Buck O’Neil, one of the greatest players of the Negro League and the first African American coach in the majors, reminisced to Ken Burns and Geoffry Ward in the epic documentary Baseball about that deep sound the bat makes when a home run is hit. After talking about hearing the unique sound Babe Ruth and Josh Gibson made when their bats made contact with the ball, he said, “I heard this sound one more time that I had heard only twice in my life. Now, you know who this is? Bo Jackson swinging that bat. And now I heard this sound… And it was just a thrill for me. I said, here it is again. I only heard it three times in my life.”

As exciting as home runs are — baseball is more than just home runs and baseball is more than just a game — baseball is also a metaphor of life played before our eyes in the infield and outfield. Every batter stands at home plate hoping to return there, following their journey around the infield. They are Odysseus, the Prodigal Son, the Children of Israel making their way back home. Obstacles often must be overcome in such adventures; with baseball, that reality exists every time the batter stands in the batter’s box facing the pitcher.

In baseball, when one is up to bat, when one is on offense the other team has the ball! Not only that: The average pitcher throws the ball at the batter at around 92 mph. Those facets of baseball make it unique in sports and also serve as the perfect allegory for life. We may like to be in control or feel we are in control, but life constantly lobs things our way.

This offense/defense paradox of batting in baseball is why a good batting average is .300, meaning that a good baseball player fails 70% of the time. Calling that a failure misses the important nuance of not getting on base. Batters carry all their previous batting experiences with them each time they step into the batter’s box, where successes as well as failures carry and teach important lessons. That is true for us as well.

I WAS 11 when I attended my first major league baseball game with my family on June 19, 1969. The Mets beat the Phillies 6-5 at the old Connie Mack Stadium. Art Shamsky went four-for-four, including two home runs, and pitcher Tom Seaver stole second base. Those ‘Amazin Mets would go on to win the World Series, having started the season at 100:1 odds against that being possible. The excitement and magic of that baseball season sealed a lifelong love of the game. Over the decades, most of the games I’ve attended have been with family members. My mother-in-law loves to score the game on an official scorecard, and so we make sure to get one for her when we arrive at the stadium.

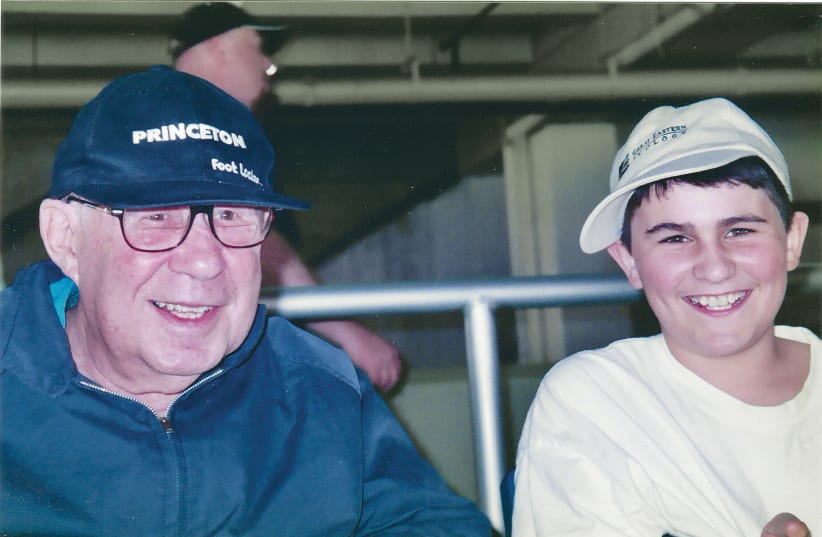

One of my parents’ first dates was to a baseball game in New York. For the last 17 years of my father’s life, he lived with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a disease similar to Parkinson’s disease. As his PSP became more acute, and mom had to take greater care of him, the physical manifestations of the disease became more pronounced, including a less expressive face.

However, there were two moments when baseball changed that. The first was on April 27, 2003, when, along with my son we witnessed Kevin Millwood pitch a no-hitter against Barry Bonds and the San Francisco Giants. As soon as Millwood threw the final pitch, I turned to my father and said, “We just saw a no-hitter.” At that moment, his face lit up in a joyous smile — a rarity with his PSP. For his birthday the next year, we went to Yankee Stadium to see the Yankees play the Kansas City Royals. Between the top and the bottom of the sixth inning we were able to arrange for the scoreboard to say “Happy Birthday Al Cohen.” Once again, that smile returned.

My father fell a lot because of the PSP. Despite the pain and bruises, I never heard him complain once about those indignities. His favorite songs was “Pick Yourself Up” (music by Jerome Kern and lyrics by Dorothy Fields), made popular originally by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in 1936 in the movie Swing Time.

Nothing’s impossible, I have found,

For when my chin is on the ground,

I pick myself up, dust myself off,

Start all over again.

Related, Buck O’Neil also said, “I think sports in general teach a guy humility. I can see a guy hit the ball out of the ballpark, or a grand slam home run to win a baseball game, and that same guy can come up tomorrow in that situation and miss the ball and lose the game... But one thing about it though, you know there will always be tomorrow. You got me today, but I’m coming back.”

Leo Durocher said, “Baseball is like church. Many attend, few understand.” To put that another way, we all experience life on many levels — from the simple through the sophisticated. The beauty of baseball is that it can be a rich experience at all levels, making it a very democratic and all-embracing national pastime. ★

The writer is rabbi emeritus of the Israel Congregation, Manchester Center, Vermont, and a faculty member of the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies and Bennington College.