In a warm and humid Jurassic Period landscape lush with plant and animal life in what is now southwest Montana, an adolescent long-necked dinosaur was miserably sick with flu and pneumonia-like symptoms - probably feverish and lethargic with labored breathing, coughing, sneezing and diarrhea.

Some 150 million years later, the skeletal remains of that unfortunate beast, nicknamed "Dolly," represent the first-known dinosaur with evidence of respiratory illness - abnormal growths resembling fossilized broccoli on three neck bones that formed in response to an infection in air sacs linked to its lungs.

Scientists said on Thursday the dinosaur appears to have suffered from a fungal infection similar to aspergillosis, a common respiratory illness often fatal to modern birds and reptiles that sometimes causes bone infections. The condition may have killed Dolly, they said.

Dinosaurs suffered from maladies just like any other animals, but evidence is scarce in the fossil record because soft tissue rarely is preserved in a fossilization process that favors hard stuff like bone, teeth and claws. Dinosaur fossils previously have shown pathologies such as broken and healed bones, tooth abscesses, blood-borne infections affecting bone, arthritis and even bone cancer.

Dolly belonged to a previously unknown species of sauropod dinosaur, a plant-eating group with long necks, long tails, small heads and four sturdy legs that included the largest land animals in Earth's history.

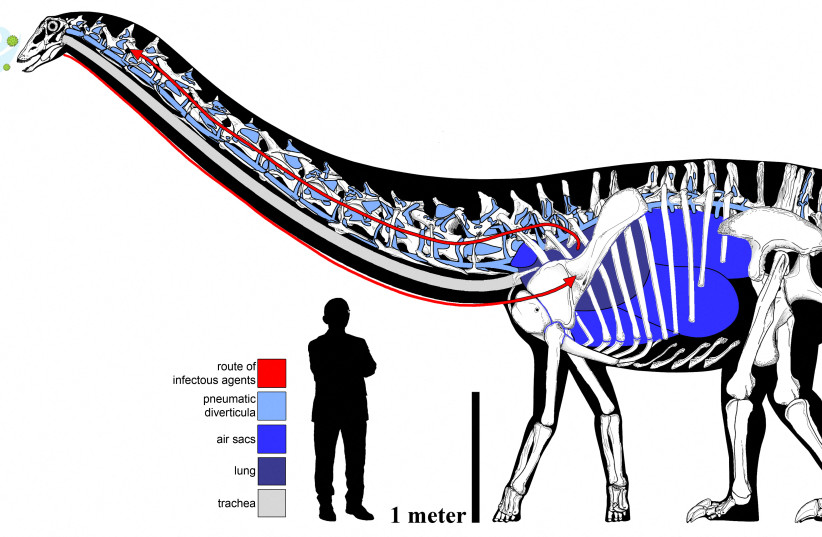

Dolly, about 60 feet (18 meters) long and weighing perhaps 4 to 5 tons, died at between 15 and 20 years of age, said Cary Woodruff, director of paleontology at the Great Plains Dinosaur Museum in Malta, Montana and lead author of the study published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Similar sauropods generally reached adulthood in their late 20s.

"Poor Dolly. She probably felt terrible with all the same signs and symptoms of a lower respiratory infection that we experience, such as fever, tightness in the chest, labored breathing, a productive cough - eew!" said anatomist and study co-author Lawrence Witmer of the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine.

"Was Dolly so sick that she couldn't keep up with the herd? Did she die from this disease? Did she die alone? We know that she was sick for a long time - it was a chronic disease - because she had it long enough for her bones to respond with nasty reactive bone growth," Witmer said.

It is not uncommon for sick animals to die not directly from disease but by falling victim to predation or starvation due to its debilitating effects.

"Yes, as scientists we're excited and intrigued by Dolly's disease, but as humans who love dinosaurs and another animals, our hearts break when we think about how the last days of this young dinosaur were spent ill, groggy, maybe surrounded by ferocious predators like Allosaurus," Witmer added.

Allosaurus fossils have been found in the same area.

Dolly's remains were unearthed in 1990 and 2013-2015. The scientific name of Dolly's species will be revealed in a future study. The dinosaur appears closely related to the well-known Diplodocus.

The researchers do not know Dolly's gender, but said the dinosaur was nicknamed after a famous singer.

"After Dolly Parton, of course," Woodruff said.

Dolly's dilemma not only sheds light on medical conditions in deep time but provides insight into the anatomical structure of dinosaur lungs and air sacs.

Sauropods and meat-eating dinosaurs called theropods, a group that includes birds, possess respiratory tracts far more elaborate than in mammals including people. In addition to lungs, they have thin, balloon-like air sacs that invade the body cavity and many bones. In Dolly, abnormal bone growths were present at the connection between respiratory tissue and bone in three vertebrae, evidence that the infection had spread from the lungs.

Aspergillosis, caused by inhaling spores from a fungus, is the most common respiratory infection today in birds, which evolved from feathered Jurassic theropods and are classified as a branch of dinosaurs.

"I don't personally know of any fossil I've been able to sympathetically relate to more," Woodruff said.