Iran, uranium and Israel’s stakes in Kazakhstan’s leadership transition

The astute Kazakh president is likely to strike a careful balance between the interests of Jerusalem and Tehran.

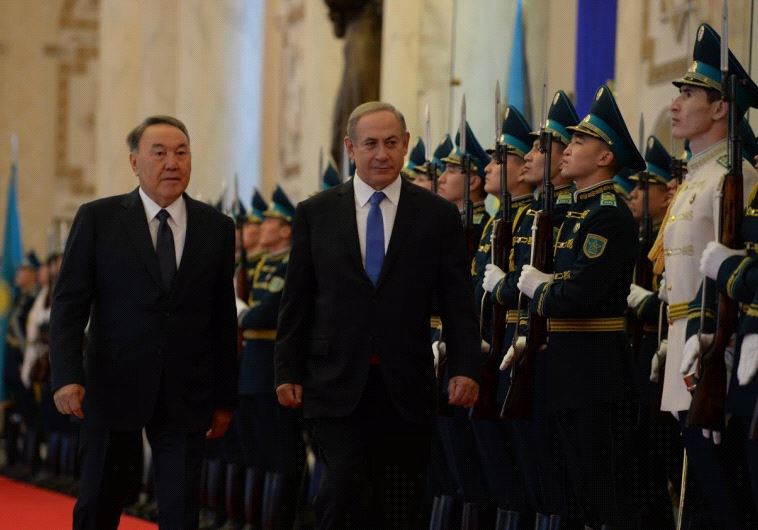

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu with Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev(photo credit: CHAIM TZACH/GPO)

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu with Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev(photo credit: CHAIM TZACH/GPO)