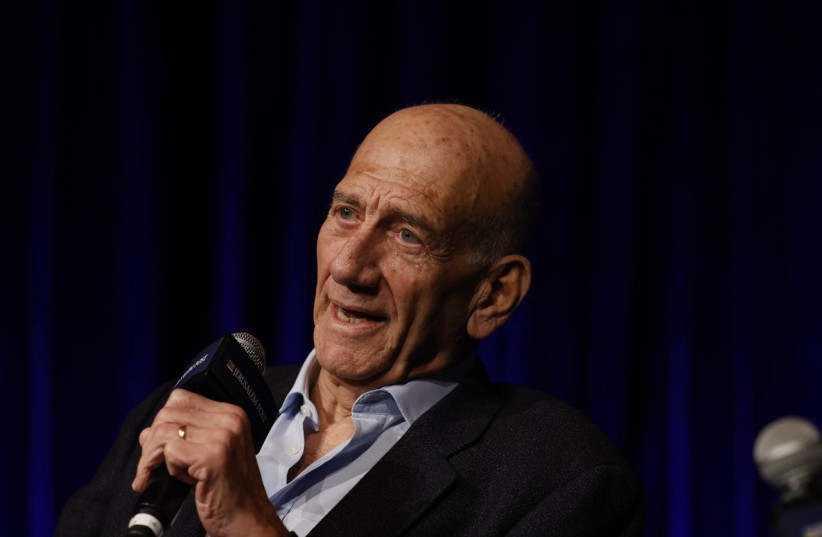

On July 13, 2007, then-US president George W. Bush placed a phone call from the Oval Office to Jerusalem. He was looking for Israel’s prime minister at the time, Ehud Olmert.

Months earlier, Israel had brought intelligence to the Americans about a nuclear reactor that North Korea was building in northeastern Syria. Olmert had asked Bush to attack and destroy it, and, after months of deliberations, the president was calling to inform the prime minister of his decision.

“I cannot justify an attack on a sovereign nation unless my intelligence agencies stand up and say it’s a weapons program,” the president told the Israeli premier. Instead, he said, he would be taking the issue to the International Atomic Energy Agency and then to the United Nations.

At first, Olmert listened, but when Bush was done speaking, his response was forceful and immediate.

“Mr. President,” he started. “I understand your reasoning and your arguments but don’t forget that the ultimate responsibility for the security of the State of Israel rests on my shoulders, and I’ll do what needs to be done, and trust me – I will destroy the atomic reactor.”

It was a moment that could have led to a great crisis between Israel and the United States, especially at a time when the IDF feared that the bombing of the reactor could lead to an all-out regional war with Syria and Hezbollah. But it didn’t. Bush respected Olmert’s forceful stance, and while he disagreed with the decision, he ordered his staff not to get in Israel’s way.

The similarities between then and now

I’ve been thinking a lot about the Olmert-Bush phone call ever since Sunday morning and after Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had his own phone call with President Joe Biden following the Iranian missile and drone assault against Israel.

Both are instances of presidents trying to persuade a prime minister of a policy with which the Israeli leader disagrees, and in both cases, the prime minister pushed back.

There was a similar tension with the Americans in 1981 when then-prime minister Menachem Begin decided to take unilateral action against the Osirak nuclear reactor Saddam Hussein was building near Baghdad.

Then-president Ronald Reagan was adamantly opposed to Israeli action, and while the US allowed a sharply worded resolution to pass at the Security Council, Reagan said that he would not publicly condemn Israel. “That would be an invitation for the Arabs to attack,” he said at the time.

Osirak and Syria were two cases separated by 26 years but connected by a similar foundation: an understanding in Jerusalem that even at the risk of deteriorating ties with the United States, Israel needs to do what is right for the security of its people. America might not like it, but as seen in these two cases of existential threats, the crisis is averted when explained with conviction.

The reason the crisis was averted was because there was a strong foundation of respect between the governments, something that is sadly missing today to the blame of both sides. The Biden administration came into office with a distrust of Netanyahu and made it very clear that it did not want him reelected. When he returned to office at the end of 2022, the White House again made clear its distrust of Netanyahu, his coalition partners, and their policies.

Looking back at last year

It might seem like a lifetime ago, but think back to last year, when it was questionable if Netanyahu would even get a meeting with Biden on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York. Being invited to the White House, a given under past presidents and prime ministers, was not even in the cards, and the New York meeting was only finalized days before it took place.

That meeting was on September 20, just 17 days before the October 7 attacks. While the snub of Netanyahu was obviously not what motivated Yahya Sinwar and Mohammed Deif to launch the Oct. 7 attacks, it is hard not to think about what was going through their minds when they saw the tension with the US. If anything, it most certainly didn’t make them consider that they needed to change their plans. On the contrary, if there was a time to attack, it was now.

Israel didn’t exactly help itself either. The judicial reform that ripped the country apart and the constant attacks by Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich against Biden, as well as Netanyahu’s refusal to rein them in, did not help foster trust. In the end, as one Washington insider explained to me this week, you get what you ask for.

And this is why, after everything, when Iran attacked on Sunday morning, the interception of the missiles and drones was only the first challenge.

The next part was coming up with the appropriate response, which, as of this writing on Thursday afternoon, has yet to take place, while trying to get the Americans on board for whatever might happen next.

On the one hand, it is hard for Israel to retaliate when it does not feel that America is on board. The fear of a wider conflict, particularly with Hezbollah and the potential damage and devastation to the Israeli home front, is hard to think about when knowing that America is not immediately in your corner.

On the other hand, it is almost impossible to imagine an American president sitting on the sidelines as Israel is hit with thousands of missiles from Lebanon and Iran. The president doesn’t have to agree with the decision but it would be hard for him to refuse support like the continued supply of munitions and spare parts so that Israel can fight back.

BEYOND THE NEED to work to restore trust, which might no longer even be possible, the recent and unprecedented attack from Iran underscores something else that Israelis need to keep in mind: The world only likes us when we are under attack or, as author Dara Horn named her brilliant book, “People love dead Jews.”

In the aftermath of October 7, the world united in declaring its support for Israel’s right to defend itself, but the moment the attack was over, it called for restraint. In other words, only when Israel is attacked can it defend itself, but that defense is exactly that: a defense, not an offense.

This is a mistake that emboldens Iran, Hamas, and Hezbollah. It is an exact repeat of what happened in Gaza: Israel was attacked in an unprecedented way, but when it responded with a ground offensive, it was immediately told to stop.

Isn’t it time for a change?

The writer is a senior fellow at the Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI) and a former editor-in-chief of The Jerusalem Post.