The Talmudic maxim: “He who desires to acquire knowledge should turn to the south” (Baba Batra 25b) no longer rings true, at least not concerning the study of the Bible. Ben-Gurion University of the Negev has closed its Department of Bible, as of this new academic year. Because there was no formal announcement by the university of this closure, I found it hard to believe the rumor that at the institution that proudly bears the name of the person who personified the centrality of the Bible in our lives perhaps more than any other public figure in the history of the State of Israel, Bible would no longer be taught. Therefore, I checked the course catalog on the university website and I discovered that it was true: Bible studies had been deleted from the Student Handbook for 5782.

For me personally, the closing of the Department of Bible is especially sad. Almost a jubilee ago, in September 1972, on the completion of my doctorate, I arrived in Beersheba and the University of the Negev (later to become Ben-Gurion University of the Negev), together with the handful of other lecturers who had been mobilized to establish the Faculty of Humanities. Two years later, I was asked to undertake responsibility for biblical studies, and, for the next decade, I served as chairman of the Department of Bible. In those years, classes were full to overflowing with students who came from all parts of the Negev, eager to study humanities, and especially Bible and the history of Israel in the biblical period.

But this high watermark of the 70s and 80s was followed by an extended low tide, and like many other areas of humanistic study, a large drop in student registration hit the Department of Bible. Even at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem to where I moved in the early 90s, classes emptied out. Indeed, all of Israel’s universities wrestled with a similar crisis: David and Solomon, Isaiah and Jeremiah no longer interested the hi-tech generation. There are many reasons for this sea change and this is not the place to discourse on the decline of the interest in the study of the Bible, but the solutions that other institutions found for this problem are pertinent.

Take, for example, Tel Aviv University. Several decades ago the university decided to combine its small Department of Bible with other fields of study that were on the verge of closure in a new unit: Hebrew Culture; in this way, the Bible was saved from the sword. Of interest, is that two years ago, the Department of Bible was resuscitated in Tel Aviv as an independent department. A different combination was created at the University of Haifa so that today the Bible is studied together with the History of Israel (that includes the biblical period). It is clear that these two institutions understood that the study of the Bible, the foundation stone of Israel’s culture, cannot be forfeited under any circumstances.

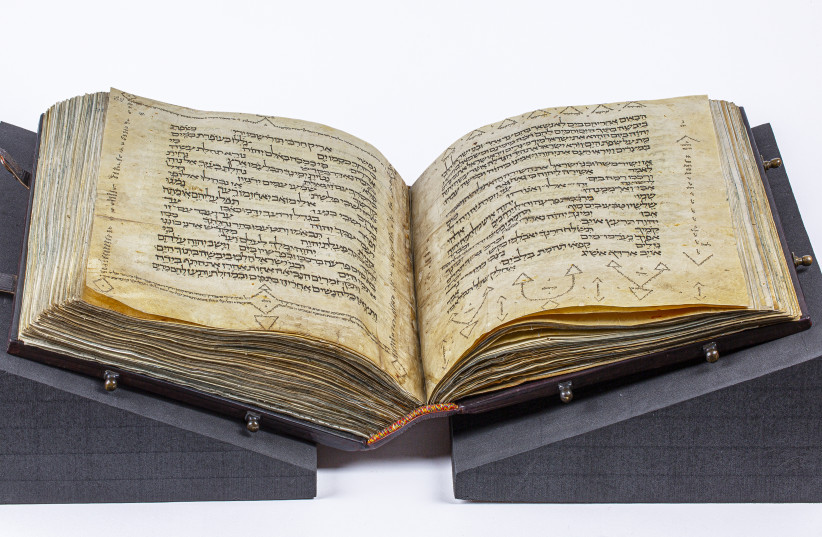

David Ben-Gurion put it this way: “In all the wanderings of the Jewish Diaspora over hundreds of years, the Book of Books accompanied it, including the good tidings of redemption and the return to Zion, the tidings of the flowering of the desert and the ingathering of the exiles... But not only did the Jewish people derive knowledge of their past and hope for their future from the Book of Books. The Bible bequeathed to our people, and through it to all humanity… sublime humane values, the value of human brotherhood, the values of justice and righteousness, truth and kindness, the equality of nations and peace that are the essence of prophetic teaching and the morality of Judaism” (David Ben-Gurion, Iyyunim baTanakh [Tel Aviv 1976], p. 221).

The decision of the administration of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev to close the Department of Bible was taken in the back rooms in blatant disregard for accepted academic procedures, without consultation with the Department of Bible and the Assembly of the Faculty of Humanities. Keeping it under wraps until now points to its problematic nature. Perhaps those who decided on this move thought that in this manner they could minimize the embarrassment brought on the university by their decision – forfeiting national and universal cultural treasures inherent in “the eternal Book of Books” that the Jewish people gave to the world (as proclaimed in Israel’s Declaration of Independence). The decision to close the Department of Bible resembles the behavior of thieves in the night; public discussion in the light of day will hopefully expose its wrongheadedness and open a window for correction.

The writer is a professor emeritus in the Department of Jewish History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.