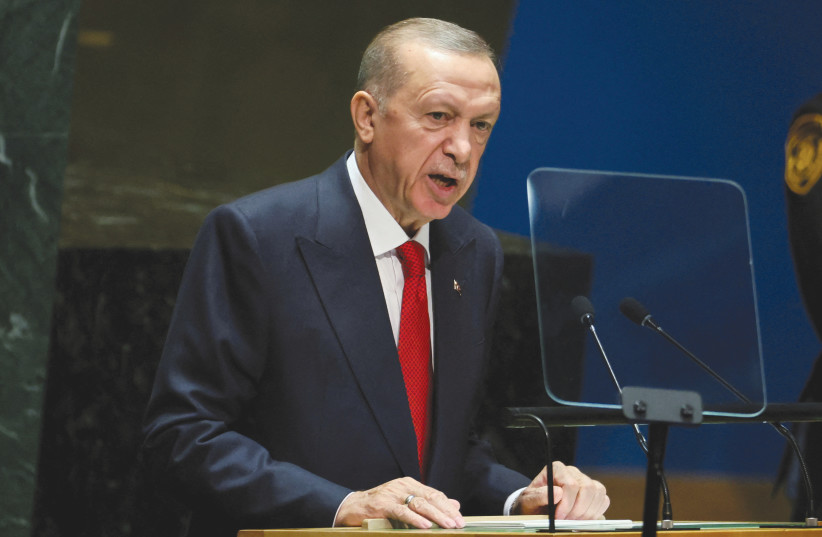

Ever since Recep Tayyip Erdogan gained power as Turkey’s prime minister in 2003, Turco-Israeli relations have been on a see-saw, now up, now down – although more often down than up. This is scarcely surprising since Erdogan is a deeply committed devotee of the Muslim Brotherhood, an organization whose DNA is imbued with antagonism towards Jews. However, he is also a consummate politician, well aware of the need, from time to time, to temper his aversion to Israel with sweet words and conciliatory gestures.

On December 27, Erdogan announced to the world that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was Adolf Hitler reborn, comparing Israel’s campaign to destroy Hamas in Gaza to the systematic annihilation of the Jewish people by the Nazis. In a speech at an event in Ankara, he addressed an absent Netanyahu: “How are you any different from Hitler?” adding, to rapturous applause: “What Netanyahu is doing is no less than what Hitler did.”

A riposte was readily to hand. Netanyahu resorted to the social media platform X (formerly Twitter) and accused Erdogan, with some justification, of carrying out “genocide against the Kurds.” Erdogan, he wrote, “is the last one to give us a lesson in morals... He holds the world record of imprisoning journalists who object to his regime.”

Anyone familiar with the to and fro of interchanges between Ankara and Jerusalem would have experienced a feeling of déjà vu.

This particular exchange of insults was nothing new. In July 2028, roundly condemning Israel’s just-passed Nation-State Bill, Erdogan asserted: “Hitler’s spirit has re-emerged in some Israeli leaders.” Netanyahu’s response? “Erdogan is slaughtering Syrians and Kurds and imprisoning tens of thousands of his fellow citizens,” adding, “Turkey is becoming a dark dictatorship under Erdogan.”

During his early years as prime minister, Erdogan was careful not to promote too radical an agenda too soon. Despite his Islamist views, he made an official visit to Israel in 2005 to be feted by Israel’s then-prime minister, Ariel Sharon. However, it was not long before the previously close relations between Turkey and Israel began to sour. The turning point came in 2009 with the first conflict between Israel and Hamas, which had seized power in the Gaza Strip and had been firing rockets indiscriminately into Israel.

In the annual international gathering at Davos that year, Erdogan could not restrain himself. Rounding on Israeli president Shimon Peres, Erdogan called the Israeli operation in the Gaza Strip a “crime against humanity” and “barbaric.” Wagging his finger at Peres, he declared: “When it comes to killing, you know very well how to kill. I know very well how you hit and killed children on beaches.” Then, infuriated by the moderator’s refusal to allow him more time to respond to Peres’s emotional rebuke, he stalked off the stage.

What followed was the great barren waste of the Mavi Marmara affair. On May 31, 2010, an encounter on the high seas between Israeli soldiers and a Turkish flotilla nominally on a humanitarian mission to Gaza ended with the loss of life of nine of those on board the leading vessel. Erdogan manipulated the event into a rupture of Turkish-Israeli relations lasting six years. The affair was only finally put to rest in June 2016.

When on May 14, 2018, then-US president Donald Trump implemented his intention to relocate the United States Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, Erdogan declared three days of national mourning. The next day, Turkey expelled the Israeli ambassador and withdrew its ambassador from Tel Aviv. In response, Israel expelled Turkey’s consul in Jerusalem.

The next two years saw Turkey’s international standing slump to a new low. By the autumn of 2020, Erdogan was in the process of purchasing the Russian S-400 anti-aircraft system, designed specifically to destroy aircraft like the US’s state-of-the-art multi-purpose F-35 fighter. Reasonably enough, Trump refused to allow Turkey, a member of NATO, to acquire it, ejecting Erdogan from the F-35 program and imposing sanctions on Turkey.

The EU also sanctioned Turkey. In this case, it was in reaction to Erdogan continuing to explore gas in what is internationally recognized as Cypriot waters. The UK, now no longer in the EU, imposed sanctions on Turkey on the same grounds.

Turkey’s relations with Egypt had been frozen solid ever since 2013 when Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi was ousted by Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Erdogan expelled Egypt’s ambassador, and Sisi reciprocated. Relations with Saudi Arabia had been overshadowed for years by the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

As for Israel, it had long been obvious that Erdogan seized every opportunity to denounce Israel in the most extravagant terms and to act against it whenever he could. Not the least of his hostile moves was to support Hamas and to provide a base in Istanbul for senior Hamas officials, granting Turkish citizenship to at least 12 of them.

In short, Turkey, in pursuit of its own political priorities, had fences to mend with, inter alia, the US, the EU, the UK, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Israel.

This was the background to Erdogan’s sudden and dramatic change of tone on the international stage. Erdogan, or his advisers, must have realized that to achieve his strategic objective of extending and stabilizing Turkey’s power base across the Middle East, a fundamental reassessment of tactics was called for. Out of what must have been a root and branch analysis came a plan to address the problem – Turkey would embark on a charm offensive involving “reconciliation” or “rebooting” of relationships with one-time enemies, opponents, or unfriendly states.

Accordingly, Erdogan set about making conciliatory overtures to Germany, the EU, Saudi Arabia, and even Greece. Israel, too, received indications that a rapprochement was sought and – doubtless despite misgivings – on March 9, 2022, President Isaac Herzog became the first Israeli president to visit Turkey in 15 years.

In an interview on Turkish TV at the time, Erdogan said: “This visit could open a new chapter in relations between Turkey and Israel,” adding that he was “ready to take steps in Israel’s direction in all areas.”

The new chapter lasted about 18 months.

By October 25, Erdogan was praising Hamas as “liberators” and condemning what he described as “the Israeli regime’s unlawful and unrestrained attacks against civilians.”

By January 2024, he was backing South Africa’s genocide claim against Israel in the International Court of Justice. In short, Erdogan had reverted to his default mode.

The writer is the Middle East correspondent for Eurasia Review. His latest book is Trump and the Holy Land: 2016-2020. Follow him at: a-mid-east-journal.blogspot.com.