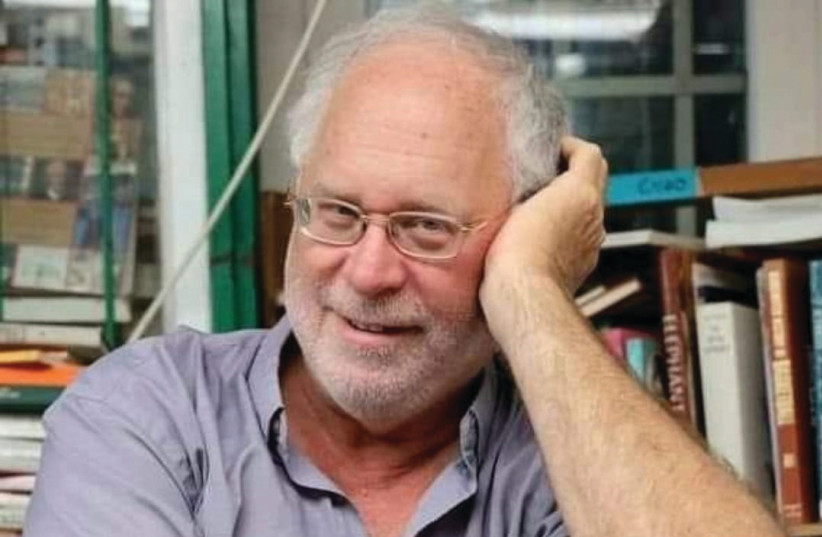

In his cluttered studio in Ashdod, Hananya Goodman sits in front of a canvas, with the lulav (palm branch), drenched in deep black ink in his hand.

After many thin incoherent brush strokes, splatters, whacking, and waving, he has a “voice inside telling him: Stop this piece.”

You’d think this would be the work of a child in kindergarten. But there’s much more to it than that.

This particular lulav, he says, is called Sarah, and he’s created over 20,000 pieces with its help as a tool.

He says he considers “each image as a character, both in a personal identity sense, and in an ideographic sense. The images created have now taken on a life of their own. They live with me and one another, in a sense.”

Have you ever imagined what it would be like to create your own personal, self-contained, complex language?

The language Hananya is creating, is in fact part of a larger recent phenomenon in the communications and art world, called “asemic writing”.

Since the end of the last millennium, this hybrid modality between text and image has been slowly spreading and growing around the world. It has existed long before there was a name for it, but visual poets Tim Gaze and Jim Leftwich dubbed it so after the term “asemia”.

If “seme” is the smallest unit of meaning, then “asemia” is the loss or inability to comprehend that meaning in any form or way, in both a literal, and a psychophysical manner. Words, gestures, language, symbols, and signs – it is the void in which those things carry no weight.

Asemic writing then, on the surface, is a language with no conveyed meaning or coherence.

At this point, most knowledgeable viewers would put down the work of art, exclaiming that if it lacks inherent meaning, it lacks inherent value. Information over effect. Understanding over existence. Asemic writing is the antithesis of that, which, in turn, gives it value. The lack of meaning creates meaning. Goodman prefers the term “prosemic”, tending toward meaning.

Asemic writing actually delves deep into our subconscious universes, and we can draw parallels from our grasp of the idea to many aspects of our lives. “We are surrounded by scripts we do not understand and the brain knows they have meaning because they appear “as if language like” and this “as if language” is the same experience “as looking at asemic writings,” Goodman says.

THE PROCESS of writing is the same as the process of imaginal thought itself. Our movements are always in a forward inclination, conceptualizing thoughts down onto paper. It is when we see these movements past the habitual face value we’ve given alphabetical coherent writing, rendering it only as a tool to transcript something else, and give emphasis to the writing itself, that we can see the value of asemic.

The Finnish Satu Kaikkonen says “For all its limping-functionality, semantic language all too often divides and asymmetrically empowers, while asemic texts can’t help but put people of all literacy levels and identities on equal footing. Asemic art… represents a kind of language that’s universal and lodged deep within our unconscious minds.

“Regardless of language identity, each human’s initial attempts to create written language look very similar and, often, quite asemic. In this way, asemic art can serve as a sort of common language – albeit an abstract, post-literate one – that we can use to understand one another.”

To globally unite within our individual differences under one post-literate language sort of sounds like what we do on Sukkot.

As suggested by Lurianistic Kabbalah and hassidism, to wave the Four Species in all directions with a repeated movement to the heart, represents us all. We receive divine energies from the six sefirot above Malchut, shown by each direction. Each species being a different combination of taste and smell, in turn representing four types of people that make up Judaism in our nation. We are then united as a people by the process and the gestures by which we visually communicate with God.

A rich Jewish history of experimenting with language

ONE OF asemic writing’s predecessors, among other streams, like concrete poetry, xenolinguistics (the 2016 movie Arrival might be familiar to some), and psychography, is the Dadaist movement of Lettrism, which was founded by Isidore Isou in 1940’s Paris.

Both Lettrism and Asemic are based on the goals of infringing on the status quo and circumventing meaning. They often operate on the fringes of the mainstream due to their bizarre tendencies, although they are deeply affected by Kabbalist mysticism, namely, Abraham ben Samuel Abulafia, the 13th-century Spanish founder of prophetic Kabbalah, and his Kabbalah of Names.

Abulafia had studied and taken on board the ideas of the Book of Creation, and the holiness of the Hebrew language being the source of the creation of the world within its letters, consonants, and names, designating them as symbols of existence.

To Abulafia, the Hebrew language is a tool of God to create the world, and we, as humans, can attempt to reverse-engineer it in order to reach unitive and revelatory experience, and figure out the secrets of the world.

One such process is Tzeruf Otiot, deconstructing names into the “atoms of reality,” the letters finding their primordial essence, and reforming them into the “root of God”. God’s name is buried deep beneath the surface world, the one we take for granted, but is always present, and Abulafia’s meditations focus on uniting and communicating with God through recitations of divine names.

Connecting with the likeminded around the world

Goodman, who made aliyah from Racine Wisconsin, says he started Asemic “after decades of writing down and scribbling my meaningful thoughts on paper. About four years ago at the age of 66, I started to scribble but without writing the words, just the gestures and motions and then I started to dance around the page.”

As far as I know, he is the only person in the world to be using a lulav to paint or write, and started using it because of a “need to identify new tools for creating Asemic writing and new characters”

The closest analogy in Jewish tradition to using the lulav as a writing instrument is the Hyssop plant, Ezov, with which the Hebrews were told to mark their doorposts using lamb’s blood in Egypt.

He says the Lulav “offers little control and therefore is a poor candidate for writing scripts that need a basic level of control to repeat a pattern,” however, it is perfect for his Asemic writing, which seeks repeatedly to discover the beauty and pleasure of chance and order.

There are many people around the world developing their own personal Asemic languages. These efforts are a testament to the desire to transcend the limitations of available languages and find a common humanity, and at the same time, freely expand the possibilities of meaning.

Understanding our connection to meaning, lack thereof, language, names, and divinity could be the basis of uniting us as denizens of the world, and as a people.

For now, Goodman is just happy with making art: “Showing art has connected me with a community of like-hearted and like-minded artists and followers around the world. I am grateful for their friendship, and my images are glad to participate in this larger world. Every day is full of animation and discovery and recognition. It is a huge pleasure to have some control and fluency or flow over something in my life. Most of my life has been serving others to the best of my ability. I submitted to their control. Today I am doing something very personal and subjective that gives me pleasure.”

You can find thousands of Goodman’s pieces on his Facebook page www.facebook.com/hananya.goodman/photos