Sitting in the Knesset recently at the preliminary hearing about the new conversion bill, I was struck by the positive attitude and resilience of the people around the table.

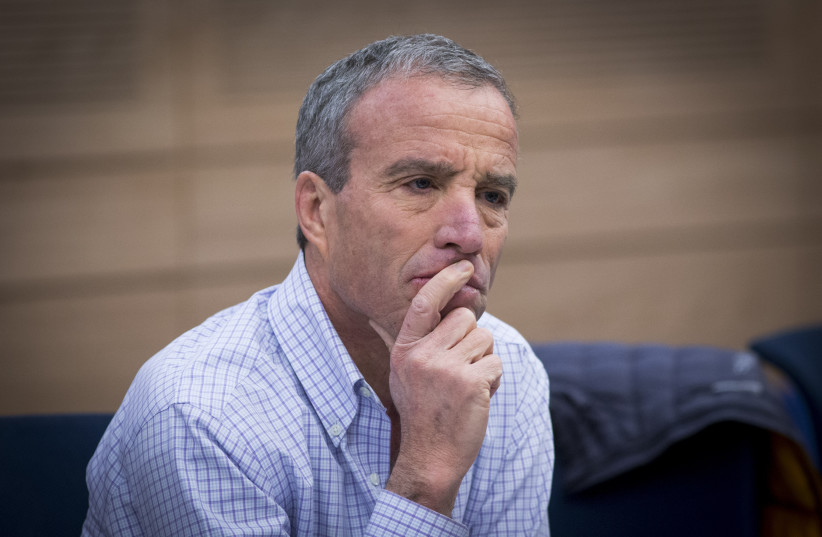

Intelligence Minister Elazar Stern was the one who originally tabled the proposed bill in 2013 in an effort to encourage immigrants who are registered in the population registry as “no religion” to pursue conversion. He was also instrumental in ensuring that the bill was part of the coalition agreements.

Today’s conversion authority is controlled by the chief rabbi and some 30 rabbinical court judges who exclusively control the right to convert. For years, activists and politicians have been trying to pass legislation that would enable more rabbis to engage in conversion, and until now, with little success. “If we were to do nothing else save pass this law,” said Stern to the committee, “it would justify the creation of this government.” Stern has been talking like this for at least 15 years, and it is inspiring that he hasn’t given up.

MK Gilad Kariv was a member of the Neeman commission in 2000 and helped draft its recommendations on conversion then. Though he himself is a Reform rabbi, he argued at last month’s meeting that changing the way Orthodox conversion is done in Israel could make a difference. And this, despite the fact that since the Neeman Commission submitted its report, the number of “no religion” Jews has gone up to 450,000. It is inspiring that he hasn’t given up.

And MK Yulia Malinovsky, a Russian immigrant who served on the Holon City Council in 2003 before becoming an MK has become an unlikely champion of conversion rights. She herself is secular, and the child of a Jewish mother and a non-Jewish father. During the committee meeting, she spoke passionately about improving the chances for immigrants to go through halachic conversions that will be recognized for purposes of marriage and divorce in Israel. She is working with Religious Services Minister Matan Kahana to pass the bill.

Unlike tens of thousands of immigrants who have lost hope of converting or were discouraged from converting by a laborious process, I believe, together with those at the table, that there is still a chance to enable those who want to convert to do so in an embracing way.

And from my perspective, there is no reason to give up. Though the Conversion Authority is in crisis – spending more than NIS 60 million a year and converting fewer than 2,000 people – private conversions, particularly Orthodox ones, are on the rise. There is good reason to believe that should the new legislation pass, immigrants who are seeking conversion – particularly for their children – will have a new avenue that is transparent, straightforward and simple to convert to Judaism.

This is particularly true for those with a long view of Jewish life in Israel. An emphasis should be placed on converting young families, and particularly young children. The halachic requirements to convert children are significantly different than those of converting adults, and this provides a window to enable thousands of families to reconsider taking this step toward mainstream Jewish society in Israel. The resilience of Israel’s policymakers on the conversion issue is remarkable. It is up to us to ensure that those who are interested in conversion don’t give up.

The writer, a rabbi, is director of ITIM and founder of ITIM’s Giyur K’halacha conversion courts.