Iran, it has not lost sight of the dangers of Tehran’s nuclear plans and its hegemonic aspirations in the region, nor is the renewed relationship with Damascus intended to strengthen Iran’s standing in Syria, but rather to compete with it and curb it.

One may thus assume that the fact of Arab countries’ turning a page in their relations with Damascus is not necessarily seen also in Tehran as an advantage from its perspective. Actually, the opposite may be true, raising suspicions with regard to Assad’s loyalty to its interests.

Plausibly, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi’s recent visit to Damascus may also have been intended as a preventive move in this respect, i.e. to stop Syria from granting Saudi Arabia and the Emirates an inside track in refurbishing its economy in general, and with its domestic market in particular.

As usual, the rule is “follow the money” and an impoverished Iran cannot compete in this respect with Saudi Arabia and the Emirates. Hence the above’s investments are bound to include certain conditions – and not just purely economic ones. As the Israeli commentator Jacky Hugi wrote: “Syria is a devastated country and needs a broad and comprehensive reconstruction plan. With Syria clearly unable to accomplish this itself, its only option is to rely on foreign funds.

“America won’t come to its aid, nor will Russia, whose economy is groaning under the burden of sanctions and the costs of the war in Ukraine, and nor will Europe, which has its own problems.

“Thus, the restored ties between most of the Arab world and Syria may actually be counterproductive to Iran’s intentions and those of its leaders, who will have to explain to Iranian citizens why channeling tens of billions of dollars to Syria has not benefited them nor alleviated their economic hardships – with someone else reaping the rewards.

“Furthermore, one may assume that Saudi Arabia, and its Arab allies investing resources in the Syrian economy, will want to ensure maximum stability in the country. Iran’s terrorist-supporting activities, the construction on Syrian soil of an aggressive infrastructure by Hezbollah, and other elements aimed at Israel – activities that Israel will obviously continue to oppose by force – go against this aim.”

In this developing situation, Israel, too, will have to play an active diplomatic role, both vis-a-vis the US and the Arab world. The Abraham Accords, initiated by Israel and facilitated by the US, were a significant step not only for Israel (and belatedly recognized by the Biden administration), and the US, but for the entire Middle East.

In this respect, Israel establishing formal ties with Saudi Arabia will continue to be a major diplomatic and strategic goal both for Israel itself and for the US. The latter, despite its problems with Riyadh, still continues to play an active role in this regard, as evidenced, among other things, by the recent meeting between representatives of the Israeli government and two of President Biden’s senior political advisers upon their return from a mission in Riyadh.

Though Saudi Arabia and the Emirates are making common cause on Syria and other matters, this does not necessarily mean that they converge on all other issues, arguably including the Palestinian one.

As a consequence, at least partly so, Saudi Arabia’s apparent hesitancy with regard to normalization with Israel differentiates it from the policy of the UAE, though both recognize Israel’s pivotal role, both politically and eventually militarily, as well in stemming Iran’s ambitions.

The situation in this respect may actually be described more as a potential triangular deal than as an equation – with the US required by Saudi Arabia to respond to certain of its requests – in order for it to agree to normalization with Israel. In this respect too, Israel’s diplomacy can be expected to play an active role.

The writer, a former MK, served as the ambassador to the US from 1990-1993 and 1998-2000.