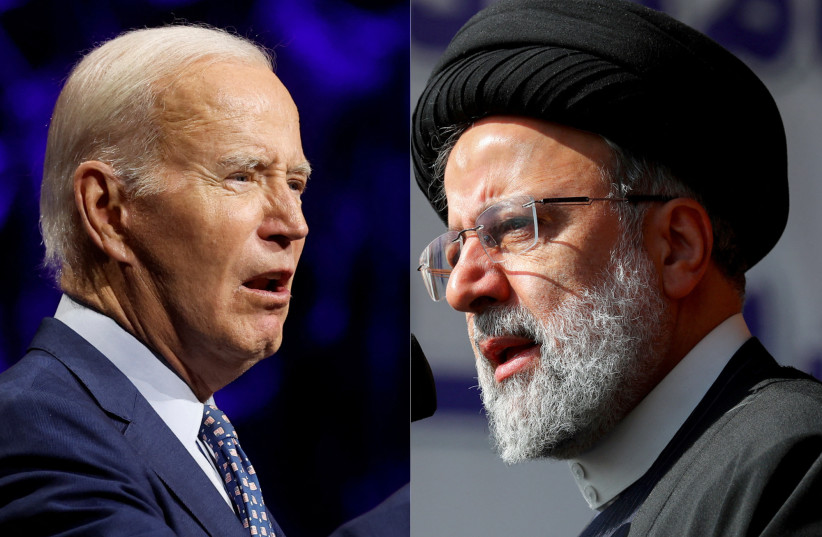

US President Joe Biden served as vice president throughout the presidency of Barack Obama. Sometimes too little significance is given to Biden’s total identification with the major policy initiatives that marked Obama’s two terms in office.

The Iran nuclear deal, endorsed by the UN Security Council in July 2015, was regarded by Obama as one of the crowning achievements of his presidency. His administration masterminded an international agreement between Iran and the permanent members of the Security Council plus Germany. Known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), it removed a raft of sanctions and unfroze and returned to Iran vast sums of money – some $1.7 billion – confiscated during years of sanctions. The quid pro quo was an undertaking by Iran to restrict its nuclear development program and subject it to inspection by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

The Obama administration’s policy was founded on the precarious belief that the Iranian regime would respond to conciliatory gestures, that engaging with it would bring it in out of the cold, and, crucially, that it would honor any commitments it signed up to.

Despite Iran’s unremittingly hostile rhetoric (the US was and remains “the great Satan”), Washington seemed blind to the fact that the Iranian regime had no intention of ever establishing friendly relations with the West. It had, and has, quite different priorities. The Islamic Revolution in Iran was spearheaded by Shia zealots determined to convert Iran into a theocracy, gain political and religious dominance in the Middle East, battle against Western democracy, Zionism, and communism, and establish Islam across the entire world. These ends, in their view, justify the use of any means, which explains the series of worldwide terrorist incidents following the regime’s establishment in 1979, and its continued support for proxy-initiated terrorist activities by bodies such as Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Houthis. In short, the Iranian regime has always been working according to its own agenda, and is hell-bent on gaining a nuclear arsenal to ensure its regional dominance.

Tensions rise as Biden's engagement strategy faces congressional opposition

In April 2015, with the JCPOA deal all tied up and awaiting ratification, Obama was interviewed on America’s National Public Radio.

“My goal,” he said, “when I came into office, was to make sure that Iran did not get a nuclear weapon and thereby trigger a nuclear arms race.... We’re now in a position where Iran has agreed to unprecedented inspections and verifications of its program, providing assurances that it is peaceful in nature.... You have assurances that their stockpile of highly enriched uranium remains in a place where they cannot create a nuclear weapon.”

Despite the clearest evidence that Iran’s hostility toward the US was unshakable, Obama and his team never abandoned their belief in the policy of engagement. The nuclear deal when signed had no effect on the anti-American rhetoric in Iran – if anything, the vitriol increased. In September 2015 Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, tweeted on his English account: “The Iranian nation did expel this Great Satan; we barred their direct access, and now we must not allow their indirect access and infiltration.” And again: “US officials seek negotiation with Iran. Negotiation is a means to infiltrate and impose their wills.”

Donald Trump was skeptical of the JCPOA deal from the start, and during his campaign for the presidency promised on more than one occasion to withdraw the US from it. In May 2018 he did just that.

Biden's attempt to reengage with Iran despite Nuclear concerns

Biden came to the presidency believing as firmly in the policy of engagement with Iran as he had when a key player in the Obama administration. He hoped to rejoin the JCPOA. In September 2019, during his presidential campaign, he wrote: “If Iran returns to strict compliance with the nuclear deal, the United States would rejoin the [JCPOA] agreement as a starting point for follow-on negotiations.”

In point of fact Iran had never been in strict compliance with the nuclear deal, as the secret nuclear archives lifted by Israel in January 2018 from under the regime’s nose demonstrated all too clearly. Irrefutable proof came in February 2023 when IAEA inspectors found uranium particles in Iran’s underground Fordow nuclear site enriched up to 83.7% – very nearly weapons-grade.

Now even Biden acknowledges that the JCPOA is dead. But faithful as ever to the Obama engagement philosophy, and despite every indication that the Iranian regime is not be trusted, his administration is in the process of finalizing an arrangement with it. The Washington Post reports that under the negotiated agreement, payments owed to the Islamic Republic that have long been frozen by sanctions will be released. For its part, in addition to limiting its uranium-enrichment levels and cooperating more fully with the IAEA, Iran has agreed to free three wrongfully imprisoned Americans. The ransom for the hostages may be in the region of $10b., released in the form of sanctions waivers. In addition the US is offering Iran the opportunity to export more oil.

Unveiling what Biden's controversial Iranian non-deal means for diplomacy

However, a huge political hazard lies in Biden’s path. It all turns on the word “deal.” If what Biden is engaged in can be described as a deal, then Congress has the right to intervene – and Biden and his officials know that, if submitted to legislative oversight, any agreement with Iran would meet substantial bipartisan opposition.

The problem arises because Obama negotiated and signed the JCPOA deal using the executive power granted to presidents under the Constitution to enter into agreements with other countries. However, by default or design, he overlooked the essential qualifying clause “by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.” Members of both Houses and of both major parties were outraged, and in May 2015 Congress passed the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act. Gaining overwhelming majorities in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, it gave Congress the right to review any nuclear agreement reached in talks with Iran.

INARA obliges the president to present before Congress any new or amended deal pertaining to Iran’s nuclear program. The lawmakers would then have a 30-day review period and the opportunity to vote it down. A few weeks ago, the Biden administration reassured Congress that it would abide by its provisions and submit any new deal with Iran for review and approval.

This is why “deal” has become a dirty word in Washington. “Rumors about a nuclear deal, interim or otherwise, are false and misleading,” State Department spokesman Matthew Miller told journalists in June. In briefings with journalists, officials now use expressions like “mini-agreement” and “interim arrangement.” So whatever the understanding or bargain is between Biden and Khamenei, it is certainly not a deal.

The writer is the Middle East correspondent for Eurasia Review. His latest book is Trump and the Holy Land: 2016-2020. Follow him at: www.a-mid-east-journal.blogspot.com.